by Nina Datz, 2022-23 Bridging Disciplines Program in Museum Studies Intern, Art of the Spanish Americas

As an art history student and museum studies intern, I recently had the opportunity to closely interact with a religious vestment known as chasuble currently on display in the Blanton exhibit Painted Cloth: Fashion and Ritual in Colonial Latin America. During the installation, I was fascinated by this object from Mexico City’s Museo Franz-Mayer: an astonishing, tangible piece of history. Like many of you reading this, my only experience in museums prior to my current internship was as a visitor. Getting the opportunity to be so up close and personal with an object that has this deep historical background was quite humbling. Who has seen, touched, and worn this piece before it entered a museum collection? What events has it been witness to? How did it survive all that history to end up here among the array of stunning artworks in Painted Cloth?

This heavily embroidered garment, most likely produced in Mexico or Puebla city around 1750, is a traditional priestly vestment known as a chasuble. Drawing its name from the Latin word “casula,” meaning small house/cottage, the chasuble is the main liturgical piece of cloth worn by priests officiating the Christian Mass. It is the most visible piece of a priest’s ensemble of clothing and is often richly ornamented with intricate embroidery, brilliant colors, and sumptuous materials.

Chasubles carry deep symbolism in Catholic ritual practice. Since the second century, they have been a staple component of liturgical wear. Over the years, they evolved as a result of changing accessibility to materials and style preferences. The medieval chasuble was a fairly simple, unpretentious garment that generally covered the arms of the wearer. By the Renaissance era, however, a growing preference for more ostentatious decoration made the garment too heavy for the wearers to raise their arms in prayer, leading to the sleeveless shape we can appreciate in the Franz Mayer piece. It was during the eighteenth century that chasubles were at their most richly decorated. Increased trade and colonial expansion resulted in greater accessibility to a wider variety of luxurious materials, like silver from the so-called New World and silk from Asia.

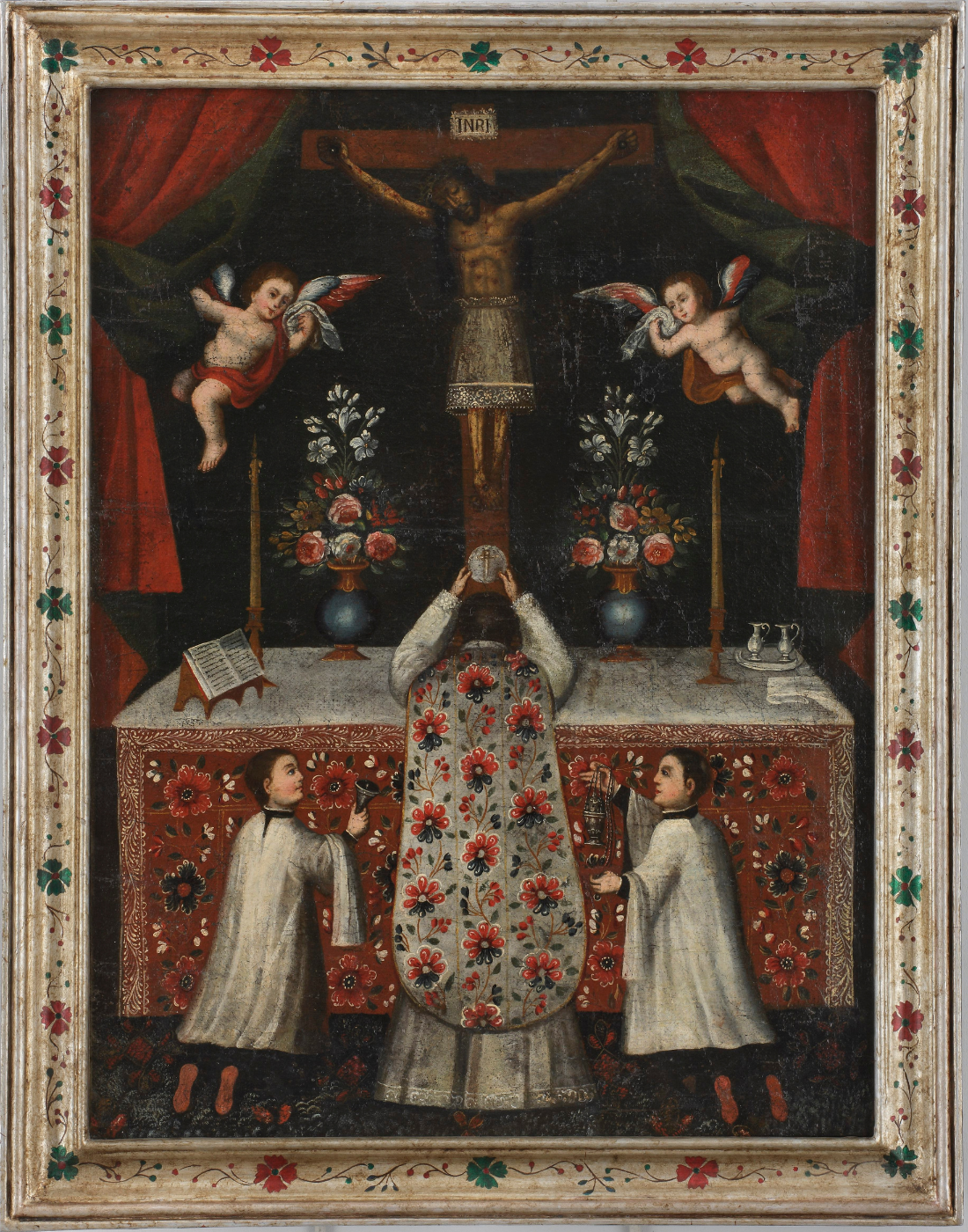

The symbolic weight of these garments is evident in the rite of priestly ordination, marked by the bestowal of the chasuble. This custom is alluded to in another artwork on view in Painted Cloth entitled Imposicion de la casulla a San Ildefonso [Imposition of the Chasuble on Saint Ildefonso], that Andrés de Islas painted in Mexico City in 1774. This painting depicts the moment when, according to legend, the Virgin Mary bestowed the chasuble upon Ildephonsus, Bishop of Toledo (657-667), in gratitude for his scholarly work. The chasuble has always been the central visual focus of those in attendance at Mass, making it worthwhile to dedicate significant amounts of effort and money to their creation. Adding to its ritual significance, the colors chosen for the chasuble and all other liturgical garments changed according to the liturgical calendar. Until 1969, when the Second Vatican Council determined that priests should always face their congregation during Mass, priests were positioned Ad orientum—facing away from the worshippers—thus privileging the altar itself during the transubstantiation ritual. This moment, when for believers the bread and wine become the body and blood of Jesus Christ, is depicted in a painting also in the exhibit, entitled Misa frente al Cristo de los Temblores [Mass in Front of the Christ of the Earthquakes], Cusco, 18th century.

The Franz Mayer piece is 210 centimeters long, entirely composed of silk, and ornamented with elaborate embroidery in shining gold and vibrant blue, green, and red silk threads. The front and back of the chasuble depict nearly identical compositions, representing a scene in which a golden vase in the lower center bursts with flowers as multicolored birds take flight around it. The design, while capturing an active and vivacious moment, has a distinct symmetry, with the two sides of the garment creating a mirror image of one another.

The use of color in the chasuble is worth significant attention. As previously discussed, color choices in Christian vestments were intentional and symbolic, based on the liturgical calendar. The dominance of gold in this chasuble suggests it was intended to be worn for feasts of the Lord, angels, and non-martyred saints, in addition to the feasts of Easter and Christmas. The variety of other colors that are used on the birds, leaves, and flowers evoke the natural world.

Beyond what we can observe by simply gazing at this beautiful chasuble through its display case, closer inspection during installation revealed to me the incredible technical skill of the textile workers who produced it, operating within an advanced system of textile production and drawing on thousands of years of developments across the globe. Metallic threads of gold and silver are present throughout the complex embroidery, allowing the garment to reflect the candlelight illuminating the church’s interior. This effect is the result of using hilos entorchados, twisted or braided thread in Spanish. In this technique, very thin ribbons of metal are wrapped around threads of silk. The metal ribbons can be of varying widths and wrapped more or less tightly around the silk thread, allowing for a slight variation in their visual effect. The appeal of the luminous effect created by this technique of wrapping threads in precious metals was widespread, and could already be observed as early as the 13th century in Europe, Byzantium, the Middle East, and Asia. Interestingly, it is also quite easy to fake entorchado threads, as the use of lesser-quality metals or common linen threads produces a result that is almost indistinguishable to the untrained eye from threads of genuine materials. Even with the naked eye, identifying these threads with the naked eye is rather difficult. During the day I was able to observe this chasuble from a very short distance. The entorchado threads did not really become clear until we placed a magnifying glass to the lens of a camera, which allowed Blanton staff to appreciate this complex technique. To see this close-up view for yourself, visit the Blanton’s Instagram page to see a video of some details.

The chasuble also highlights the importance of cultural interactions in shaping what constitutes ‘elite’ and ‘luxury’ styles across the globe. Textile traditions coming from Asia offered several options chosen by the creators of this chasuble. The primary material of the garment, for instance, is silk, which was produced solely in China for centuries until sericulture (silk production) spread outwards to the Byzantine Empire around the sixth century. Silk, as both a fabric and thread, quickly became a precious commodity favored by the elites of many cultures. This included the Christian Church, which denoted silk as a preferred material for liturgical garments. Additionally, the intricate embroidery on the chasuble reflects the impact of Asian textile traditions on those of Europe and the colonial world. During the colonial period, constant exchange between the Americas and the Philippines, both under the rule of the Spanish crown, facilitated the spread of ideas and goods from nearby Asian cultures to the Spanish Empire. Embroiderers in the Americas were especially drawn to Chinese fabrics, using them in their creations and taking inspiration from their frequent use of metallics and emphasis on botanical patterns and motifs.

Researching this chasuble and the history of the garment as a whole has been a fascinating experience in which I was able to actually answer many of the questions viewing objects in a museum often inspires me to ask. Having gotten the opportunity to work with historical textiles several times during my time as a student at The University of Texas, this incredible feeling of the weight of history and the hidden knowledge an object possesses is something that will never fail to leave me completely awestruck. I hope that when you visit this chasuble at Painted Cloth after reading this blog post, you consider the stories it tells.

Interested in learning about how conservators preserve 18th-century textiles such as this chasuble? Watch textile conservators Laura García Vedrenne and Mónica Solórzano Gonzales talk about preservation techniques for historic tapestries and costumes, and how textiles better our understanding of the colonial past.

References

An Unexpected Heritage Treasure: The Chasuble, Australian Catholic Liturgical Art. 24 December 2020.

Armella de Aspe, Virginia. Hilos del Cielo: Las Vestiduras Litúrgicas de la Catedral Metropolitana de México, Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia, Consejo Nacional para la Cultura y las Artes, 2007.

Stanfield-Mazzi, Maya. Catholic Cloth: Authority, Decorum, and Transcendence in the Spanish American Church. In Painted Cloth: Fashion and Ritual in Colonial Latin America, p. 159-175. The University of Texas Press, 2022.

Stanfield-Mazzi, Maya. Clothing the New World Church: Liturgical Textiles of Spanish America, 1520-1820. University of Notre Dame Press, 2021.

Thurston, Herbert. Chasuble, The Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 3. New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1908. 25 August. 2022.

Victorio Canovas, Emma Patricia. Seda y Oro para la Gloria de Dios: Los Ornamentos Litúrgicos de la Basílica Catedral de Lima, Museo de Arte Religioso de La Catedral de Lima, 2015.