Women’s History Month 2023: #5WomenArtists in Day Jobs

March 2023, by Meg Burns, Curatorial Administrative Assistant, Blanton Museum of Art

Since 2016, the National Museum of Women in the Arts (NMWA) has been asking a simple question: can you name five women artists? This question has sparked conversations on the underrepresentation of women in museum collections, galleries, and academic scholarships. You may have seen the hashtag #5WomenArtists circulating every March since 2016, encouraging the discovery of new and exciting creators.

Similar to how the NMWA seek to highlight women’s unsung artistic labor, the exhibition Day Jobs questions the connection between creative output and economic reality. The aim of the show is not to glorify an artist’s day job but to draw back the curtain from the rarefied world of fine art. Often, we imagine artists as isolated geniuses, but in reality, art and everyday life are in constant conversation. Many times, an artist’s day job can be a source of inspiration, a new material fascination, or just a stable income that enables extracurricular experimentation. Curator Veronica Roberts specifically focused on US-based artists working after World War II in order to include women working in a variety of professions outside the home. Of the 38 artists represented in the exhibition, 15 of them are women, ranging from up-and-coming sculptors to the godmothers of textile art and multimedia installation. Here are five women artists featured in Day Jobs that we think you should know.

Vivian Maier (New York, New York, 1926 – Oak Park, Illinois, 2009)

Vivian Maier was an American street photographer based primarily in Chicago and New York. While she captured over 150,000 photographs from the early 1950s through 1986, Maier never exhibited her artwork during her life. It wasn’t until 2007, when real estate agent and amateur historian John Maloof purchased a box of her photographic material at a Chicago auction house, that Maier’s work was brought to public attention.

In life, Vivian Maier worked as a nanny for over forty years in New York, Chicago, and Milwaukee. She is remembered by her charges as a fiercely private and often contradictory person, sometimes a playful caretaker, at other times, aloof and cruel. She carried her Rolleiflex camera with her always, and would take the children out on “shooting safaris” to capture images in different neighborhoods throughout the city. The resulting photos—wry, brilliant, shocking, or moving, but always keenly observed—have drawn comparisons to work by Weegee, Diane Arbus, and Robert Frank. As Rose Lichter-Marck argues in her New Yorker profile, Maier did not assume the persona of “mystical flâneur” taken up by so many street photographers, but perhaps she leveraged the invisibility of her role as hired help and her trained eye as a childminder to recognize and capture transformative everyday moments.

Howardena Pindell (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1943 – New York, New York, present)

After receiving her MFA in painting from Yale University in 1967, Howardena Pindell moved to New York and began working at the Museum of Modern Art, where she would remain for over a decade, rising to the status of associate curator. Working during the day and returning to a modest, shared apartment at night, Pindell found herself without the natural light necessary to create the bold, figurative oil paintings that she favored during graduate school. Instead, she turned to hole punched manila folders, glitter, squishes of paint, grid paper, and other unlikely materials glued or sewn to reassembled strips of canvas. As Naomi Beckwith describes in her essay “Body Optics, or Howardena Pindell’s Ways of Seeing,” “The objects she creates [in this period] are eminently tactile; the artist feels things out. Pindell, in a way, works blind.” Although born of necessity, this material shift represents a significant formal innovation for Pindell, who continues to utilize multimedia collage in her practice to this day.

After a car accident in 1979 left Pindell severely injured and with memory loss, the artist began engaging in personal content more directly, including her extensive Autobiography series. This series, including Autobiography: Japan (on view in Day Jobs), reconstitutes important memories in Pindell’s life—her travels, current events, key influences, family history—through complex, multimedia canvases. Despite pressures in the 1960s and ’70s to either embrace apolitical abstraction or paint solely for the cause of racial justice, Pindell refused this separation of form and context. Her work is unapologetically feminist and antiracist, layered in the realities of her experience in the world as a Black woman.

Violette Bule (Valencia, Venezuela, 1980 – Houston, Texas, present)

Violette Bule is a Venezuelan-Lebanese conceptual artist and photographer, now primarily based in Houston, Texas. Trained at the Escuela Activa de Fotografía in Mexico City and the Centro Nacional de la Fotografía in Caracas, Bule uses her photographs and installations to critically examine social issues like immigration, nationalism, and incarceration. Many of Bule’s most recent projects have arisen from the various jobs she has held to make ends meet, including Someone in my car (based on her time as a ride-share driver) and Someone in my bed (based on her experience hosting a room for rent).

Bule’s Homage to Johnny (2019), a sculpture featured in Day Jobs, pays tribute to a coworker of the artist’s from her time working at a bakery in New York. A recent immigrant from Mexico, Johnny worked long hours as a dishwasher but was paid less than other employees—in part because he could speak neither English or Spanish, only the Indigenous language Nahuatl. Bule’s sculpture is crafted from nearly 1500 forks, attached by magnets to hulking grates that once covered the sidewalk entrance to a New York restaurant basement. Perhaps the triptych shape indicates that Homage could be an altarpiece to Johnny and his tireless dedication. Alternatively, the mass of tenuously connected forks may indicate the precarity of Johnny’s situation and that of immigrant laborers as a whole.

Jay Lynn Gomez (San Bernardino, California, 1986 – Boston, Massachusetts, present)

Born and raised by immigrant parents in southern California, Jay Lynn Gomez uses her artistic practice to examine the intersections of labor, class, race, and the art world. After briefly attending CalArts, Gomez took a job as a nanny for the young twins of a Hollywood film editor. Living with and caring for this wealthy family brought important questions to the surface for Gomez: What labor is necessary to maintain the lifestyles of the rich? Which employees are allowed to be seen? Which employees are “indispensable” and which are never missed?

On breaks and during the children’s naptime, Gomez flipped through the pages of discarded luxury magazines with interiors that mirrored her own surroundings. She began to paint the missing workers—housekeepers, seamstresses, groundskeepers, janitors, nannies, often immigrants and people of color—into the scenes, asserting the unspoken reality of the labor that maintained the opulence. What began as a project posted onto her “Happy Hills” blog has grown into an expansive, multimedia practice that she hopes catches the eye of collectors and workers alike: “It’s the whole point of this project to give people pause, to get people to stop, if only for a moment, and think.”

Sara Bennett (Toronto, Canada, 1955 – Brooklyn, New York, present)

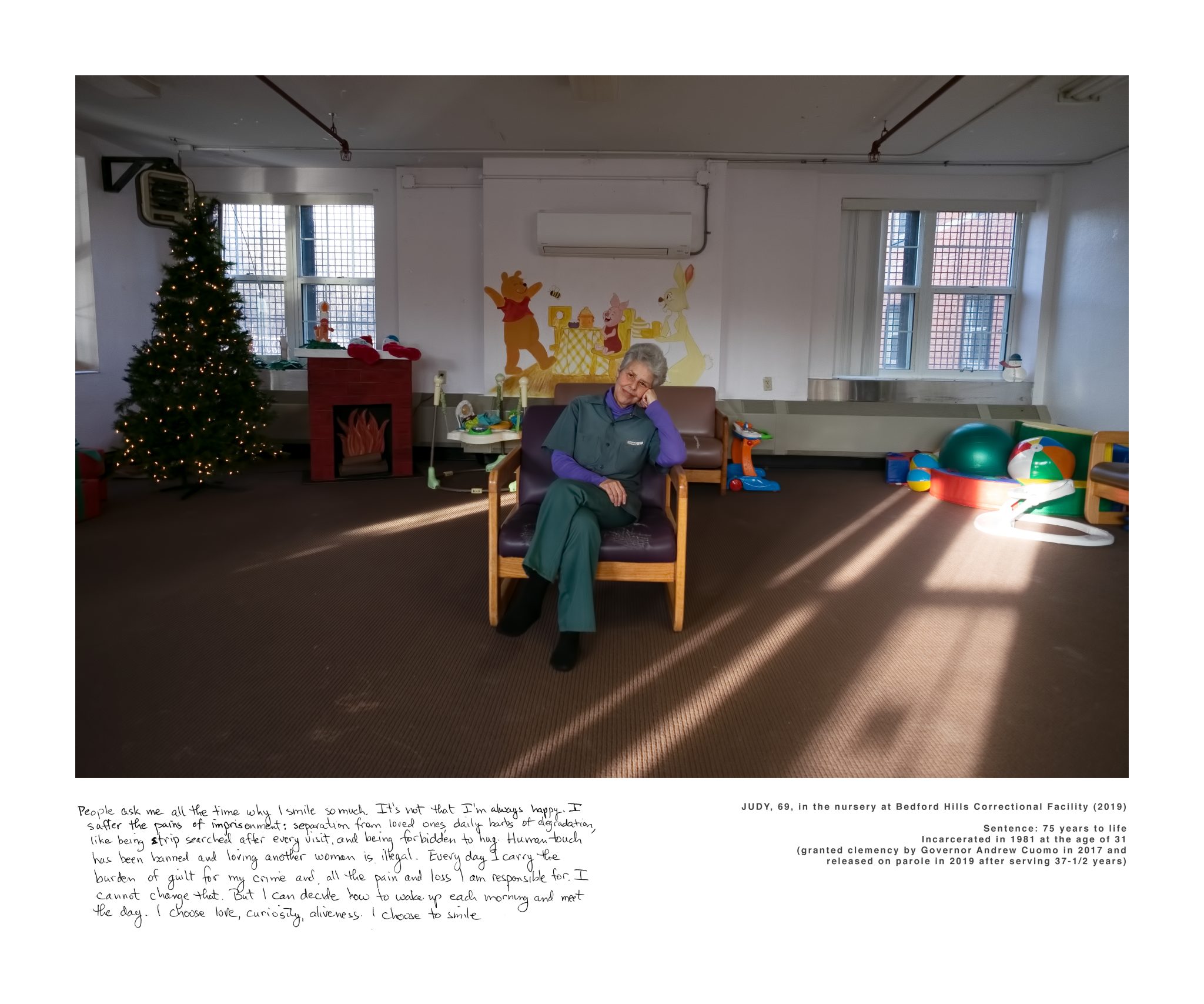

Brooklyn-based photographer Sara Bennett spent nearly two decades working as an appellate attorney for the public defender’s office. In 2009, after taking on the case of Judith Clark, a woman who had completed 26 years of a 75 years-to-life sentence, Bennett picked up her camera in hopes of convincing the public (and the governor of New York) to grant Clark clemency. Bennett’s photographs of Judy and the women to whom she was a mentor and friend, collected in Spirit on the Inside: Reflections on Doing Time With Judith Clark, generated an immense public response. “I realized that people actually don’t know hardly anything about who’s in prison,” Bennett said. “All they know is what you read in the newspaper, but they don’t think about the lives they’ve left behind or the lives they’ve created or the kind of people they have become.”

Bennett’s photographic advocacy work did not stop with Judy Clark. Instead, Bennett has spent the last decade photographing current and formerly incarcerated women; images that she hopes will illuminate the dignity and humanity of her sitters, and the pointlessness of long sentences and barriers to societal reentry. In Bennett’s words: “As a lawyer, I helped one person at a time, case by case. But as an artist, I have an opportunity to show the scale and enormity of the carceral state.”

Listen to an audio interview excerpt with Sara Bennett (includes transcription).

Wonderful article about such a meaningful exhibit. Bravo to the curators of Day Jobs!

To see that artists who have easily been overlooked are able to share their craft and vision is inspiring and makes me hopeful we will see more exhibits like this moving forward.

Meg,

I enjoyed reading your blog.. Keep up the Good Work-

This blog, exhibit, and concept was not only eye catching but awe inspiring, relevant, and best represents today’s pro artists as well as the freelance and entrepreneurial communities as a whole and at large. It especially resonated with me as both a visual artist and entrepreneur currently pursuing her BFA and BSBA in undergrad. As Erin Haffner mentioned earlier, I too am hopeful that we will see more exhibits like this one in the future. Thank you so much. This exhibit couldn’t have come at a better time!

-Cheri Regis

Parkville, MO