Seeing the Obvious: Vito Acconci’s “Wav(er)ing Flag”

March 3, 2021 by Genevra Higginson

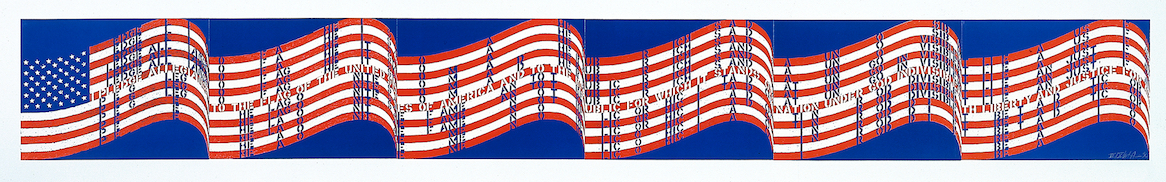

Sometimes art can appear, at first glance, rather obvious. Such is the case with Vito Acconci’s Wav(er)ing Flag (1990), a twelve-foot long series of six lithographic prints. Together, the sheets depict the flag of the United States of America, elongated and billowing, with the Pledge of Allegiance inserted as if the flag’s stripes were the ruled lines of notebook paper. Such a work raises certain questions: What draws an artist to create pictures based on already ubiquitous imagery? Does the immediate legibility of something like a national flag make an artwork less powerful or less imaginative than, say, abstract or impressionist art?

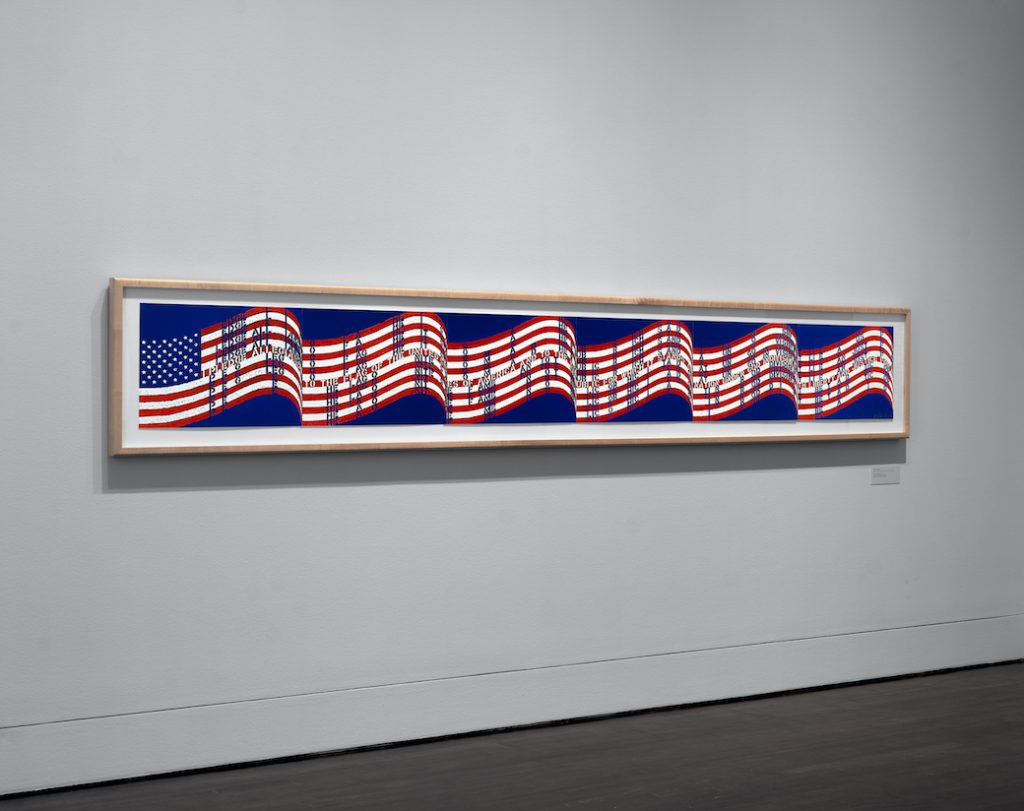

Wav(er)ing Flag takes up an entire wall, hanging almost like a paper sculpture. The print is based on Acconci’s proposal for a project at the St. Louis Convention Center comprised of stainless steel panels etched with the Pledge and illuminated by red, white, and blue neon lights. Though the project was never realized, the monumental lithograph it inspired activates the spaces in which it is displayed.

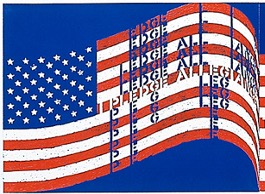

The scale of this artwork demands attention. So too does its dissection of familiar forms, which invites closer scrutiny. Viewers move left to right, and back and forth, to notice all the print’s details. As we move along from one sheet to the next, we follow Acconci’s repetitions: of the rippling flag, of extracted words, and even of extracted letters. Playing with the text, Acconci variously highlights and obscures different parts of the Pledge. Thus, the word “Pledge” becomes “ledge”, then “edge”, and then, below, “peg”. “Allegiance” becomes “all”. “The” becomes “he”. “Flag” becomes “fag” and “lag”. Even the spaces between words create new expressions, so that “of America” becomes “fame”.

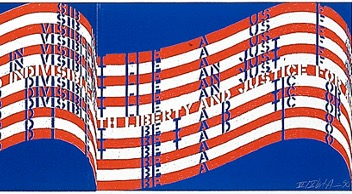

As we approach the edge of the last page in the print series, we encounter more unraveled words. “Liberty” breaks out into “lie”; “justice” into “just.” The final word in the pledge, “all”, is hidden in the undulating form of the flag.

The sum of this artwork’s parts reflects Acconci’s artistic practice. Born in the Bronx, New York, Acconci studied literature before earning an MFA at the University of Iowa’s Writers’ Workshop in 1964. Today, Acconci is best remembered for his body and performance art, largely from the 1970s. Yet an interest in language and systems permeate all of Acconci’s artistic output, from poetry to performance to installation.

By the 1980s, Acconci came to the conclusion that artworks are incomplete without the participation of the viewer. Interested in activating public spaces, Acconci therefore turned towards architecture. He expressed his ethos in this series of questions: “Can you make that main space less sure of itself? Can you cast a doubt, show hesitation, insert a parenthesis, a second thought?”

Standing in front of this monumental pairing of word and image, we activate the artwork. It is as if the print transforms our surroundings into a locational comma. By directing us to pause, the print forces us to confront the words and symbols that ostensibly represent a nation founded on ideals of equality. But as we discover the hidden words that Acconci extracted, we start to question such fundamental “truths”. Does “just” mean fair, or does “just” mean only? Are these promises for all, or are they reserved for certain members of society—namely, cis-gender men that conform to whiteness, heterosexuality, and other exclusionary norms?

Still, demonstrating that “justice” contains the word “just” is not, in itself, revelatory. In fact, it is quite obvious. So, to return to the original question, does that obviousness negate the artwork’s impact? Other works play similarly with familiar forms. Frank Stella’s meticulous and highly regulated linework, and Andy Warhol’s riffs on soup cans, and Jasper Johns’ series on numerals can all fall into this category. Indeed, Johns’ most iconic works are his repeated reinterpretations of the American flag.

The recasting of easily identifiable forms helps us question what constitutes identity. It is critical to interrogate our shared spaces, our blind spots, and ourselves. Through that process of reflection, the inequity and injustice built into societal structures become as apparent as the structures themselves. And recognizing that obviousness is crucial. Thus, the confrontational obviousness of Acconci’s Wav(er)ing Flag challenges us to see, critique, and unravel the realities of systems that divide rather than build.

This artwork is on view as part of the Paper Vault exhibition Off the Walls: Gifts from the Professor John A. Robertson, November 8, 2020 – March 14, 2021, Blanton Museum of Art, The University of Texas at Austin.

This blog post was written by Genevra Higginson, Curatorial Assistant, Prints and Drawings, Blanton Museum of Art.