Austin In Depth

CHAPTER 2: Kelly’s French Foundations: 1948–5

Chapters

Born in Newburgh, New York, and raised in New Jersey, Ellsworth Kelly displayed artistic talent and an exceptionally keen sense of observation as a boy and adolescent. As with many young men of his generation, his life was influenced by the global upheaval of World War II and the social transformations and opportunities it created. Before the war, the artist studied at the Pratt Institute in Brooklyn, New York, but with its outbreak, he enlisted in the army and was sent to France in 1944. He served in the 603rd Engineer Camouflage Battalion, creating, among other things, instructional posters (figure 1) and, more importantly, fake army battalions deployed to fool the enemy (figure 2). An early sketchbook from this period shows his interest in ecclesiastical architecture (figure 3) and is filled with other drawings, such as fellow soldiers relaxing and resting (figure 4). This early work shows technical skill and a love of drawing if not full artistic maturity. Kelly’s company was stationed near Paris in November of 1944 and he visited the city for the first time then, well aware of its status as a cultural capital. France and its culture would have a deep and lasting impact.

When the war ended, the young artist qualified for the GI Bill and used it to study at the Boston Museum School; he was still working in a somewhat traditional vein but was also influenced by German Expressionism and Pablo Picasso (figure 5). Always an assiduous student of art history, Kelly studied medieval frescoes and early Italian Renaissance paintings on view in Boston museums; such works would impact him more than European modernism or contemporary art. He decided to return to Paris, planning carefully and recording the places and art he wished to see in a small notebook, still in his studio archive, with checkmarks indicating a completed visit (figure 6).

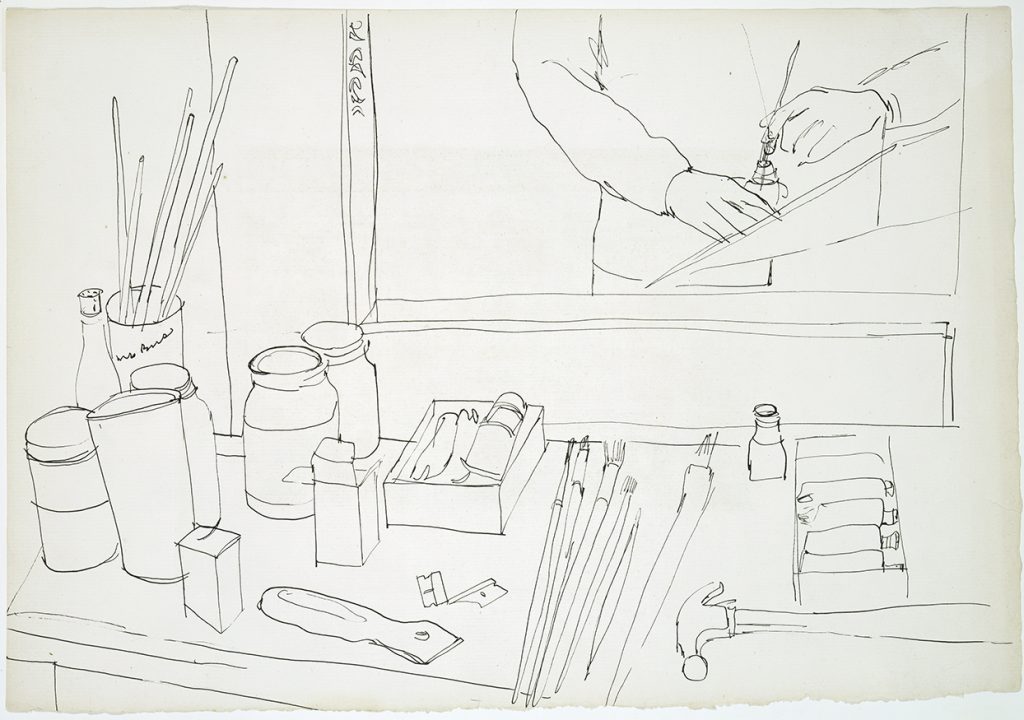

Kelly’s time in France would prove transformative for his art. For the next several years, he frequently traveled around the country and elsewhere in Europe, took a series of odd jobs to support himself, and forged important artistic and social relationships that fed his creative ambitions. The drawing Hôtel Saint-Georges, Paris (Self-portrait) from 1948 shows the first place he settled and reflects his compulsion to work, showing the tools of his trade, including his hands reflected in a mirror (figure 7). Kelly often traveled with his close friend and fellow artist Ralph Coburn (figure 8) and was able to meet and in some cases form friendships with more established figures, including Constantin Brancusi, Hans Arp, Georges Vantongerloo, Alexander Calder, John Cage, and Merce Cunningham.

The artist himself described the creative breakthrough he had in France in this often cited quotation:

In October of 1949 at the Museum of Modern Art in Paris I noticed the large windows between the paintings interested me more than the art exhibited. I made a drawing of the window and later in my studio I made what I considered my first object, Window, Museum of Modern Art, Paris. From then on, painting as I had known it was finished for me. The new works were to be paintings/objects, unsigned, anonymous. Everywhere I looked, everything I saw became something to be made, and it had to be made exactly as it was, with nothing added. It was a new freedom; there was no longer the need to compose. The subject was there already made, and I could take from everything; it all belonged to me: a glass roof of a factory with its broken and patched panes, lines of a roadmap, the shape of a scarf on a woman’s head, a fragment of Le Corbusier’s Swiss Pavilion, a corner of a Braque painting, paper fragments in the street. It was all the same, anything goes.[1] (figure 9)

Art historian Yve-Alain Bois has helped define Kelly’s artistic achievement during this crucial moment, using the term non-composition to refer to the artist’s interest in removing himself from the act of decision-making and composing. Bois has articulated four strategies Kelly adopted in his non-compositional mode of making: chance, transfer (the recording of a flat pattern on a flat support), the modular grid, and the monochrome panel.[2] And although Kelly is generally regarded as an abstract artist, one crucial point about his work is that it is grounded in careful and close looking at the real world, as his quote above makes clear. We can describe much of his work as an act of distillation, of finding details and observable qualities in settings, objects, and visual situations, and translating them into the purer context of art. Thus removed from their context, they become abstractions, while their link to the observable world remains a crucial aspect of their creation. Kelly’s creation of Austin was indeed his last great act of distillation, in which he took historical forms and influences and transformed them into his own purifying vision.

__________________________________________________________________

[1] John Coplans, Ellsworth Kelly (New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc., 1971), 28-29.

[2] Yve-Alain Bois, ed., “Ellsworth Kelly in France: Anti-Composition in its many Guises,” in Ellsworth Kelly: The Years in France, 1948-1954, (Washington D.C: National Gallery of Art, 1992), 9-36. Yve-Alain Bois, ed., Ellsworth Kelly Catalogue Raisonné of Paintings, Reliefs, and Sculpture, vol. 1, 1940-1953 (Paris: Cahiers d’Art, 2015), 9-12 and passim.

IMAGE CREDIT: Ellsworth Kelly, “Hôtel Saint-Georges, Paris (Self-portrait),” 1948, ink on paper, 12 1/4 x 17 5/8 inches (31.1 x 44.8 cm). ©Ellsworth Kelly Foundation. Photo courtesy Ellsworth Kelly Studio.