Women’s History Month 2020: #5WomenArtists from the Blanton Collection

Women’s History Month 2020: #5WomenArtists from the Blanton Collection

March 24, 2020 by Genevra Higginson

In a global environment adapting to the challenges presented by the Coronavirus (COVID-19), the Blanton stands in solidarity with her sister museums around the world. Together we recognize that art can offer a space for reflection and respite, but in these precarious times, we are strongest together by staying apart. Now is the time to #MuseumFromHome. During this moment, we invite you to join us as we explore our collection online. In honor of Women’s History Month, we would like to take this time to focus on women artists: their historic lack of representation in museum collections, their artistic voices, and the range of issues their art addresses today.

A 2019 study found that 87% of the artists in 18 major U.S. museums are male. Despite this continued imbalance, efforts are being made to transform the identity of the American art institution. Since 1985, the Guerrilla Girls have used their interventionist art to protest such inequality. For all of 2020, the centennial of women earning the right to vote in the U.S., the Baltimore Museum of Art announced that it will only purchase works by women. And, beginning in 2016, the National Museum of Women in the Arts (NWMA) committed to raising awareness about gender inequality every March during Women’s History Month. Using the hashtag #5WomenArtists, NWMA asks the question: “Can you name five women artists?” At the Blanton, we include the works by a diverse range of women to highlight the importance of female representation and empowerment. Check out our list below of five women artists from our print collection aiming to change the world through their art, including works that challenge views on representation, identity, immigration, and racial justice.

Artist: Barbara Jones-Hogu

Barbara Jones-Hogu, a painter and printmaker, helped found AFRICOBRA (African Commune of Bad Relevant Artists) in Chicago in 1968. The artist collective’s goal was to express the ideals of the Black Power Movement—namely, self-determination, unity, and black pride—via images. To do so, they developed an innovative style that mixed bold colors, flat forms, and rhythmic patterns. The result is an artistic vocabulary celebrating the heroic and beautiful qualities of black lives in America.

Trained across printmaking techniques including woodcut, etching, and lithography, Jones-Hogu gravitated towards screenprints for their ease of production and their ability to take on oil-based, colorful inks. In Nation Time, a dominant figure leads a black ensemble to rise up against the American flag background. Closer looking reveals that the American flag’s stars are Ku Klux Klan members. In this way, the composition acknowledges how racism is deeply embedded in America, while also inspiring hope of overcoming that truth. The Blanton’s impression of this work is printed on gold paper. Gold was a theme in Jones-Hogu’s prints, helping to symbolize the luminosity and inherent value of black lives. As Jones-Hogu explained in a 2011 interview, “In AFRICOBRA, we discussed positive ideas to portray our people. We wanted to make positive images in making statements, in directing and motivating them with particular thoughts, attitudes, and postures that we wanted to portray to the viewers.”

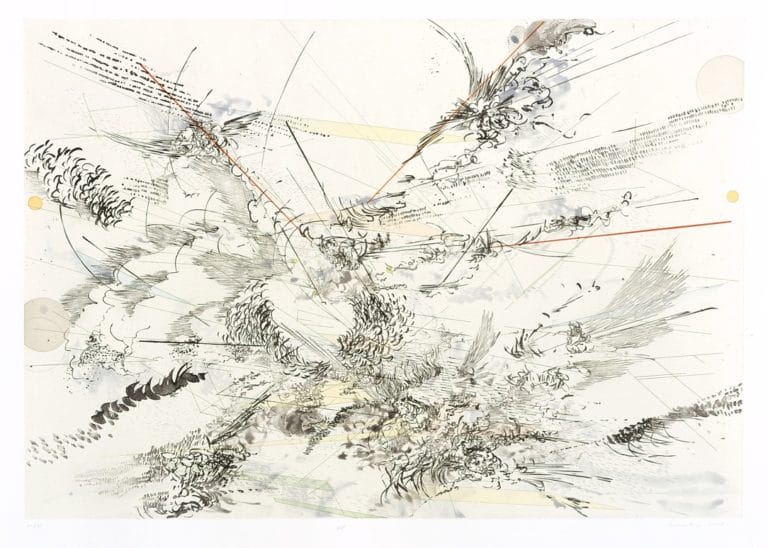

Artist: Julie Mehretu

Julie Mehretu was born in Ethiopia, emigrated with her family to Michigan, studied in Rhode Island and Senegal, and now lives in New York. Add to that itinerant life many artistic residencies around the globe, and it makes sense that Mehretu’s art explores society and culture. To engage with the idea of architecture as a framework for power constructs, Mehretu looks at maps, buildings, and human environments. Her work echoes those sources, and the results help us question how space can shape identity.

Mehretu has a very labor-intensive practice. Both her paintings and her prints involve creating a kind of geography through cumulative layering. After building up the surface of her canvas or paper, Mehretu can scratch away top layers to uncover individual images. In the Blanton’s print, Local Calm, lines scatter across the sheet, along with gashes of color and cloud-like assemblages. The title might be ironic, since its effect is a sense of chaos more than calm. As the Walker Art Center explains, “Mehretu’s art embodies the interconnected and complex character of a world that seems, at times, to be spinning out of control.” That feeling of disorder, or even dystopia, is integral to Mehretu’s work. She invites us to examine how unstable established structures can be, a call especially resonant in today’s political and environmental climates. In 2020, Mehretu had a mid-career retrospective co-organized by the Los Angeles County Museum of Art and the Whitney Museum of American Art.

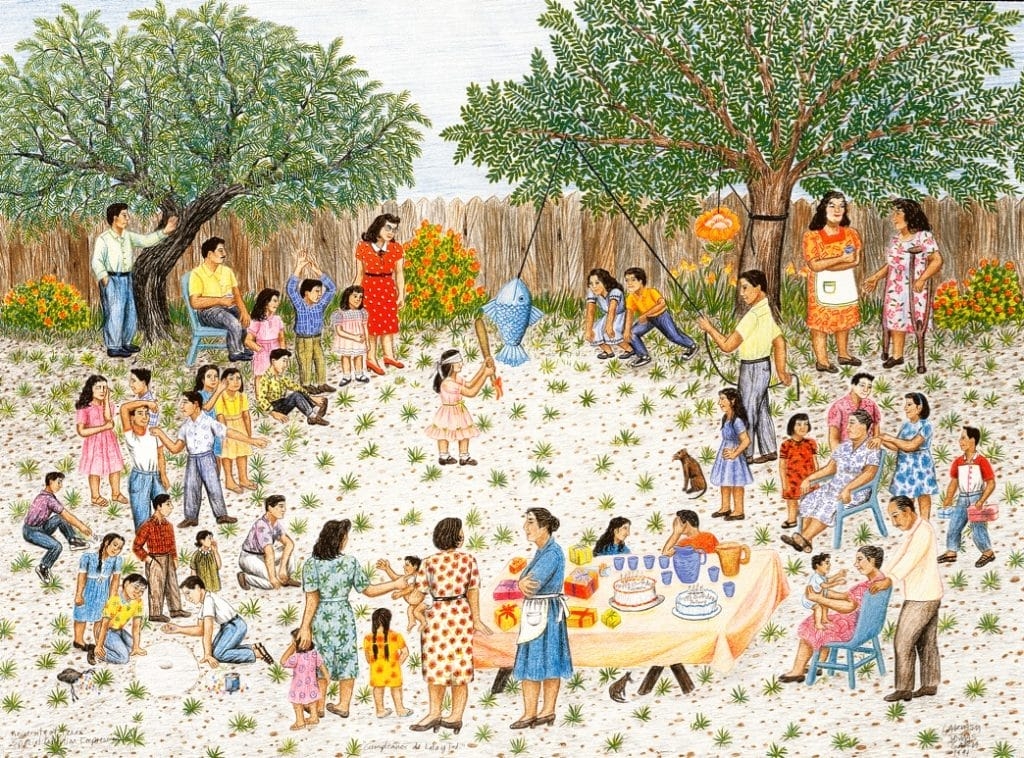

Artist: Carmen Lomas Garza

Born in Kingsville, Texas, Carmen Lomas Garza grew up in a small community near the Mexico-United States border. Watching her mother paint tablas (picture cards) and helping her grandmother make papel picado (cut, or “bitten,” paper) motivated Garza to become a visual artist. She was further influenced by the Chicano Movement in the late 1960s, which sought to represent the everyday lived experiences of Mexican Americans. Picking up on that ethos, Garza creates semi-autobiographical art ranging from paintings to prints to illustrated children’s books, all with images inspired by her childhood memories.

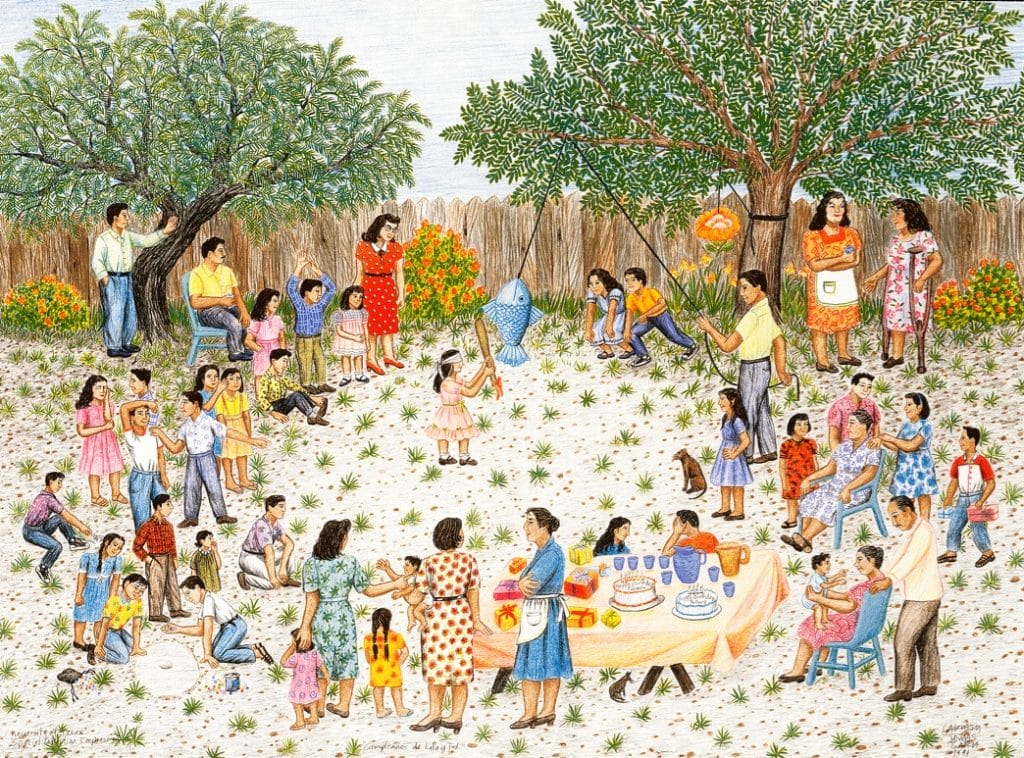

The Blanton’s print celebrates one such communal moment. In this masterful example of color lithography, family and friends gather at a birthday party. Babies squirm in mothers’ arms, children cast marbles on the periphery, and two elaborate piñatas hang enticingly from a tree—emblems of festivity as well as the legacy of cartonería (the Mexican art of making items from paper). Joy, humor, and a deep sense of connection radiate from each carefully observed detail. Other of Garza’s prints and drawings, as well as her personal papers, are housed in the Nettie Lee Benson Latin American Collection at the University of Texas at Austin in their Carmen Lomas Garza archive.

Artist: Natalia Goncharova

A leader of the Russian avant-garde, and a woman who challenged both social and gender conventions, Natalia Goncharova was a revolutionary artist. After spending her childhood in the Tula province of Russia in the 1880s, Goncharova studied for a time at the Moscow School of Painting, Sculpture, and Architecture. Because women were not officially awarded diplomas, Goncharova left and continued her training in the studios of other, more progressive painters. By combining European modernism with local folk art—drawing inspiration from traditional Russian sources such as textiles, carved wooden toys, and lubki (popular prints)—Goncharova produced unique art in such a wide range of media that her partner, the painter Mikhail Larionov, and the writer Ilia Zdanevich coined a term for her style: vschestvo (everythingism).

Although Goncharova’s work found acclaim among artistic circles, it also courted controversy. Upon exhibiting some of her paintings of female nudes in Moscow, Goncharova became the first modern artist to be charged with the production of “corrupting imagery” (despite her nudes not being any more revealing than those painted by men). Goncharova also painted religious icons, something that the Russian Orthodox Church had not sanctioned women to do. Further, Goncharova’s serene paintings of Jews challenged the ongoing pogroms carried out by the Tsarist government. Goncharova eventually moved to Paris, not only to work on costume and set designs, but perhaps also to find more artistic freedom. The Blanton’s print is Goncharova’s contribution to one of the Bauhaus print portfolios, which brought together artists who believed in the power of design to reshape modern life. Here, the single frontal torso resembles Russian icons, yet is a representation of a modern woman rather than a religious figure. Knit together with elemental shapes and primary colors, this woman could represent anyone enlightened enough to graft herself onto the bold figure. In this way, the print reflects Goncharova’s artistic ethos: to make art that satisfies not only her aesthetics, but also her conscience.

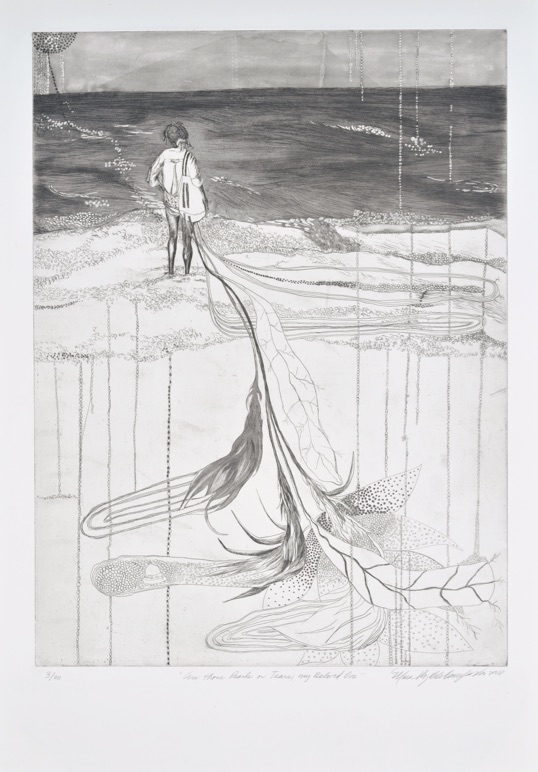

Artist: María Magdalena Campos-Pons

Women and the ocean are recurring elements in the work of María Magdalena Campos-Pons. Raised on a sugar plantation in Cuba, Campos-Pons has Nigerian, Hispanic, and Chinese heritage. Her Nigerian ancestors were brought to Cuba in the nineteenth century as enslaved people, and the trauma of that history—hers, as well as so many others’—is refracted in Campos-Pons’s multidisciplinary art. Of today’s immigrants and refugees, Campos-Pons has said, “Between Cuba and Miami, bodies float always… What kind of despair are people in when the embark on journeys so improbable?”

In the print Are Those Tears or Pearls, My Beloved One?, a young girl gazes out across a stretch of murky water. The frothiness of wavy whitecaps is depicted by individual bubbles, allowing an effervescence into the scene. We do not see the girl’s face, so the only visible tears (or pearls) are the strands that seem to rain from the sky: white droplets against dark water; black droplets against light sand. The girl has a bag slung over her shoulder, with ever-growing leaves and feathers descending down the shore. Thus, while she is tied to the land and its histories for now, there is hope she might take flight. Indeed, Campos-Pons infuses her work with the weight of the past and the promise of the future. “My credo,” she says, “is that we are more close than apart. To not understand that is an incredible failure of knowledge.”