Women’s History Month 2022: #5WomenArtists from the Blanton’s Collection

March 2022, by Rachel Urbano

In honor of Women’s History Month and to participate in the ongoing #5WomenArtists campaign led by the National Museum of Women in the Arts (NMWA), we’re highlighting five artworks made by women in five different centuries. These artists demonstrate diverse creative practices, ranging from traditional printmaking techniques, to ritualistic performance and photography, to contemporary portraiture. Drawn from the Blanton Museum’s works on paper collection, each artwork serves as one strand in a vast, woven landscape of women’s histories. Each woman’s story and practice are idiosyncratic to her time, place, and circumstances, contributing to a history of female identity that defies a monolithic understanding of womanhood and what it means to be a woman artist.

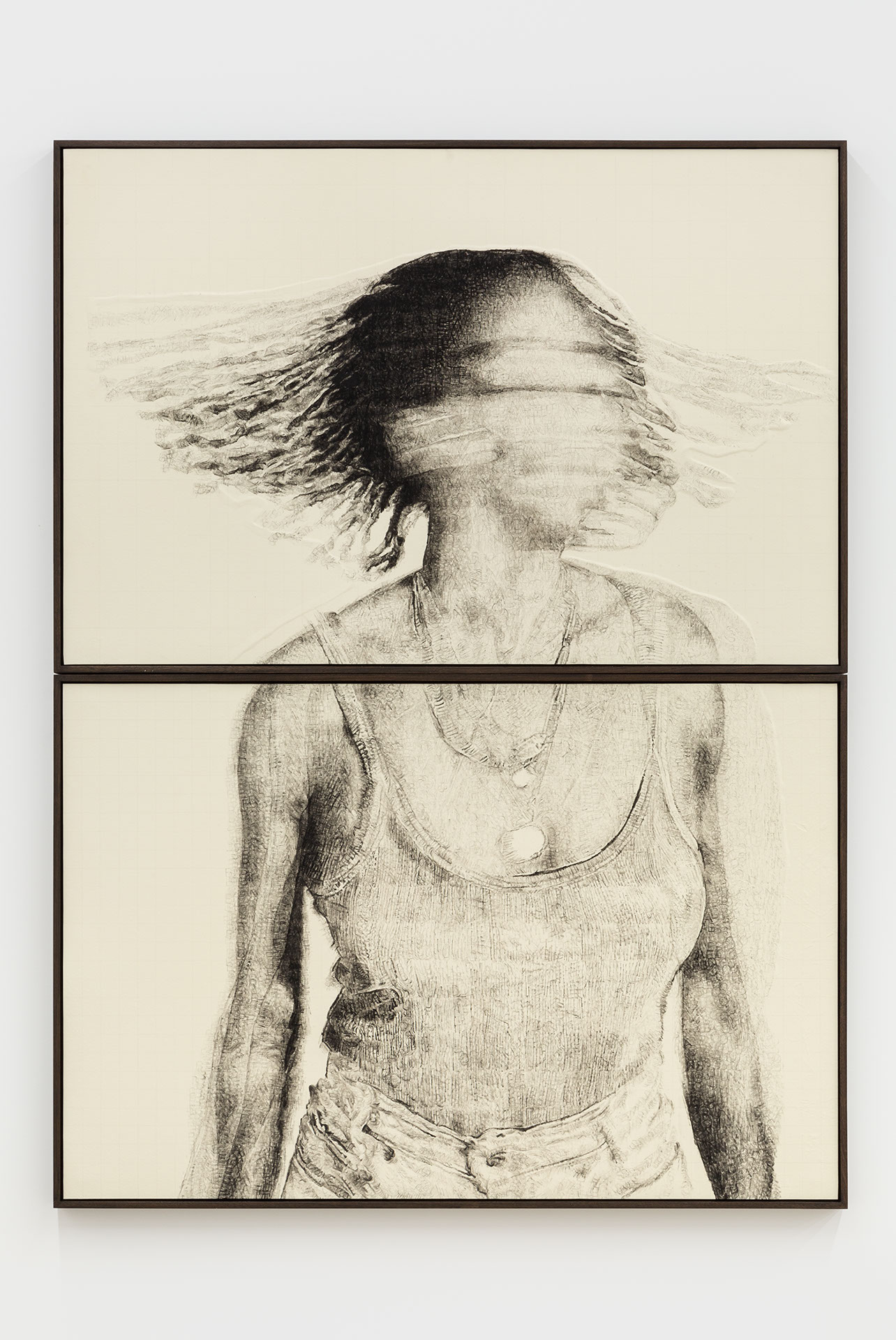

Kenturah Davis (Altadena, California, 1980–present)

Kenturah Davis’s Breath as a Boundary (2018) is not a typical portrait. The subject, a young Black woman, appears as a blurred profile, caught in motion with swirling braids. This visual effect of blurring and obfuscation is an important thread throughout Davis’s work. While it is not readily apparent, Davis uses the letters from the work’s title Breath as a Boundary to create the portrait with letter stamps. The woman literally embodies the text in the form of ink on paper, but these letters are virtually indiscernible in the completed work. According to Davis, “The pairing of poetic phrases with blurry images offers a path to think about the grey areas in language and even in our lexicon’s failure to adequately describe some kinds of experiences.” Davis embraces the slipperiness of language by depicting her subjects in a state of flux––the woman in this portrait is dependent upon the phrase that forms her body, while simultaneously obscuring it. Davis states, “We often use language to carve out distinctions between one thing and another. I want to complicate ideas about meaning, reception, and perception . . . and have found refuge in blurring and doubling to do this.”

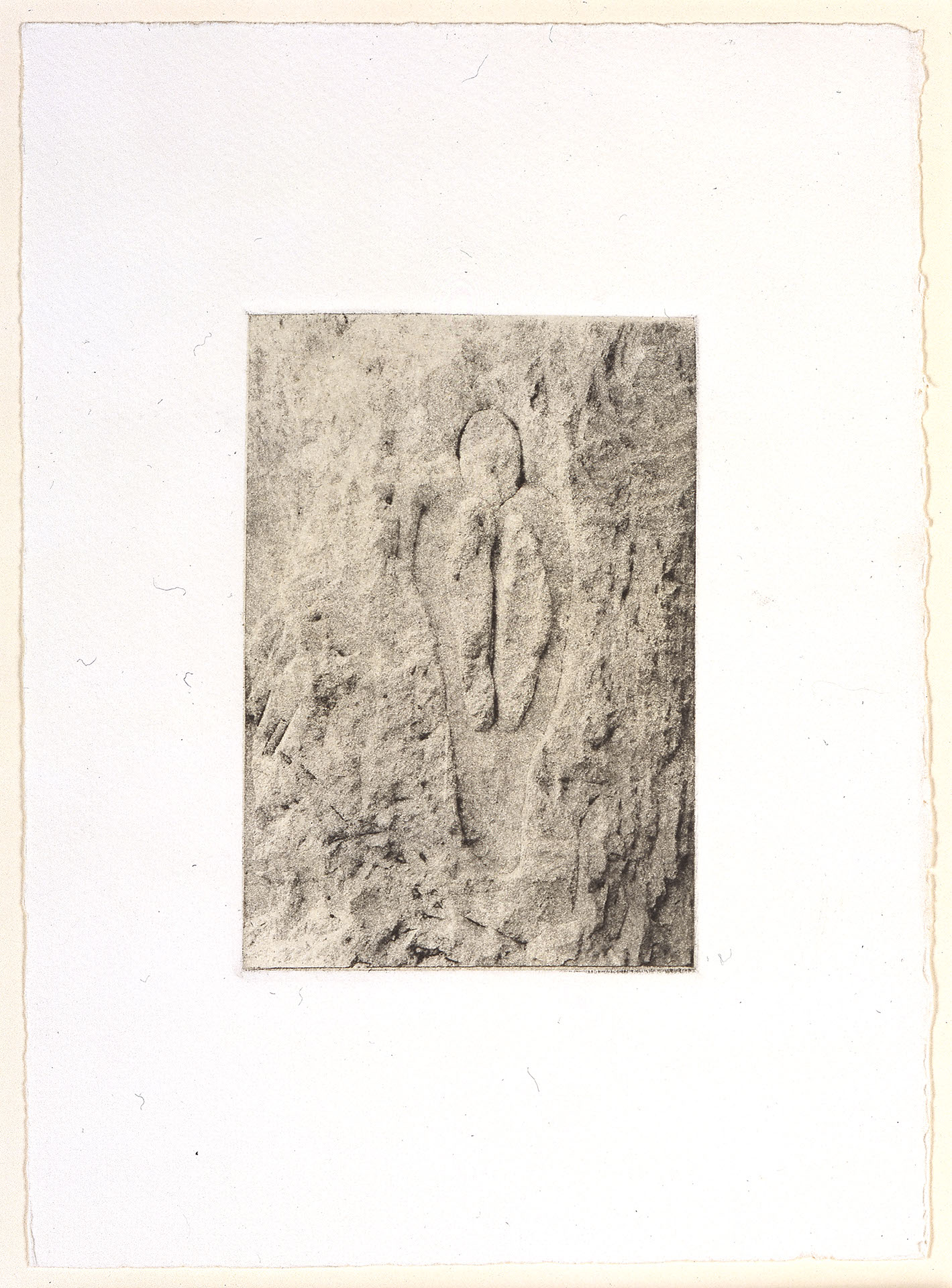

Ana Mendieta (Havana, Cuba, 1948 – New York City, 1985)

Cuban-born Ana Mendieta used her own body in performative actions that evoked feminist connections to the environment and Afro-Caribbean spiritual practice. When she was twelve years old, Mendieta’s counter-revolutionary parents sent her unaccompanied to live in the United States. Two decades later, Mendieta returned to Cuba for the first time since her exile. She began creating her Esculturas Rupestres series (Rupestrian Sculptures) in Jaruco National Park outside of Havana, which is known for its extensive limestone hills and as an important site for the indigenous Taíno people. The Rupestres works (the term “rupestrian” referring to art done on rock or cave walls) are an extension of Mendieta’s powerful Silueta series (1973-78) where she made impressions or silhouettes of her body directly into the land or by using natural materials to mark the outline of her figure.

This work’s title Atabey refers to a supreme deity worshipped by the Taíno, who was revered as the goddess of fresh water sources and fertility. Mendieta carved these sculptures into the natural limestone in low-relief, and while she meant for them to be discovered by future visitors to the park, they were ultimately destroyed by erosion. The ephemeral carvings resemble Pre-Columbian petroglyphs, thereby pointing to Cuba’s indigenous past. They are able to live a second life through the photographs Mendieta took on-site, now existing as prints that preserve a part of her ritualistic interventions on the natural land.

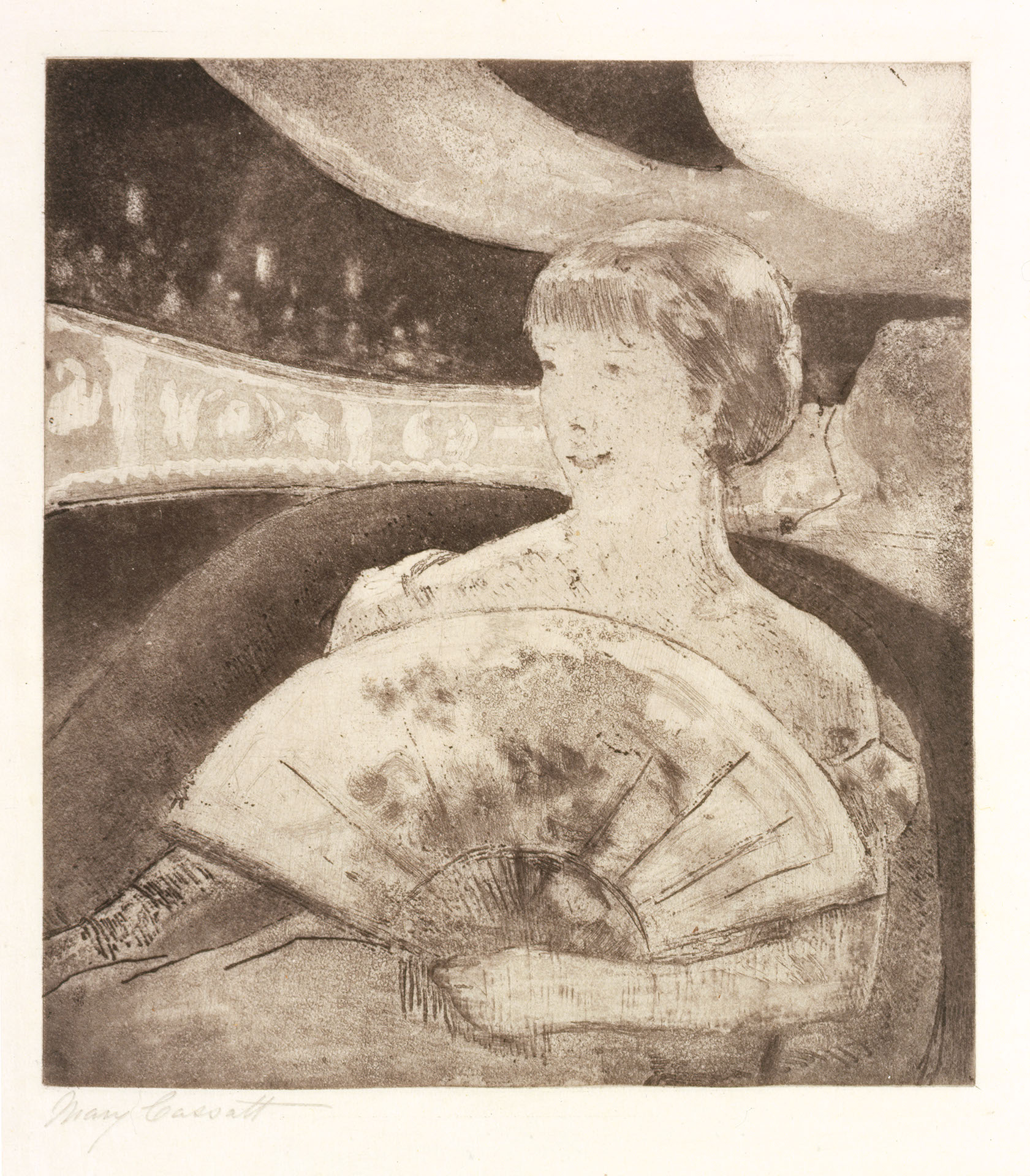

Mary Cassatt (Allegheny City, Pennsylvania, 1844 – Le Mésnil-Theribus, France, 1926)

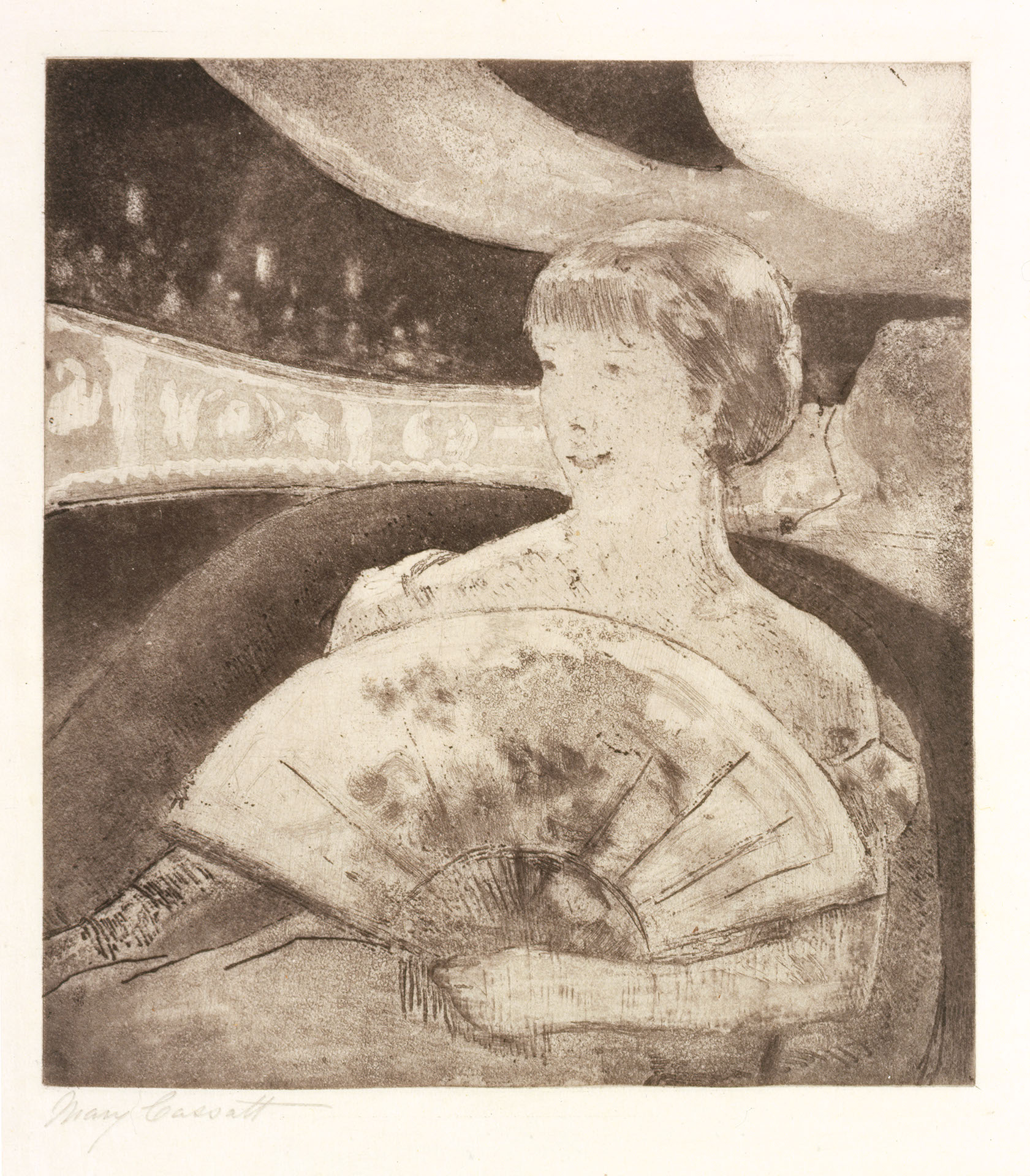

One of the most famous artists among the French Impressionists is American-born Mary Cassatt. She first arrived in Europe to study art in 1865. Despite Paris’s male-dominated art scene, Cassatt had a painting chosen for the Paris Salon in 1868, where Edgar Degas encountered her work. Degas became a mentor to Cassatt and encouraged her to explore the graphic arts in addition to painting. In 1877, Degas invited Cassatt to join a cohort of artists that would later become known as the Impressionists. Along with Eva Gonzalès, Marie Bracquemond, and Berthe Morisot, Cassatt held her own as one of the four women artists that were a part of the Impressionist circle. After joining the group, Cassatt transformed her artistic style and approach to color and light, developing a language of her own to depict her subject matter of choice: middle-class women enjoying such leisure activities as the opera and theater, as well as domestic scenes of women and their children.

In addition to her well-known works in paint and pastel, Cassatt made over 220 prints. In the Opera Box (No. 3), Cassatt uses the intaglio printmaking techniques of aquatint and soft-ground etching to create varied tones and forms with soft edges. Cassatt organizes her composition into foreground, middle-ground, and background as separate areas of tone that capture a range of highlights and shadows: the bright tone of the woman marks the foreground; the darkened area directly behind the woman defines the middle-ground; and both highlights and shadows create a hazy background.

Anne Allen (London, England, 1749–1808(?))

Among the recent additions to the Blanton Museum’s collection is this print by Anne Allen. Little is known of Allen’s life. She began making etchings after Jean-Baptiste Pillement’s drawings in the 1770s; the two married in 1799. After Pillement’s death in 1808, Allen is documented as living in Paris, but the date of her death is unknown. Her existing body of work comprises forty-five etchings made after fantasy flower and chinoiserie drawings by Pillement. Allen produced these prints using two printing plates, each bearing part of the design. She applied colored ink directly to each plate using a ball-shaped wad of cloth known as a “poupée.” Printed one after the other on the same sheet of paper, the plates create a multicolored, complete design. Many artisans found these whimsical designs useful in constructing patterns on ceramics, textiles, and wallpaper. Come see this print in the Blanton’s current exhibition Fantastically French! Design and Architecture in 16th- to 18th-Century Prints, on view from March 5th – August 14th, 2022.

(Written by Christine J. Zepeda).

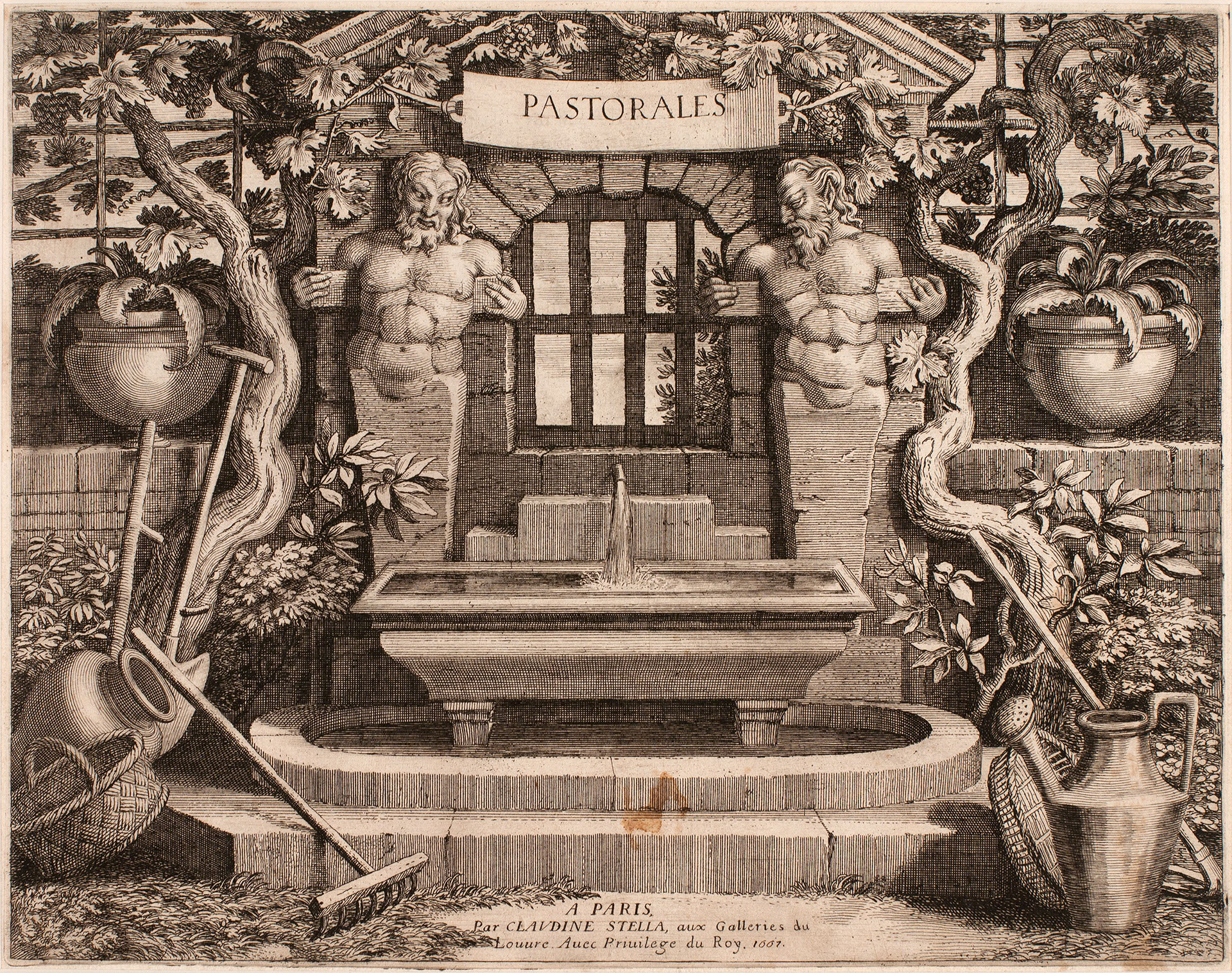

Claudine Bouzonnet Stella (Lyon, France, 1636 – Paris, France, 1697)

While still a teenager, Claudine Bouzonnet Stella joined her uncle Jacques Stella’s workshop in Paris where he served officially as Painter to the King. When her uncle died in 1657, twenty-one-year-old Claudine was named head of the workshop and given exclusive royal permission to continue producing prints after her uncle’s designs––a rare privilege for a young woman artist at that time. This etching is the frontispiece for a series of sixteen prints titled Pastorales, featuring an idealized country life of peasants and shepherds. Scholars previously assumed that the Pastorales were made after her uncle’s designs, but more recent scholarship reveals that Claudine was the sole designer of these prints since no matching drawings or paintings by Jacques have ever been recorded. This scene presents a delicate balance between human cultivation (indicated by the watering can and rake) and nature’s raw power: vigorously twisting vines and satyr herms that seem to strain against the architecture that encloses them. This print is also in Fantastically French! Design and Architecture in 16th- to 18th-Century Prints, on view from March 5th – August 14th, 2022.