The Work of Art That Edgardo Antonio Vigo Never Completed

The Work of Art That Edgardo Antonio Vigo Never Completed

July 27, 2018 by Penny Snyder

Studious visitors to the Paper Vault’s 2018 exhibition, From the Page to the Street: Latin American Conceptualism might notice a curious image tucked into an object label on the wall. A family of four stands in a row, backsides to the camera, wearing nothing but sheets of paper pinned to their backs. The sheets, barely legible, seem to be the ones framed on the wall. What are they doing on this family? Is this what the artist had in mind for his work?

The artist is Edgardo Antonio Vigo (1928–1997), a poet, printmaker, and pioneer of mail art based in provincial La Plata, Argentina. His art always took many forms: he made woodcuts and sculptures, sent collages through the mail, orchestrated ironic performances, wrote concrete poetry, and edited avant-garde magazines. He is well-represented in the Blanton’s collection, and selections of his mail art are on display in the museum’s Latin American galleries. Often, they are playfully presented in no particular order, encouraging the viewer to make her own connections and sort them according to her own logic.

Favoring a handmade, ephemeral aesthetic, Vigo made accessible work with simple materials and approached his work with irreverence, with the idea that everyone would receive and handle it differently, in a different order, building different connections and creating new meanings. All of his work is rooted in the idea that making art was a communicative and collaborative project.

La Plata, Argentina, 1928–1997

Obras (in)completas [(In)complete Works], from the portfolio De la figuración al arte de sistemas [From Figuration to Systems Art], 1970

Lithograph and letterpress on wove paper

Nettie Lee Benson Latin American Collection, University of Texas Libraries, The University of Texas at Austin

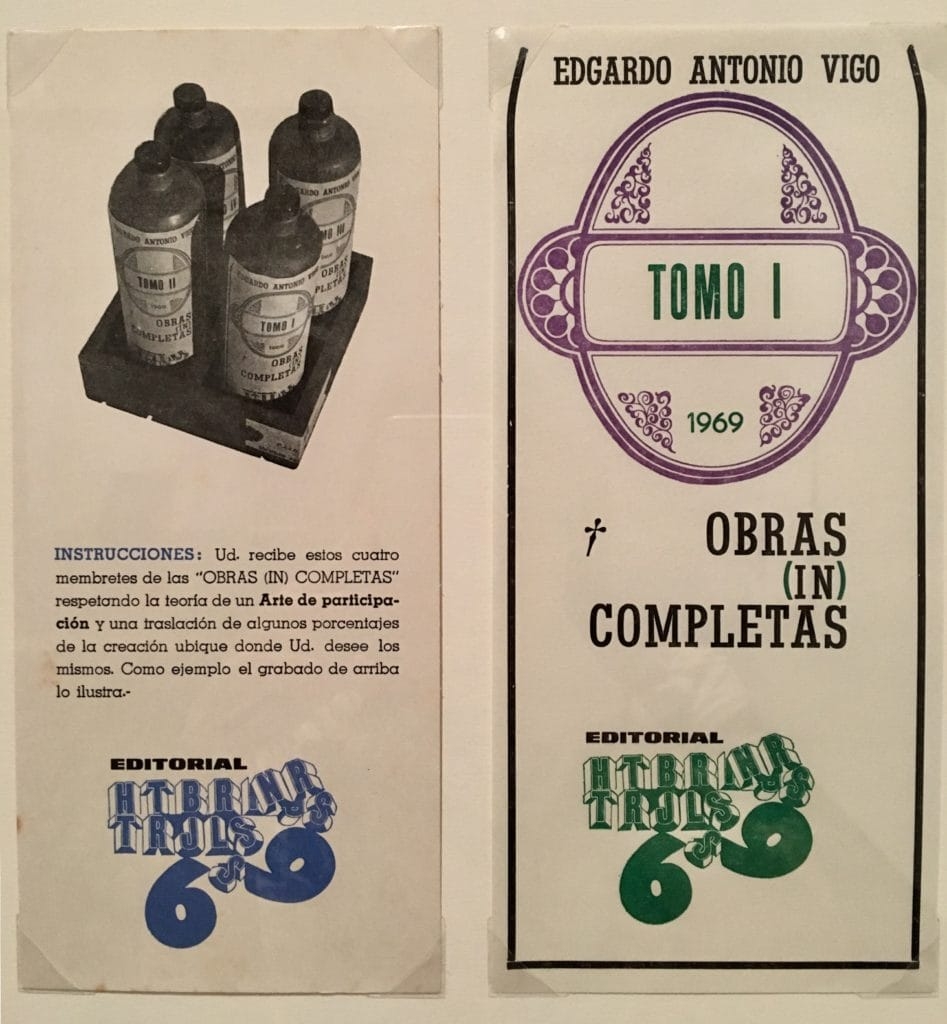

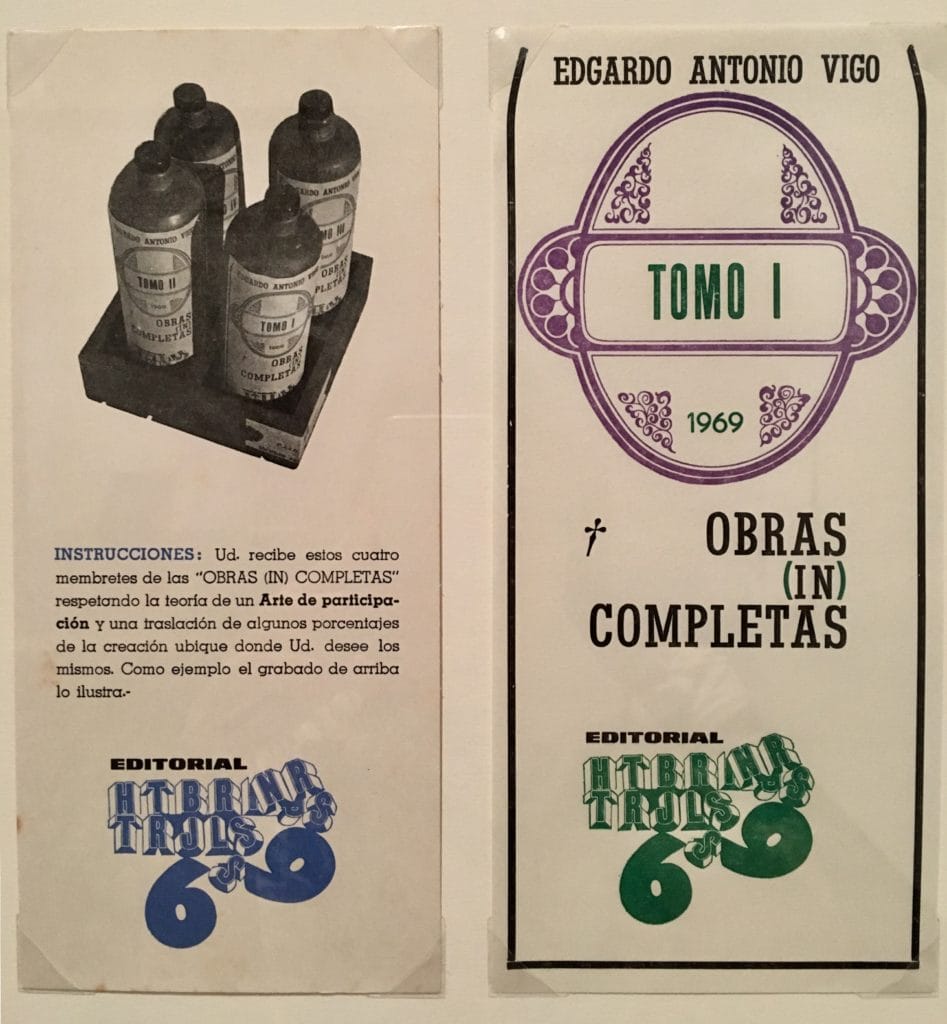

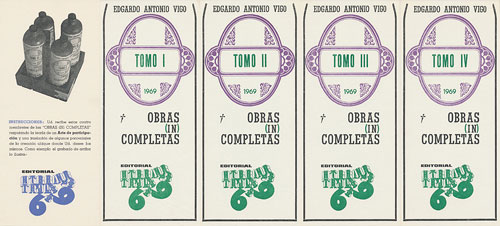

This work encapsulates many of the themes of Vigo’s prolific career. Titled Obras (in)completas [(In)complete Works], it is a series of four labels that might have arrived in the mail or tucked into the back of his magazine Diagonal Zero. They come with a set of instructions inviting recipients to affix the labels to anything they consider worthy of art status.

For example, following his own instructions, Vigo attached the labels to the earthenware bottles of Bols gin, often advertised as “the traditional drink of Argentine gauchos.” To the American writer Hugh Fox, Vigo explained, “YOU choose the object you want to turn into my incomplete works. I just happened to choose four bottles … they could just as well have been boxes or walls or anything else. … All I give are the labels. The rest is entirely up to you.” Vigo’s open-ended proposal for an incomplete work of art transforms the traditional role of a passive viewer into active participant in the completion of the work.

Last year, I had the opportunity to travel to Vigo’s home and archive in La Plata. There, I found a photograph of someone else’s response to Vigo’s proposal: the family that had attached the labels to themselves, turning their bodies into works of art. This cheeky response perfectly echoes Vigo’s playful experimentation with co-authorship while undermining the traditional relationships that objectify and commodify art objects. It also reverberates with the work of another Argentine artist, Alberto Greco. The first artist shown in From the Page to the Street, and in many ways a precursor to later works in the exhibition, Greco considered his own life a work of art, declaring, “Greco is a work by Greco.”

I see Vigo’s participatory art as open and generous, unified by a desire to connect people, to democratize the power structures of the art world, and to equalize the relationship between artist and viewer. Made during Argentina’s military dictatorships, this open-endedness was also a deeply political gesture, resisting the unidirectional flow of power under an authoritarian regime. Vigo’s work carries a salient political critique, but always with the wink – though it can be very poignant – of an outsider.

The Fluxus artist Ken Friedman once described Vigo as “an extraordinary human being and an important artist in a time that made extraordinary art difficult. Simply to function as a voice, simply to survive in his situation while remaining connected to the world outside, was heroic.”

Even now, Vigo’s work is radical. It asks us to reconsider our relationship to artworks. Does art have to be something that communicates a message to us, from inside a frame on the wall, or can we speak back to it, or even change it? Vigo offers alternative ways of interpreting art – by handling it, by sending it through the mail, by putting it on our bodies, or by making it part of our everyday life. Does something only become art once it is framed and hung in a museum, or sold in an art gallery, or can it become art whenever we say so?

From the Page to the Street, though it covers the 1960s-80s, poses questions that might still feel relevant to us today: How can art be used to critique systems of power (whether they are commercial or political)? How can art connect us to the outside world? How can art help us survive?

Julia Detchon is a PhD student in the Department of Art + Art History and the Mellon Curatorial Fellow in Latin American Art at the Blanton. She is the curator of From the Page to the Street: Latin American Conceptualism.