Early 1990s

History

The Medellín Cartel detonates more than fifty bombs in Cali to damage properties of the local cartel. Cali’s progressive legacy of the 1970s is replaced by extreme violence, random social mobility, lack of urban planning, and general low morale. Through negotiations with the Colombian government, several armed groups agree to demobilize. These include the Popular Liberation Army (ELP), People’s Revolutionary Army (ERP), and the Movement April 19 (M-19). The nation is forced to offer Escobar and other cartel leaders protection from extradition and assistance in fighting sentences. Drug cartels continue to acquire land for the cultivation of coca and poppy, often through violent means. As a result, millions of farmers are displaced from their lands.

Art/Culture

Images of and information about violence proliferate in the media during the 1990s, slowly desensitizing the population.1 Violence becomes a ubiquitous presence in Colombian art, but artists seek new ways to address the complexity of issues. Doris Salcedo creates her piece Irritable, showing pairs of shoes in wall niches, each cubbyhole covered with translucent animal skin. The installation is based on her research into the effects of violence in Colombia. Murders of women were especially common and cruel; and victims were often identified by their shoes. Miguel Ángel Rojas begins to use coca leaves in his works as references to the drug trade. As violence pervades life in Cali, artists continue to work independently in their studios.

The Artist

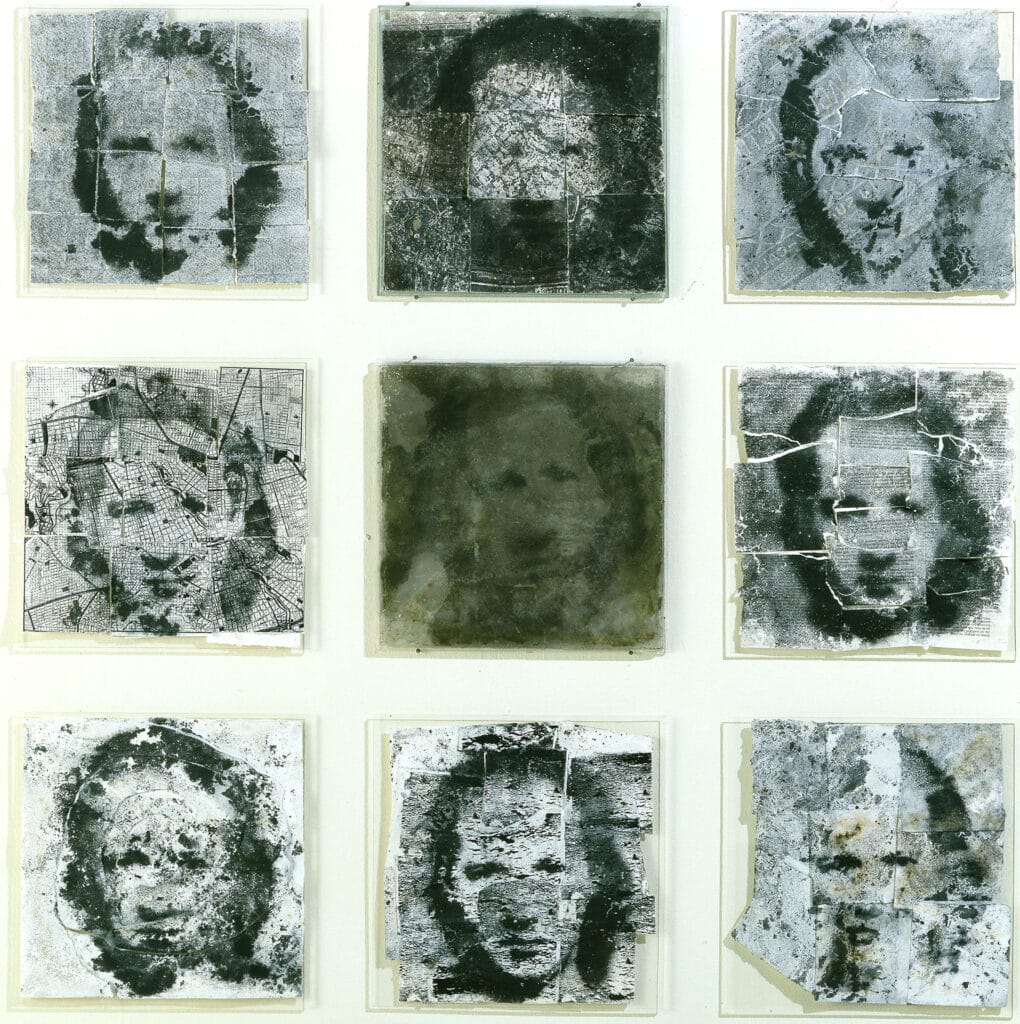

Muñoz slowly shifts the focus on his work during a period he sees as a creative crisis. He resolves it by privileging the process of production, which can last for days, over its results. He explores the dematerialization of art through methods such as pulverization and evaporation.2 “Most of my series are related to pulverized materials like charcoal, sugar, sand,” he explains. “I have had to go through many failures to reach some small achievements.”3 He continues to examine the effects of violence on society. He touches on themes such as the loss of personal and collective memory that obfuscate remembrance of the dead and disappeared. He addresses how violence becomes normalized as part of everyday life, perpetuating narratives of violence that exacerbate the problem.4

Muñoz begins his series Tainted, which is also the name of one of the new paramilitary groups that perpetrated one of the first massacres of civilians in the north of Colombia. Muñoz produces these pieces by depositing carbon dust on wet gesso on paper placed over a wood support in order to create complex textures. Based on newspaper photographs, these works depict bodies lying on tiled surfaces, ghostly shapes that dissolve into the dominant white. Muñoz makes a connection between pulverized carbon, dematerialized drawing, and violence.5 He explains, that “from the sensations I get from the photographs in the yellow press (which I collected for years), their frontal and ruthless illumination by flash, and the small indications and details of the ground that surround the corpse in these images, I worked on these drawings, also as surfaces that charcoal dust reveals, as scenes of a crime. Here the bodies become dematerialized in the intense luminosity, they melt into the surface, especially because in them I sought to make representation as an image yield to the intensity of sensation.”6 In the series Charcoal Surfaces, he uses wet gesso, paper, and charcoal, producing images that combine tile grids with dark smudges in order to suggest traces of human bodies.

1990

History

In February, a summit meeting takes place in Cartagena, Colombia, with President Barco Vargas and the presidents of the United States, Bolivia, and Peru, to coordinate an international war on drugs. In March, the guerilla groups M-19 and ELP sign a peace treaty with the Colombian government and demobilize. Liberal Party candidate César Gaviria is elected President of Colombia until 1994.

The Artist

Muñoz begins to exhibit the series Tainted and Charcoal Surfaces at the Museum of Modern Art La Tertulia; the Suramericana de Seguros gallery, Medellín; and the Garcés Velásquez Gallery, Bogotá.

1991

History

In July, the Colombian Constitutional Assembly passes a new Constitution that is supposedly more modern, democratic, and politically inclusive. Results are mixed as it weakens the autonomy of the Supreme Court. It allows undue influences and corruption that would eventually cause a judicial crisis. Colombian justice becomes one of the slowest systems in the world.

1992

Art/Culture

Muñoz participates in the exhibition America, Bride of the Sun: 500 Years, Latin America and the Low Countries, at the Koninklijk Museum voor Schone Kunsten Antwerpen, Belgium.

1993

Art/Culture

Miguel González organizes the exhibition Impulses at the Museum of Modern Art La Tertulia, including Alicia Barney, María Dolores Garcés, Elías Heim, Becky Mayer, Oscar Muñoz, Miguel Ángel Rojas, and Pablo Van Wong. In the catalogue, González writes about the local context, one of the few references to the effects of narco-terrorism in Colombia at the time: “A corrupt society—‘narcotized’ by easy money, and shameful for the climate and energy chaos that has resulted from a tradition of violating nature—is also capable of facing this drama and turning it into an artistic narrative. How those resources are persistently used in articulating associations, complaints, or simply pointing out situations, is the reason for this exhibition.”7 Muñoz participates in Impulses with his installation Atlantis.

The Artist

Muñoz works on Atlantis, an installation he calls an “experimental exercise.” It consists of a grid of nine shallow containers installed on the floor, filled with a thin layer of water and with sheets of paper floating on its surface. Using charcoal powder, he drew an image of the city of Cali on the paper. The artist becomes more critical of photographic documentation, remarking: “Never before had the visual image reached, thanks to technology, the precision and accuracy it has today. However, never before had its ability been questioned to show reality as it is. Today everything can be faked and we witness that without the same perplexity.”8Oscar Muñoz: Studies and Projects is presented at the Fine Arts Gallery, Cali.

Mid-1990s

History

Repeated anti-drug raids in the United States help force Cali Cartel’s trafficking operations from Colombia to Mexico via Panama. After Pablo Escobar’s death, the Medellín Cartel dissolves and the Cali Cartel takes over most of its operations, including drug production.

1994

History

Liberal Party candidate Ernesto Samper is elected President of Colombia until 1998. His administration is compromised when it is revealed that his campaign was financially supported by the Cali Cartel. To prove his innocence, Samper launches a sustained attack against the cartel’s leaders. President Samper’s government suffers important setbacks against the FARC (Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia), when this guerrilla group takes a record number of soldiers and officers of the Colombian Army prisoner.

Art/Culture

The exhibition The Color of Death in Cali includes Beatriz González’s One Swallow Doesn’t Make a Spring. The painting, about a massacre in the town of Segovia, shows the anguish of the victim’s family while surrounded by general indifference.9 Author Fernando Vallejo publishes The Virgin of the Assassins, drawing on his experiences with drug violence in Medellín. The book, a paradigmatic example of Colombian literature of this period, is later adapted into an internationally acclaimed film.

The Artist

Muñoz produces the floor installation Ambulatory (Walking Place / Outpatient Ward). According to the artist, it relates to “the so-called Cartel Wars, of the strong clashes between rival drug cartels and their shady partners in cities such as Cali and Medellín. From this period dates Ambulatorio [Ambulatory]… A huge aerial photograph of Cali (produced by the Instituto Agustín Codazzi, the same institution that makes the ground plans of the country) made from a sheet of security glass shattered into regular-shaped shards that correspond, on a small scale, to each building in the city. This piece, as its name suggests, is a large floor surface to be walked across. It evokes, moreover, the traces, the little that is left over at the end: in the days after the bomb has exploded… fragments of glass remain, like vestiges, incrusted in the pavement, practically unnoticeable until we come to step on them.”10

Muñoz also begins to work on his long series Narcissi, which were first produced to be exhibited at the Museum of Modern Art La Tertulia in Cali and is later shown in New York at the Ledisflam Gallery, as well as in Bogotá at the Garcés Velásquez gallery and then at the Museum of Modern Art. To produce this work, he creates a novel process of printing on water. It consists of sprinkling charcoal dust through a silkscreen mesh bearing his portrait, onto water in a shallow tray. The resulting image suspended on the liquid surface alludes to the classical myth of Narcissus. According to the artist, “the myth of Narcissus is that of representation par excellence, of looking at oneself as other and vice versa. This work, however, like much of my production, is also linked to the idea of memory.”11 In Dry Narcissi (part of the series), when the water evaporates it randomly deposits the carbon dust and imprints a distorted image onto a paper lining the bottom of the tray. In Muñoz’s words, “those three moments of the process in the Narcissi — when the dust touches the water and becomes an image, the process of change they undergo during the evaporation, and finally when the dust adheres to the bottom — suggest to me three definitive moments: creation, life and death.”12

1995

History

Between June and July, several of the heads of the Cali Cartel are arrested, including Gilberto Rodríguez Orejuela, alias “The Chess Player.”

Art/Culture

Filmmaker Luis Ospina airs his television documentary series Cali, Yesterday, Today, and Tomorrow, in which he explores the city’s cultural and social history, before he moves to Bogotá.13 Doris Salcedo begins to work on her Unland sculptures made of assembled table parts. The series addresses the disappearance of Colombians during the civil war.

The Artist

Muñoz begins to work on his interactive piece Breath. It consists of several oval mirrors screen-printed with grease and installed at eye level. The breath of the viewer on each mirror reveals portraits of the dead that come from newspaper obituaries, which the artist collects.

Muñoz explains how the piece functions: “In Breath, inhalation and exhalation occur. When you exhale the image of the other appears and your image disappears from the mirror. You cannot sustain this other image. When you are exhaling, you need to inhale, and the moment you do so, the image of the other disappears and yours appears… In this artwork there is a dialogue between the life of the other and that of the spectator. A very close relationship on a vital and visual level…. Watching how the image of the other is unmade, how it is lost and how we cannot sustain it, can be painful; but, at the same time, comforting for the viewer to see their face appear again. It’s like when you say, ‘Finally, I can breathe again!’”14

1996

History

Opposition from Samper’s government and cartel infighting result in the apprehension or death of most of the Cali Cartel leadership by the end of 1996. The Norte del Valle Cartel takes over operations in Cali.

Art/Culture

The V Bogotá Art Biennial takes place at the Museum of Modern Art of Bogotá (MAMBO). It features several works addressing violence and widespread corruption. These include Muñoz’s installation Breath, and Juan Fernando Herrán’s pieces Fuchsia Boxes with Bright Stars and Annex 273. Herran’s works are among the first to focus on the Cali Cartel’s corruption of the government of President Samper and his Minister of Defense Fernando Botero Zea, son of famous Colombian artist Fernando Botero and Gloria Zea, MAMBO’s director.15 Miguel Ángel Rojas creates his installation Broadway, featuring a path of coca leaves that trail across a wall as if they were carried by ants.

1997

History

From 1997 to 2006, many right-wing, counter-insurgent, drug-trafficking paramilitary groups come together as the United Self-Defense Forces of Colombia or AUC. In their attacks against the FARC and ELN (National Liberation Army), they commit a series of massacres. Approximately 80 percent of civilian murders during this period has been attributed to the AUC.16 The Ministry of Culture is created in Colombia with the mission to preserve, promote, and encourage the growth, free expression, and understanding of the culture of Colombia in all its multicultural forms.

Art/Culture

Muñoz’s work is included in the show Re-aligning Vision: Alternative Currents in South American Drawing, a traveling exhibition organized by the Archer M. Huntington Art Gallery, Austin, Texas, with venues in New York, Caracas, Monterrey, and Miami. He participates in the International Art Festival, Lima; and the 6ª Havana Biennial, Cuba, with his piece Breath.

The Artist

Muñoz has solo shows at Barcelona’s Metropolitan Gallery and Pereira’s Museum of Art.

Late 1990s

History

Cali is believed to have about fifty organized operations of sicarios (assassins for hire) conducting business behind the façades of legal enterprises such as beauty salons and car dealerships.17 FARC guerrilla groups begin a criminal practice called “miracle fishing” that involves mass kidnappings of random people. The guerrillas suddenly block traffic in routes connecting cities around the country, then take hostages and their property. The victims are evaluated by the kidnappers according to their political or economic value, or assassinated. The practice, which brings FARC a large amount of money, terrorizes the population.

1998

History

Conservative Party candidate Andrés Pastrana is elected President of Colombia until 2002. During his mandate, unemployment and economic instability increase tensions in the Colombian civil war. The FARC and ELN participate in the peace process that President Pastrana initiates but do not agree to a ceasefire and strong attacks persist. Drug production increases, as do corruption and paramilitary groups. It is estimated that hundreds of massacres (defined as the murder of three or more people) took place in Colombia during the late 1990s, leaving thousands of people dead.18 Pastrana conceives the Plan Colombia as a kind of “Marshall Plan” for his country involving investments in social programs and helping farmers grow crops other than coca. In November, Pastrana declares an area in southeastern Colombia a safe haven for FARC combatants in order to move the peace process forward.

Art/Culture

Colombian artist Fernando Botero donates a large art collection, including two hundred of his own works and eighty-seven works by other international artists, to the newly created Botero Museum of the Bank of the Republic in Bogotá. He also donates one hundred of his own works and sixty pieces by international artists to the Museum of Antioquia in Medellín. The art collective Helena Producciones is founded in Cali to promote research, exhibitions, television projects, publications, and workshops. They undertake the organization of the Cali Performance Festival, which is held eight times, between 1998 and 2012. The group includes founder Leonardo Herrera, as well as Alberto Campuzano, Wilson Díaz, Marcela Gómez, Diana Lasso, Johanna Martínez, Juan David Medina, Juan Carlos Melo, Ana María Millán, Ernesto Ordóñez, Gustavo Racines, Andrés Sandoval Alba, Claudia Patricia Sarria-Macías, Giovanni Vargas, and Mauricio Vera. The exhibition Amnesia: New Art from South America, with venues in Los Angeles, Cincinnati, Bogotá, Tampa, and New York, includes Muñoz’s work.

1999

History

Plan Colombia evolves into a treaty between Colombia and the United States to combat drug cartels and left-wing insurgent groups. From 1999 to 2015, the Plan involves US funding and training Colombian military and paramilitary forces, as well as selling fumigation services to eradicate illicit plantings. The Plan has mixed results with small reductions of the coca cultivation areas, but ongoing drug traffic to the United States continues. Cartels infiltrate US personnel involved in these operations, thus increasing the level of corruption.

Art/Culture

The Museum of Modern Art of Bogotá presents the exhibition Art and Violence in Colombia since 1948, which includes the work of Muñoz. The Colombian soap opera Ugly Betty becomes a huge television hit. The script is sold to different producers in different countries, and the show becomes an international success.

The Artist

Muñoz makes his work Pixels with sugar cubes tinted with coffee, as if they were a pixelated image of a face that is best seen from a distance. Coffee and sugar were among Colombia’s chief exports until drugs displaced them in the 1980s. In his new piece Simulacra, Muñoz modifies the format of Narcissi. He silkscreens three images (in this case, of his charcoal drawings depicting different parts of his body) on the surface of water with carbon dust. The liquid is contained in three trays that are carefully lit. Every fifty seconds, a pump releases a drop of water onto each tray, altering the image.19 Muñoz stated that for him the work is “a metaphor of the body as a fragile container of vital liquid: the drop falls, shaking everything up, and creating new images that are destroyed every 50 seconds.”20 The show Oscar Muñoz is presented at the Throckmorton Fine Art gallery in New York, while Oscar Muñoz. Narcissi. Breath, takes place at the MEC Center, Ministry of Education and Culture, Montevideo, Uruguay.

1 María Margarita Malagón, “Art as Indexical Presence, The Work of Three Colombian Artists in Times of Violence: Beatriz González, Oscar Muñoz and Doris Salcedo in the 1990s,” doctoral dissertation, The University of Texas at Austin, 2006, 70.

2 Diego Garzón, Otras voces, otro arte: diez conversaciones con artistas colombianos (Bogotá: Planeta, 2005), 49.

3 María Wills, “Entrevista retrospectiva a Oscar Muñoz,” banrepcultural.org <https://www.banrepcultural.org/oscar-munoz/entrevista-memorias-infancia-juventud.html>, accessed January 28, 2020.

4 Garzón, Otras voces, otro arte, 49.

5 Wills, “Entrevista retrospectiva”; Maria Iovino, Oscar Muñoz: volverse aire (Bogotá: Eco, 2003), 44-45; Miguel González, Oscar Muñoz (Bogotá, Museum of Modern Art, 1996), 28.

6 Muñoz, cited in González, Oscar Muñoz (1996), 28.

7 Miguel González, Pulsiones (Cali: Museo de Arte Moderno La Tertulia, 1993).

8 Muñoz, cited in Malagón, “Art as Indexical Presence,” 158.

9 Malagón, “Art as Indexical Presence,” 104-106.

10 Oscar Muñoz, “Talk given at Global Photography Now, Tate Modern,” in Carlos Jiménez, et al., Óscar Muñoz: Documentos de la amnesia (Badajoz: Museo Extremeño e Iberoamericano de Arte Contemporáneo, 2008), 202-203.

11 Muñoz, cited in Garzón, Otras voces, otro arte, 59.

12 Muñoz, cited in Garzón, Otras voces, otro arte, 48.

13 Marie-Françoise Govin, “Luis ¿por qué Cali?” cinémas d’amérique latine, no. 25, 2017: 22-33. Digital Object Identifier (DOI): <https://doi.org/10.4000/cinelatino.3568>. Accessed on September 15, 2020.

14 Muñoz, cited in Garzón, Otras voces, otro arte, 61.

15 Santiago Rueda Fajardo, Una línea de polvo: Arte y drogas en Colombia (Bogotá: Alcaldía Mayor de Bogotá, 2009), 52–54.

16 Daniela Castro, “El rastro de la muerte: 30 años de masacres en Colombia,” InSightCrime.org, May 8, 2014; accessed June 17, 2020.

17 Alexander Castillo Garcés and Ana María Betancourt Ledezma, “Violencia y políticas de seguridad en la ciudad de Cali–Colombia,” Summa Iuris, vol. 5, no. 2, July–December, 2017: 300. Digital Object Identifier (DOI): <https://doi.org/10.21501/23394536.2598>.

18 Gonzalo Sánchez Gómez, “Guerra prolongada y negociaciones inciertas en Colombia,” in Violencia y estrategias colectivas en la región andina: Bolivia, Colombia, Ecuador, Perú y Venezuela (Lima: Institut français d’études andines, 2004), 52.

19 Iovino, Oscar Muñoz, 56.

20 Muñoz, cited in Garzón, Otras voces, otro arte, 64.