Oscar Muñoz: Chronology

Decade: 1970s

Chapters

Early 1970s

History

The geopolitics of the Cold War in Latin America contribute to the extreme polarization and violent action between insurgent groups and the Colombian government, as they battle for control of the country. Urban expansion continues in Cali; its growth rate is one of the most rapid in South America. Landmark historic buildings are replaced by modern architecture.

Art/Culture

Photography becomes integral to the international practice of Pop Art, Conceptual Art, and the development of realist and hyperrealist styles. Beatriz González, Alvaro Barrios, Antonio Caro, and Bernardo Salcedo adopt the strategies of Pop Art and Conceptual Art to explore the everyday, media culture, and political issues. They are linked to the international art scene, but their subject matter remains local. In Colombia, partly due to the so-called “boom” in Latin American literature, realism becomes important in photography, filmmaking, and literature. In Cali, Fernell Franco, Maria de la Paz Jaramillo, and Saturnino Ramírez pursue realist styles.1

The Artist

Muñoz graduates from the Departmental School of Fine Arts and rents a studio in Cali.

1970

History

On April 19, the Conservative Party candidate Misael Pastrana Borrero wins the presidential election over the candidate of a new third party, the National Popular Alliance or ANAPO, led by populist and former military dictator General Rojas Pinilla. Serious electoral irregularities inaugurate a decade characterized by corruption. The armed urban guerrilla group Movement April 19 (M-19) is founded in Bogotá, mostly by university students disaffected by the fraud in the recent presidential elections. Multiple sectors of society join general strikes.

Art/Culture

Important graphic art biennials begin to take place in Puerto Rico, which will inspire similar events in Cali. In May, the II Coltejer Art Biennial in Medellín features the breakthrough conceptual installations Hectare of Hay by Bernardo Salcedo and Almost Still Life by Beatriz González. Santiago Cárdenas wins an award as best Colombian artist. In November, the Pan-American Exhibition of Graphic Arts takes place at the X Cali National Art Festival at the Museum of Modern Art La Tertulia. It includes works by Antonio Caro, Beatriz González, and Jorge Posada (Colombian Shield). Bernardo Salcedo exhibits works like General Information that critics identify as Conceptual Art.2

The Artist

Muñoz exhibits at the Cultural Art Week at the School of Fine Arts, Cali.

1971

History

Cali inaugurates a new international airport and finalizes construction of the new campus of the University of Valle. In February, the police and army repress student protesters in Cali and their takeover of the new campus by killing between fifteen to thirty students, detaining six thousand people, and imposing a citywide curfew. Martial law is declared in Colombia until December 1973. In July, Cali, known as the Colombian sports capital, hosts the VI Pan American Games. Participants stay on the new university campus. The infrastructure built to host these games remains Cali’s top sports facility.3

Art/Culture

The printmaking collective Taller 4 Rojo, often focusing on political subjects, becomes active in Bogotá. In July, the Museum of Modern Art La Tertulia presents the I Americas Biennial of Graphic Arts in conjunction with the Pan American Games. The biennial is organized in part by Pedro Alcántara. Dario Morales wins first prize and Antonio Caro submits Salt, a relief made of salt. The Cali Vanguard Art Festival features Norman Mejía and Pedro Alcántara, with works characterized by clear social criticism.

The art center Ciudad Solar is founded in La Merced, a neighborhood in Cali’s historic center that is home to several cultural organizations. The founders are Francisco “Pakiko” Ordóñez, Miguel González, and Hernando Guerrero, whose family owns the property. Until 1973, Ciudad Solar functions as an alternative, collective art space, the first in Colombia to encourage experimental practices that could not always be presented at the Museum of Modern Art La Tertulia. Ciudad Solar sets the stage for the formation of the Cali Group, which includes Ramiro Arbeláez, Hernando Guerrero, and Oscar Muñoz, as well as important filmmakers like Eduardo Carvajal, Carlos Mayolo, and Luis Ospina. Some participants cofound the Cali Cine Club, which writer Andrés Caicedo directs from 1972 to 1977.

Artists such as Fernell Franco, Ever Astudillo, and Oscar Muñoz are part of the “urban generation” who witnessed Cali’s transformation from provincial town to large city, and who focus their work on urban themes through drawing, photography, documentary film, and literature. “We were all very interested in the phenomenon of the expansion of the city,” said Muñoz. “The 60s and 70s are decades when Cali has an astonishing expansion. Previously unseen phenomena now emerge—also in Medellín and Bogotá—and thus that interest in making a record of these cities: to gaze at what’s inside the theaters, as Miguel Ángel Rojas did, or visualize the pool halls, as was done by Saturnino Ramírez and Fernell Franco. There were the prostitutes of Buenaventura that [Franco] showed, the underworld characters, the young thugs of Oscar Jaramillo. The urban landscape is heavily featured.”4 In October, the Ten Years of Colombian Art exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art La Tertulia features work by Feliza Bursztyn, Beatriz González, and Bernardo Salcedo.

The Artist

Muñoz remembers Cali during this period as, “a very dynamic cultural environment, which inspired us. In my case, at the beginning, I got into drawing because here it was strongly promoted through the Biennial of Graphic Arts. Besides, it was what I did the most while I was in school: to draw with charcoal on pages of white paper.”5 Muñoz becomes interested in the work of Pedro Alcántara, Luis Caballero, Santiago Cárdenas, and Darío Morales.6 At the new art center Ciudad Solar, Muñoz meets many emerging figures in Cali’s art scene, such as Ramiro Arbeláez, Ever Astudillo, Andrés Caicedo, Eduardo Carvajal, Fernell Franco, María de la Paz Jaramillo, Francisco “Pakiko” Ordóñez, and Luis Ospina, along with well-established artists like Jan Bartelsman, María Thereza Negreiros, Edgar Negret, and Lucy Tejada. Muñoz forges a lasting friendship with Astudillo, Franco and Alcántara, learning from the latter various printing techniques. Muñoz joins the Graphic Experimental Workshop in Cali, a short- lived group dedicated to printmaking that is led by Alcántara and includes Astudillo, Jaramillo, and Phanor León. Although Muñoz produces some works with them, he does not remain an official member.7 In November, at the invitation of its director and curator, Miguel González, Muñoz mounts his first exhibition at Ciudad Solar. He includes his series Morbid Drawings, some of the last works he produced at school, showing distorted, elegantly dressed figures nude from the waist down. Muñoz’s work begins to receive critical attention. He is twenty years old.8 Besides film, video art also becomes a central interest during Muñoz’s formative years.

1972

Art/Culture

Miguel González is appointed curator of the Museum of Modern Art La Tertulia. In May, the III Coltejer Art Biennial is held in Medellín. In July and August, the Salon for Young Artists takes place at the Museum of Modern Art La Tertulia. Muñoz participates with his Morbid Drawings. In November, Muñoz is included in the XXVIII National Salon of Artists at the National Museum in Bogotá. At Ciudad Solar, Fernell Franco presents Prostitutes, his photographs of sex workers from Buenaventura.

The Artist

Muñoz draws distorted, elegantly dressed figures nude from the waist down. All his drawings have a vertical format. His new series Couples features similarly bisected images with erotic content.

1973

Art/Culture

The exhibition New Names in Colombian Art opens at the Museum of Modern Art of Bogotá in March. Muñoz participates with several works, including Lady, an erotic pastel drawing on craft paper. In October, the II Americas Biennial of Graphic Arts takes place at the Museum of Modern Art La Tertulia. Ciudad Solar moves to Cali’s El Peñón neighborhood. Under the direction of Francisco “Pakiko” Ordóñez and critic Alvaro Herrera, it remains open until 1977. Miguel Ángel Rojas begins his Faenza series, for which he secretly photographs encounters between gay men at B-movie theaters in Bogotá.

1974

History

In the first free elections since 1958 (when the National Front was instituted), Liberal Party candidate Alfonso López Michelsen is elected President of Colombia, governing until 1978. His administration supports modernization, including a divorce law and setting the age of majority at eighteen. Transport Central, Cali’s first centralized bus station, opens.

Art/Culture

Feliza Bursztyn exhibits her performative sculptures Beds at the Museum of Modern Art La Tertulia. In September, Muñoz wins first prize at the V Salon of Young Art at the Zea Museum in Medellín with his drawing Cries and Whispers.

The Artist

Muñoz creates linear drawings of female and androgynous figures with sensual content.

Mid-1970s

History

A boom in the illicit cultivation of marijuana (known as marimba in Colombia) on the Caribbean coast, a period called “Bonanza Marimbera,” begins. International dollars flood the local economy until the Colombian state, with support from the United States, intervenes to end this trade. The high price of coffee also contributes to economic prosperity, but rising inflation fuels the discontent of the working class.

Art/Culture

Cali street photographers take pictures of random people in the street hoping to sell them a portrait. They are known as fotocineros or “photo-cinema-tographers,” because they use discarded film stock for their photos, taken with an Olympus Pen camera.

The Artist

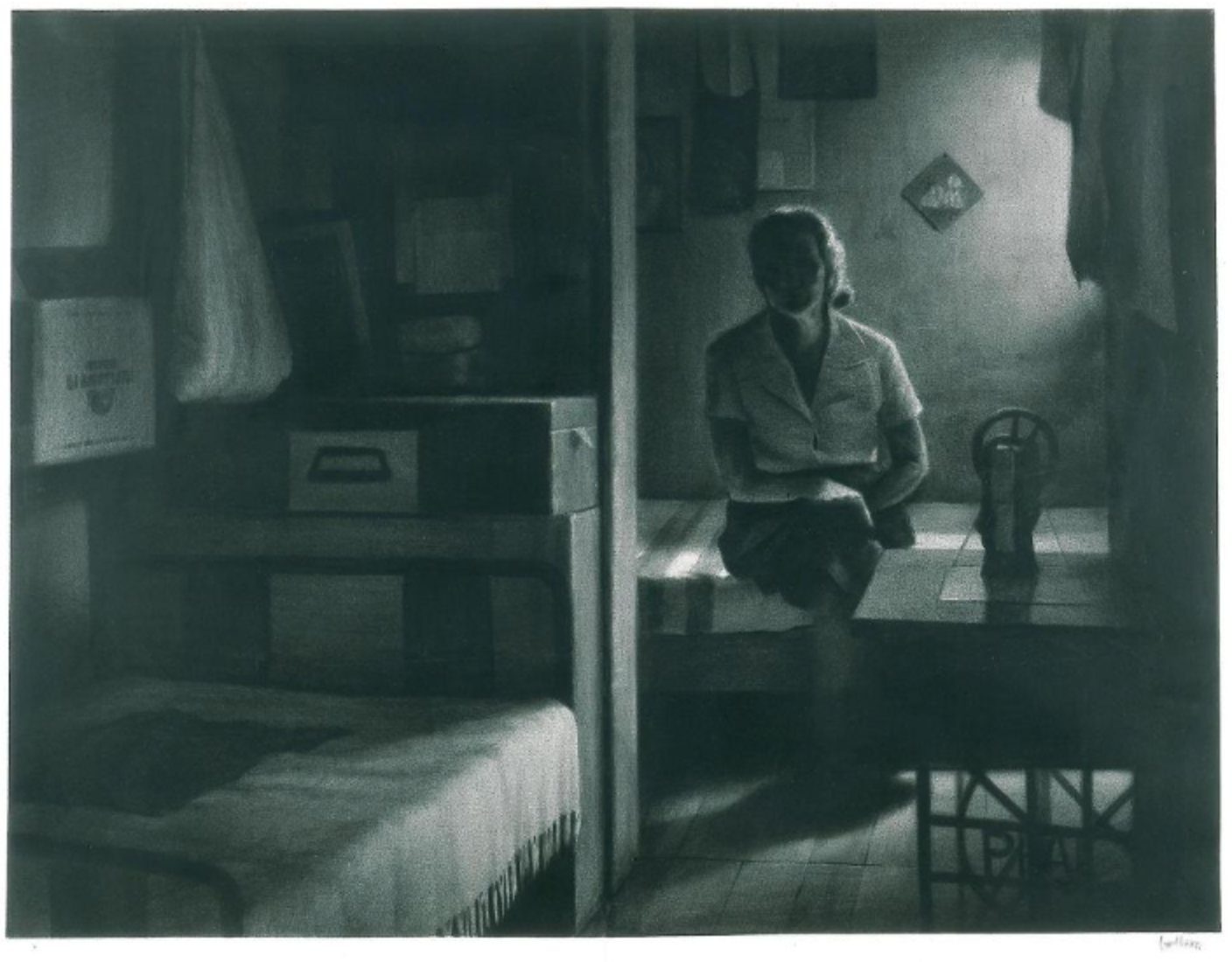

Muñoz slowly shifts toward photorealism, placing female figures in dark interior spaces and making their sensuality more subtle.

1976

Art/Culture

Between July and August, the III Americas Biennial of Graphic Arts takes place in Cali; Muñoz participates with his new series Tenements. Colombia’s National Salon, which has been losing support among leading artists, changes its organization to secure more regional participation. Under the new name XXVI National Salon of Visual Arts, it takes place in Bogotá, Barranquilla, Bucaramanga, Cali, Cartagena, Ibagué, Medellín, and Tunja. Its jury awards Antonio Caro’s Colombia–Coca- an honorable mention, indicating the acceptance of Conceptual Art in Colombia’s mainstream art institutions.9 Muñoz also receives a mention for his series Tenements.

Late 1970s

History

When the Colombian state bans marijuana, drug traffickers organize into cartels. The cartel in Medellín, controlled by Pablo Escobar, shifts from growing marijuana to importing coca and producing cocaine. Cartels launder their illegal earnings through the Colombian economy and invest in construction, sports, tourism, and other industries. As demand rises in the United States, the inflow of capital drives up inflation in Colombia.

Art/Culture

Workers, students, and intellectuals (including artists) become more openly critical of state policy, increasing social discontent. The Colombian government considers these groups as potential threats to democracy. Author Gabriel García Márquez and sculptor Feliza Bursztyn are exiled from Colombia. Cali-based drug traffickers assist the development of Salsa in their city through their connections to New York, where Salsa music is very popular in the Latino communities. Traffickers bring back records and engage local musicians to play this new dance music.

The Artist

Muñoz begins his drawing series entitled Interiors, depicting figures in dark domestic spaces who seem unaware of being observed. Sometimes the person represented is the artist’s mother, although her role is anonymous.10 He adopts a horizontal format to emphasize these spaces as urban landscapes. According to the artist he “wanted to capture the mood and atmosphere of those spaces through different wall textures, floors marked by the light, the shadows, the reflections on the mirror, and the accidents that architecture endures, the things that happen. That is what interested me the most, beyond a social discourse… In my works there is always a gaze that is not neutral, it is emotional.”11

Interested in exploring this hyperrealist aesthetic from a social and urban perspective, Muñoz begins a series of drawings titled Tenements, representing abandoned mansions in downtown Cali that were turned into overcrowded tenements. These dark works, loaded with charcoal, are based on photographs that he and Fernell Franco took in the city’s marginal neighborhoods.12 Although Muñoz is not interested in the photographic media per se, he becomes fascinated by the development process. “I have an indelible memory,” he recounts, “the first time I needed a photograph for my work and I was visiting Fernell Franco at his home, I entered his darkroom. And I saw how a pair of tongs began to move a white piece of paper in the developer bin to make an image appear. I was left bewildered, out of breath.”13 Muñoz purchases an archive from a photographic studio called Instantáneas Panamericanas (Pan-American Instant Photos) that was going out of business.14 Years later, he used this material as the basis of his project Bycontact Archive.

1977

History

Growing discontent with inflation, unjust social conditions, and urban unemployment leads to a massive national strike on September 14 that turns violent.

The Artist

Muñoz begins to show his work internationally. Drawings from his series Tenements are included in the exhibitions The Newest Colombians, organized by Marta Traba at the Museum of Contemporary Art of Caracas, and One Century of Colombian Art at the Casa de las Américas in Havana.15 His exhibition Tenements is presented at the Belarca Gallery in Bogotá, Barrios Gallery in Barranquilla, and the Center for Contemporary Art in Pereira.

1978

History

Liberal Party candidate Julio César Turbay wins the presidential election. His administration, ending in 1982, enacts measures that are ineffectual in curbing the increasing violence by the growing groups of insurgent guerrillas. Discussions about drug cartels enter the public discourse, but in the absence of state action, traffickers operate with impunity.

The Artist

Muñoz exhibits Interiors and Tenements in Paris at the 10ème Biennale, FIAC 78 (International Fair of Contemporary Art), presented by the Galerie Albert Loeb. He also participates in the show Lines of Vision, at the Center for Inter-American Relations, New York.16

1979

History

In January, the guerilla group M-19 steals weapons from a military base north of Bogotá. After the violence committed by drug cartels in Miami and New York, the United States and Colombia sign an extradition treaty, but Colombia backs out of it in the mid-1980s. Colombia is perceived in the United States as an exporter of marijuana.

Art/Culture

In the exhibition Ever Astudillo, drawings / Fernell Franco, photographs / Oscar Muñoz, drawings at the Museum of Modern Art La Tertulia, all three artists focus on the urban environment and popular culture in Cali.17 The Casa Pro-Artes opens in Cali.

Footnotes

1 Gina McDaniel Tarver, “Intrepid Iconoclasts and Ambitious Institutions: Early Colombian Conceptual Art and Its Antecedents, 1961–1975,” doctoral dissertation, The University of Texas at Austin, 2008, 12–20. Also, María Wills, “Entrevista retrospectiva a Oscar Muñoz,” banrepcultural.org <https://www.banrepcultural.org/oscar-munoz/entrevista-memorias-infancia-juventud.html>, accessed January 28, 2020. Santiago Rueda Farjardo, “Retratos de ciudad, billares, bicicletas, galladas y prostitutas: Fernell Franco, en corto diálogo con la fotografía colombiana,” Estudios Artísticos: Revista de investigación creadora, vol. 3, no. 3: 15–38. Digital Object Identifier (DOI): <https://doi.org/10.1448/ear.v3i3.12526>.

2 Tarver, “Intrepid Iconoclasts,” 213–14.

3 Yefferson Ospina, “¿Qué pasó en 1971 en Cali que cambió la historia de la ciudad para siempre?” ElPais.com, July 16, 2017, accessed March 4, 2020.

4 Muñoz, cited in Diego Garzón, Otras voces, otro arte: diez conversaciones con artistas colombianos (Bogotá: Planeta, 2005), 51.

5 Muñoz, cited in Garzón, Otras voces, otro arte, 50.

6 Garzón, Otras voces, otro arte, 51.

7 Katia González Martínez, Cali, ciudad abierta: Are y cinefilia en los años setenta (Bogotá: Ediciones Uniandes, 2012), 55–57, 157–63; Maria Iovino, Oscar Muñoz: volverse aire (Bogotá: Eco, 2003), 28, 76; Wills, “Entrevista retrospectiva.”

8 Wills, “Entrevista retrospectiva”; González Martínez, Cali, ciudad abierta, 197–99.

9 Tarver, “Intrepid Iconoclasts,” 39.

10 Miguel González, Oscar Muñoz (Cali: Cámara de Comercio de Cali, Departamento de Extensión Cultural, Festival de Arte de Cali, 1987); Wills, “Entrevista retrospectiva.”

11 Muñoz, cited in Wills, “Entrevista retrospectiva.”

12 Iovino, Oscar Muñoz, 32.

13 Muñoz, cited in Wills, “Entrevista retrospectiva.”

14 Erika Martínez Cuervo, “La obsesión por un bulto de imágenes,” Errata # 1, issue dedicated to Arte y Archivos, November 2010: 147–50; available at Issuu.com, accessed January 30, 2020.

15 González, Oscar Muñoz (1987); Iovino, Oscar Muñoz, 202.

16 González, Oscar Muñoz (1987).

17 González, Oscar Muñoz (1987).