How to Develop Grit in an Art Museum

How to Develop Grit in an Art Museum

January 9, 2017 by Blanton Museum of Art

GRIT—a combination of passion and perseverance for a singularly important goal.

In Grit, an instant New York Times bestseller, pioneering psychologist Angela Duckworth shows anyone striving to succeed that the secret to outstanding achievement is not talent, but a special blend of passion and persistence she calls “grit.” Why do some succeed while others fail? Duckworth, a professor in the department of psychology at the University of Pennsylvania, has found that grit is the hallmark of high achievers in every domain. She has also found scientific evidence that grit can be developed throughout the lifespan.

With this new research in mind, the Blanton’s education team collaborated with partners in the College of Liberal Arts to design an experience in the museum that would provide freshmen, transitioning to college, with the opportunity to develop “grit”. Looking at works of art that depict people overcoming difficult situations – as seen in their actions, facial expressions, or physical stance – generates conversations about “grit”, but does not necessarily provide the feeling of experiencing a “gritty” situation.

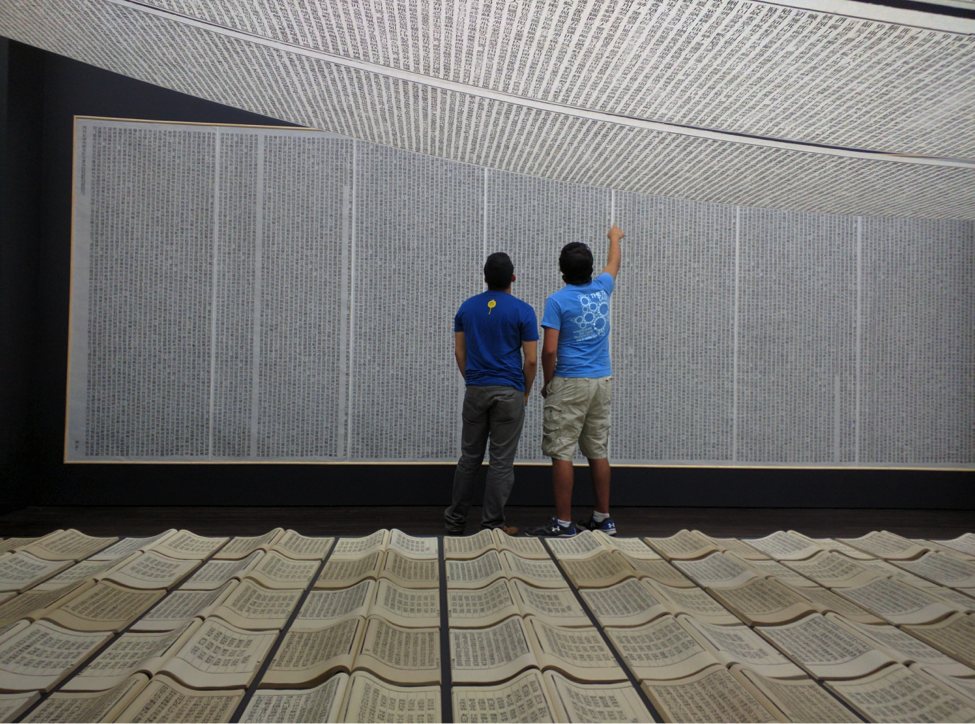

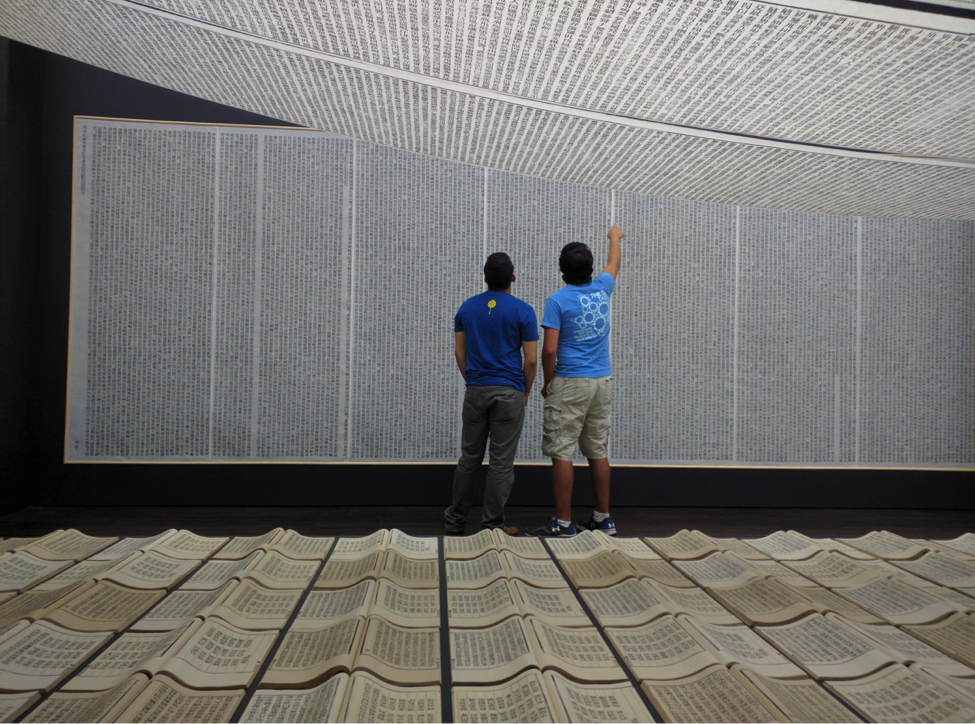

However, contemporary Chinese artist Xu Bing’s Book from the Sky has the hallmarks of grit written all over it. This is an installation consisting of an arrangement of books, scrolls, and large printed sheets of paper typeset from thousands of small wooden blocks, into each of which Xu Bing had carved an imaginary Chinese character – between three and four thousand invented characters in all. What could be a more appropriate catalyst for discussion and reflection than an artwork made out of books and language – things college students encounter and struggle with daily.

So our team came up with a simple equation to tackle the problem of practicing grit: combine a dollop of the artist’s passion and labor in creating Book from the Sky with the perseverance required of the student to make sense of a book that is essentially unreadable, stir together and create a gritty encounter.

But how could we make the activity of making sense of the work more intriguing? Students were teamed up in pairs, with each pair given a selection of handmade rice-paper discs showing Chinese characters. Unbeknown to the students, these characters had been taken from a catalogue essay on Xu Bing’s work consisting of authentic Chinese writing. The characters that they were trying to match up, although they looked authentic, were in fact thousands of made-up characters. Students were asked to spend 8 minutes carefully looking at the paper scrolls or wall panels or book pages in the installation and encouraged to match up their sample character with ones found in the artwork.

The task was daunting and overwhelming due to the sheer mass of characters and thousands of variabilities, not to mention the sheer impossibility of finding a match! Metaphors abounded: “it was like being in the Matrix” or “what it feels like to read academic texts” (remember they are freshman) or “how I feel being in college.” For other students, the activity was therapeutic and calming. Without fail, all students participated in the activity for the full 8 minutes (note: the average visitor spends 15 – 30 seconds in front of a work of art). When our groups reconvened after the matching experience, students reflected that although there were similarities between their sample characters and what was depicted in the work of art, nothing was a perfect match.

In their search for the match, however, other aspects of the artwork surfaced – the labor intensive process of printing on the wall panels and scrolls, curiosity about the content of the books and text, the sublime light and meditative space, the austere black and white relationships of both page and character, as well as paper and wall, the white negative spaces around the characters and how they became activated upon sustained scrutiny, the resemblance of the books to waves and the ocean, sky and clouds. When students were told that a match was impossible because of the made-up characters in Book from the Sky, the discussions exploded. The prevailing thought was why did we design an activity that had no achievable success? Some students compared the experience to what it is like grappling with academic texts, while others, if given a chance, would not have been deterred from completing the task until they found a successful match (these students would test high on the grit scale – yes, there is such a thing). Our conversations moved from ideas of labor, traditional and contemporary culture, disrupting habits of thinking, humorous gestures, historical empathy, reliability of knowledge, the futility of existence, questioning how we think, how language can be manipulated by those in power, the universality of rendering the reader illiterate, and the belief that deepest thoughts cannot be captured by words alone. And that became the point. Not completing a matching game, but deep and sustained conversation, thinking and feeling.

The point of the experience, to encourage sustained engagement with a work of art over time, was achieved. At the end of the lesson students were asked how many of them would have entered the installation space on their own and the duration of their looking. The answers varied from not at all to a few minutes. The matching activity encouraged perseverance over time for a goal. Not the goal they expected, but one ultimately more significant. A task that encouraged the development of “grit” in front of a work of art.

Siobhan McCusker is the Museum Educator for University Audiences at the Blanton.