A Life in Tablets: Eleanore Mikus

A Life in Tablets: Eleanore Mikus

September 25, 2017 by Veronica Roberts, Former Curator of Modern and Contemporary Art, Blanton Museum of Art

When I arrived at the Blanton more than four years ago, I was instantly drawn to a painting from the late 1960s by Eleanore Mikus that was on view in the museum’s galleries. Although I was unfamiliar with Mikus’ work at the time, I have since come to consider her painting to be one of the treasures of the Blanton’s collection. It is currently on view and keeping excellent company with works by Agnes Martin, Brice Marden, and Louise Nevelson.

This May, Kara Carmack, a doctoral candidate and our recent Mellon Fellow in the Modern and Contemporary Art department, flew to New York to interview Mikus in what was likely the last significant interview of the artist’s 90-year-life. Below is Kara’s tribute to Eleanore Mikus—written before Mikus died in her home on September 6th, 2017—and links to excerpts from their lively conversation.

– Veronica Roberts, Former Curator of Modern and Contemporary Art, Blanton Museum of Art.

Eleanore Mikus (1927–2017)

When I first met artist Eleanore Mikus, she was sitting in her cozy library with a just-read copy of Ernest Hemingway’s The Old Man and the Sea still in her hands. The library, sequestered from her large, open live-work space by dark wooden bookshelves, brims with art books, fiction, and films (her favorites being Westerns for their predictability). After introducing myself and taking a seat for a few minutes before our formal interview began, I had momentarily forgotten that I was inside of an 1823 church.

Situated about seventeen miles northeast of Ithaca, New York, where Mikus taught at Cornell University, and several miles outside of the quaint village of Groton, Mikus’ studio is curiously similar to what her New York City SoHo loft might have looked like in the 1960s: large, bright windows; an uneven ancient wood floor; unfinished elements, such as the open ceiling and its impressive raw beams; and the exposed sleeping lofts and bookshelves that soar above the congregation of bookcases, tables, chairs, and flat files, along with a remarkable array of work spanning her more than sixty-year career hanging on nearly every vertical surface available.

Born in Detroit, Michigan, in 1927 to Joseph Mikus, a precision toolmaker, and Bertha Englot, a surgical garment designer, Mikus gravitated toward art at a young age, winning first prize in a kindergarten art contest for her rendering of a farm despite never having seen one in person. She recalls her family not being particularly affected by the Great Depression at the time, and the white blouses and blue skirts of her parochial school uniform seem to have left an impression. After studying painting at Michigan State in the late 1940s, a summer spent in Mexico learning the time-consuming techniques of lacquer painting, and a few years taken with traveling throughout Europe, Mikus graduated from the University of Denver in 1957, receiving a BA in painting and art history. Her paintings from the 1940s and 1950s reveal affinities with Arthur Dove’s swirling, unsettled landscapes, but also show an increasing awareness of Abstract Expressionism on the rise in New York at the time.

A turning point in her artistic development came in 1960 when Mikus moved within New York to a studio at 76 Jefferson Street on the Lower East Side from where she could see the East River. It was in that raw, illegally occupied studio (she recalls hiding from the fire department) that she began her innovative experimentation with a wide variety of materials: rabbit-skin glue, stamp hinges, loose-leaf reinforcements, ring binders, cloth and rubber bands, grooved plywood, and nails.

Mikus’ use of found materials can be understood within a broader context of other artists at the time taking advantage of the city’s abundant discarded materials, such as Jim Dine, Robert Rauschenberg, and her friend Louise Nevelson. Mikus told me a tale of a particularly memorable object she coveted for one of her works, her aching fondness for it still evident in her voice and demeanor:

“I remember once there was a beautiful piece of wood I needed for framing and back. It was about ½ by ½ inch square—it was a long stick in a barrel. I was headed for it. It was close to the lumberyard. Someone must’ve thrown it out or it fell on the ground and this kid came and he took it out; he was in front of me. He took it out of the barrel and I walked behind him waiting for him to throw it away. He never did. He got his stick and I followed him. Wood was expensive. Everything was expensive to do.”

Within a year, Mikus turned her attention to developing a series of monochromatic paintings she called “Tablets,” experimenting variously with wood, canvas, and fiberglass, that would preoccupy her throughout the 1960s and again in the 1980s. Unlike the refined finishes of her Minimalist contemporaries, Mikus embraced a process-based, handmade aesthetic receptive to the elements of chance. To create these vigorously demanding works, she turned her uneven floor (now on Broome Street in what was then called “Hell’s Hundred Acres” and coincidentally in the same building as James Rosenquist and Robert Grosvenor) into her easel, building the paintings from the reverse by assembling an irregular base of plywood or Masonite and gluing the braces onto the back. Mikus then raised the piece from the floor, sometimes ripping it up because of the glue, to see the front with all its attendant holes, dents, and concave and convex forms for the first time. After sanding and beveling the edges and applying several layers of gesso, she would begin the laborious process of applying a coat of paint and then sanding it away. As she described the process to me:

“Whatever you put on you took off. And then I put some more on and then sanded that. Built up a patina. If you smudged it you just couldn’t paint over that one area because it would be different than the other area. You had to include it and start all over.”

She repeated the practice until she felt the work had achieved what she describes as “substance, feelings.” Taking anywhere from two weeks to six months, she affirms, “I have to have feelings in there. Something has to say something. If it doesn’t say it, then to me, it’s not finished.”

1967-1968

131.4 cm x 76.2 cm x 5 cm (51 3/4 in. x 30 in. x 1 15/16 in.)

Epoxy resin on fiberglass

Gift of Gabrielle Burns, courtesy the Artist and Mitchell Algus Gallery, 2004

A close look at Mikus’ Tablet 164, 1967–68, presently on view in the Blanton’s collection galleries, reveals the highly refined, luminescent surface realized by Mikus’ labor. The three-dimensional relief is smooth, as though it has been worn down by centuries of erosion—a patina that she has likened to that of a subway turnstile touched by thousands of hands. Topographical ridges undulate across the surface, drawing in real time and space with real light and shadow. Without the distraction of color, the purity and serenity of the monochromatic white emphasizes the ever-changing shadows cast by the rippling, active surface. An impossible chiaroscuro in white.

As the title suggests, the surface seems to be a notational record, or trace, of Mikus’ efforts:

“You put the painting in there. You created the structure, and you actually created the way to do it. It’s not just a canvas. You were creating it the moment it hit the floor. You put it together. You made decisions all along…. And you have something that’s like the movements in your own life.”

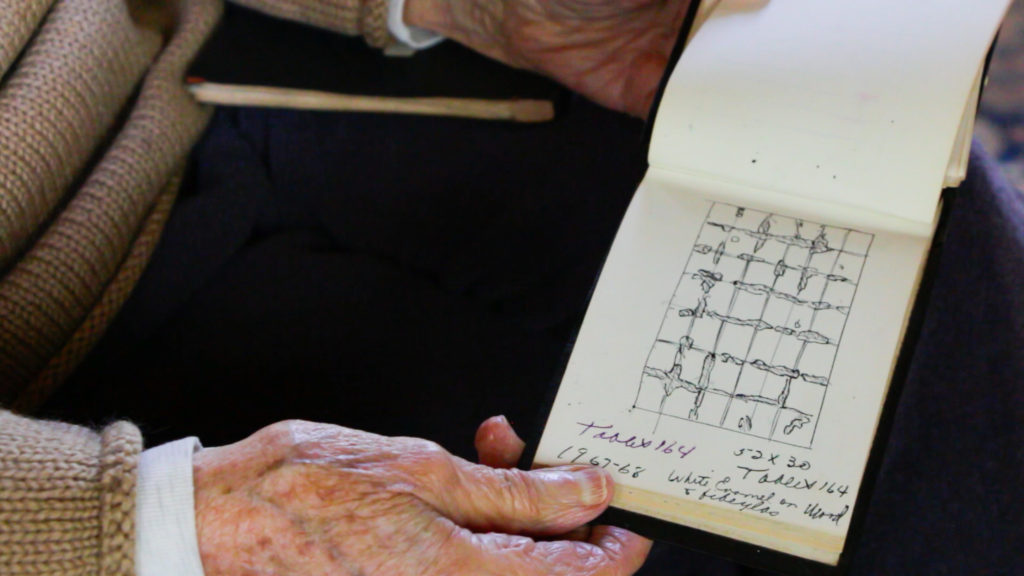

Once complete, Mikus recorded each Tablet in a notebook with a drawing because to capture their precise surfaces and compositions in photographs was nearly impossible.

Untitled

2007

49.5 cm x 147.3 cm (19 1/2 in. x 58 in.)

White hand folded paper

Purchase through the generosity of Houston Endowment, Inc. in honor of Melissa Jones, 2008

In 1963, Mikus showed her Tablets for the first time at Pace Gallery, Boston, and it was for that show that she made her first paperfold in the form of the exhibition flyer. In her paperfolds, she variously folds, presses, or irons creases into paper to produce lines within the surface, an outcome not unlike her Tablets. This repetitive process converts paper, a traditional support of drawing, into the drawing itself. In the Blanton’s Untitled, 2007, a white paperfold over three feet long, the heat from the iron used to press the vertical and horizontal folds released moisture from within the paper, bringing forth irregular, circular formations to the surface that interrupt the accumulating grid modules formed by the lines. The subtle, restrained traces of Mikus’ working method encourage a serene, Zen-like meditative viewing experience.

As our afternoon together carried on, our conversation touched upon her other bodies of work that collectively demonstrate Mikus’ persistent interrogation of medium-specificity and form. In 1968, she completed an impressive total of 32 print editions as a fellow at the Tamarind Lithography Workshop, Los Angeles, during which she had paradoxically hoped to create a print without ink. Her brief foray into neo-expressionist painting followed that exhausting yet productive residency, nearly a decade before such a style took hold in New York. Though these large, representational and colorful canvases seem anomalous in a career defined by abstraction, they retain conceptual ties to the notational underpinnings of the Tablets in their employment of another form of communication—the pictogram. Mikus soon returned to making Tablets and paperfolds, but this time incorporating color into her ongoing investigations of light, shadow, line, composition, and temporality.

Before my departure, Mikus showed me her latest series of paintings, which mark her return to the white monochrome. Combining elements of her paperfolds with her Tablets, these works push further still against the limits of drawing, painting, and relief. Though they are much more modest in size compared to her considerable Tablets of the 1960s, she nevertheless declared as she handled the unfinished works, “I need a bigger studio.”

Written by Kara Carmack

2016–17 Andrew W. Mellon Fellow for Modern and Contemporary Art, Blanton Museum of Art