MAJOR EXHIBITION

Border Vision: Luis Jiménez’s Southwest

OPENS

October 31, 2021

CLOSES

January 16, 2022

SHARE

About the Exhibition

Luis Jiménez lived most of his life in the American Southwest. Born in 1940 and raised in El Paso, Texas, he later settled in New Mexico, where he died in 2006. This area of the U.S., so near the border with Mexico, helped shape Jiménez’s artistic vision and his unique rasquache – or “underdog”– flair. Border Vision: Luis Jiménez’s Southwest explores his insightful and critical perspective on this region by focusing on key themes in his art: the history of western expansion and its lasting impact on Indigenous populations along the borderlands; the beauty and diversity of the local wildlife; and the vibrant contributions that immigrants and well-established Mexican Americans have made to the Southwest. Anchored by a selection of the Blanton’s extraordinary holdings of Jiménez works, this show seeks to celebrate the prominent Mexican American artist and recognize the enduring relevance of his artistic legacy.

All images on this web page are subject to copyright © Luis A. Jimenez, Jr. Copyright Trust / Artists Rights Society (ARS) NY.

Curated by Florencia Bazzano, Assistant Curator, Latin American Art, Blanton Museum of Art

Credits

Border Vision: Luis Jiménez’s Southwest is organized by the Blanton Museum of Art.

Support for this exhibition at the Blanton is provided in part by Ellen and David Berman.

Upcoming/Past Virtual Events

No Events

Image Gallery

Border Vision’s first section, Western Expansion presents artworks that focus on the history of western expansion and its lasting impact on Indigenous populations along the borderlands.

In Progress II, Luis Jiménez looks back at the nineteenth century, when millions of Texas longhorn cattle were trailed to markets in various parts of the country, turning the cowboy into a folk figure in the popular imagination. Jiménez said that he “was struck with the irony that our concept of the American cowboy was this John Wayne type image, this blond cowboy coming out of Hollywood, where in fact the original cowboys were Mexican. It was a Mexican invention. All of the terminology connected with the American cowboy is drawn from Spanish: corral, lariat, remuda.” This dynamic scene represents a lassoing, from the Spanish word lazo, the action of a horseback rider roping cattle with a lariat (la reata, in Spanish) in order to control it. The action hinges both literally and symbolically on a small patch of land, a fertile ground teeming with local fauna and flora, and equally rich in history lessons. The remains of a Native American warrior, whose feather-decorated, stone-tipped lance is clearly visible, symbolize the Indigenous bison hunters that succumbed to colonization.

Border Vision’s second gallery, Southwestern Traditions, addresses life in Texas and New Mexico, ranging from the beauty and diversity of the local wildlife, to the vibrant contributions made by Mexican Americans.

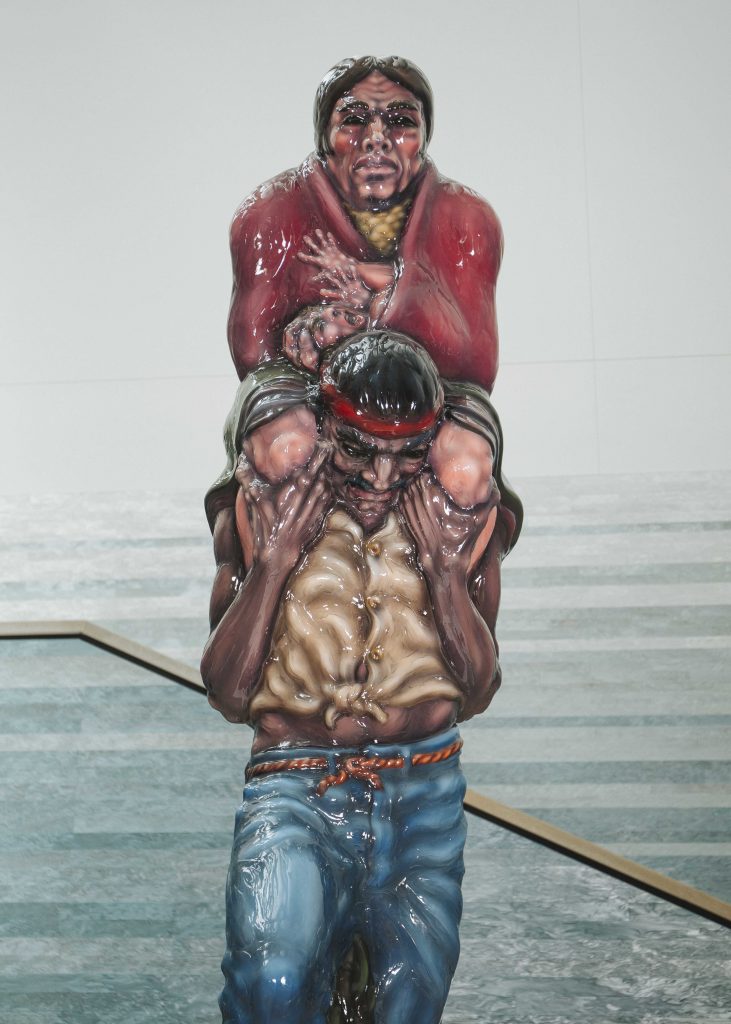

This monumental sculpture shows how immigration continues to be a complex and politically charged issue in the United States. When Luis Jiménez addressed this concern, he did so from the perspective of those forced by circumstances to look for a better life in the North. He affirmed, “I had wanted to make a piece that was dealing with the issue of the illegal alien… People talked about aliens as if they landed from outer space, as if they weren’t really people. I wanted to put a face on them: I wanted to humanize them.” In this sympathetic portrayal, he chose the theme of a family, and moved by the birth of his second child, he represented the woman holding a baby in her arms. “I went back to my experience in El Paso where this is a common sight,” the artist said. “The men carry the women across the river so they don’t get wet. In this case, she’s carrying a child. It was a way of consolidating the family idea and the idea of the illegal alien. It was dedicated to my dad.”

Luis Jiménez’s commitment to the Southwest also includes an appreciation of the local wildlife and of other animals, which he developed since he was a child. Alligators are not original to El Paso, but several live specimens were kept in a fountain decorating the city’s center for many years. Eventually, they were transferred to the local zoo as a protective measure. Jiménez remembers that “as a kid when I would go shopping with my grandmother or with my mother, we would take a bus and go to the downtown plaza… and then catch a streetcar to go to Juarez. It was important that the alligators were there because I was fascinated by them.” After receiving a commission from the city of El Paso for a public sculpture, he said, “I proposed bringing the alligators back, at least in fiberglass, because a lot of people remember them, and in Spanish we always called it La Plaza de los Lagartos, The Alligator Plaza.”

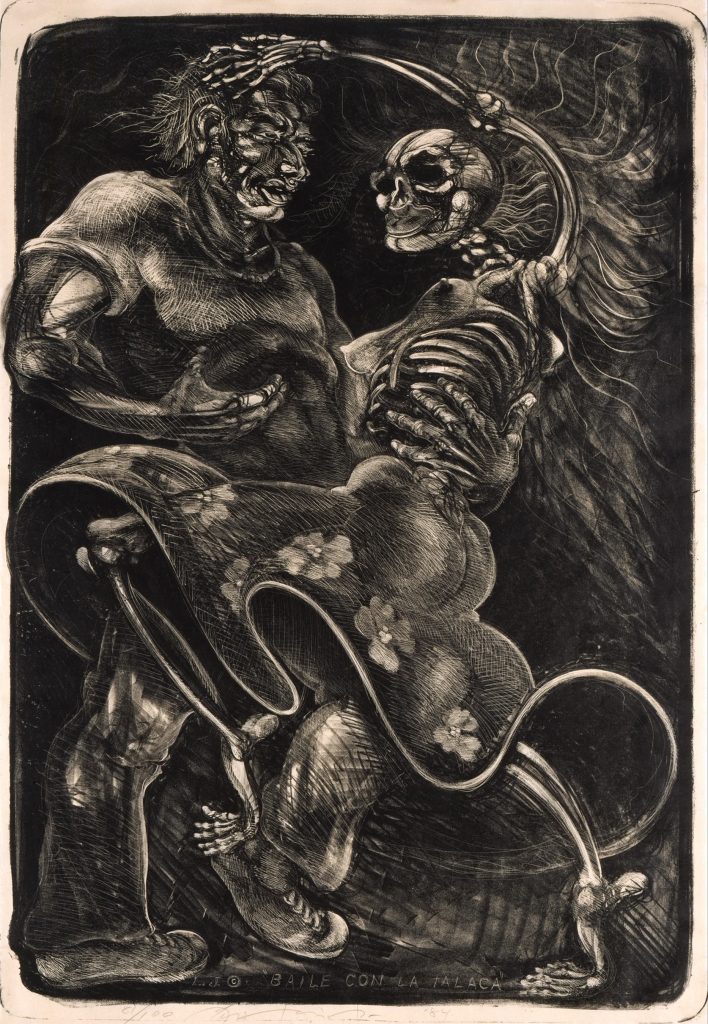

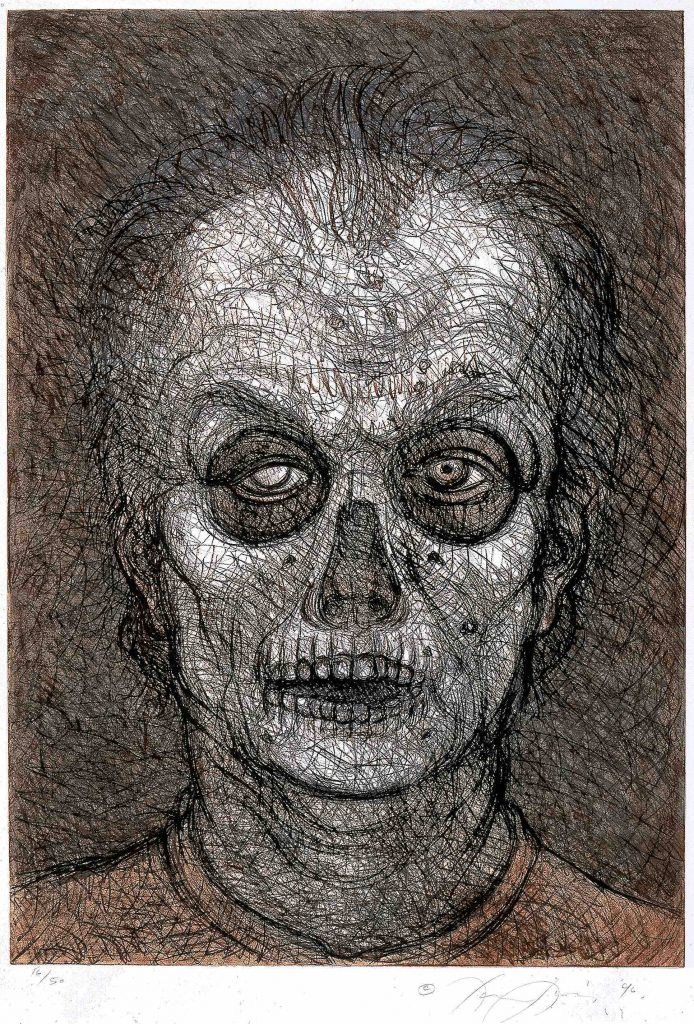

Luis Jiménez turns this representation of human mortality, an ancient art historical theme, into a deeply personal and cultural statement. Inspired by the Mexican tradition of the Day of the Dead which features skeletal figures, he represents himself dancing with Death, “la Talaca,” as this allegorical figure is called in Mexico (also known as “Calaca“). “Self-Portrait” also suspends the artist in that liminal space between life and death, but achieves this by superimposing three simultaneous images. At first, he seems to wear a mask or makeup for the Day of the Dead. But then, we also recognized it as a vulnerable portrait of the artist, showing the eye he damaged as a child and eventually lost. As the shape of his skull gains definition, the image becomes a radiographic vision of his internal bone structure, recognizing “death” as an integral part of our humanity.

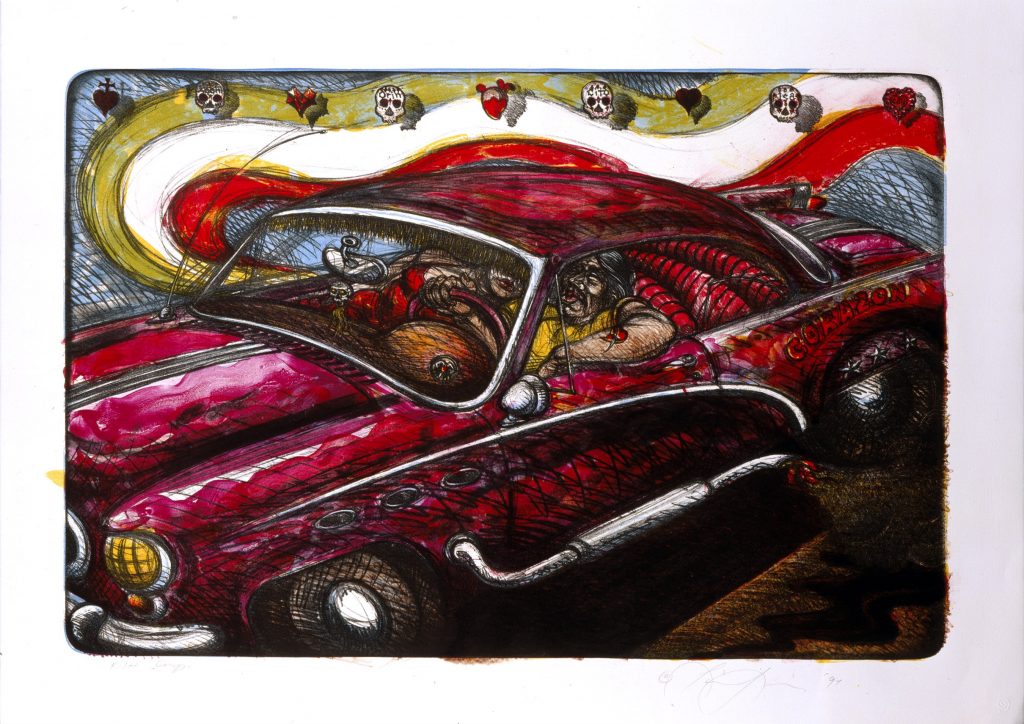

Luis Jiménez began to work as a child in his father’s electric and neon sign shop, learning early on how to handle industrial materials. As a teenager growing up in a strict religious household, he spent the money he earned on buying and restoring classic automobiles. Although the neon shop did not utilize fiberglass, Jiménez taught himself to use this material in order to finish and detail the exterior of these cars. In time, fiberglass would become a key element in his artistic practice, as he “decided that if my images were going to be taken from popular culture, I wanted a material that didn’t carry the cultural baggage of marble or bronze.” In addition, he has often featured vehicles in his artwork. This print depicts a lowrider, richly decorated with candy red paint and fancy upholstery. This type of customized car has been common in El Paso and throughout the Southwest, generating visual styles that have often inspired Chicanx artists.

Press

Feature Image Credit

Luis Jiménez, Border Crossing [Cruzando el Río Bravo], 1989, painted fiberglass, 126 x 40 x 51 in., Blanton Museum of Art, The University of Texas at Austin, Gift of Jeanne and Michael Klein, 2013