Las Hermanas Iglesias: The Deities in the Details

June 2023, by Itza Cantera-Guerrero, Spring 2023 Marketing & Communications Intern, Blanton Museum of Art

As someone who loves looking at tiny details and conducting research, I was immediately drawn to the nine collages in the Blanton’s Contemporary Project exhibition by Las Hermanas Iglesias, the artistic collaboration between sisters Lisa and Janelle Iglesias. From far away, the collages’ vibrant, contrasting colors call out to you. Up close, one starts to notice collaged photographs of figures and objects in gray tones that contrast with the bright colors of the backgrounds. Their imagery includes shells, figurines, and plaster casts of the sisters’ and their family members’ hands. The untitled collages are part of the artists’ ongoing seasaw / seesaw series, which combines found images with photographs of Las Hermanas Iglesias’ sculpture. Because little details can alter one’s perspective on an artwork, I wondered what the figurines in these collages represent and how they relate to the exhibition’s theme of caregiving. What I discovered was that these figures are those of fertility deities and warrior talismans from various cultures. I focused on three of them to better understand how they support the conversation Las Hermanas Iglesias have created in their exhibition.

Venus of Willendorf

A prominent figure in the seasaw / seesaw collages is the Venus of Willendorf. In 1908, archaeologists working in a small Austrian village called Willendorf uncovered one of the oldest surviving art objects, believed to have been made 25,000 to 30,000 years ago. Based on the features of the figure, scholars believed it depicted Venus, the Roman goddess of love, fertility, and beauty.

Given the sculpture’s potential cultural significance, the Venus of Willendorf’s size is fascinating. The figure is under 4.37 inches tall, meaning that one can fit the object in the palm of their hand and potentially take it wherever they desire. This portability would have been beneficial given the nomadic lifestyles of some ancient civilizations, and would have differentiated this object’s admiration from that of other Venus sculptures. The person who may have possessed this object had a personal connection to the figure. They could privately admire the deity anytime and anywhere they wanted. The energy of the figure would always transmit to them.

Taíno Goddess of the Moon

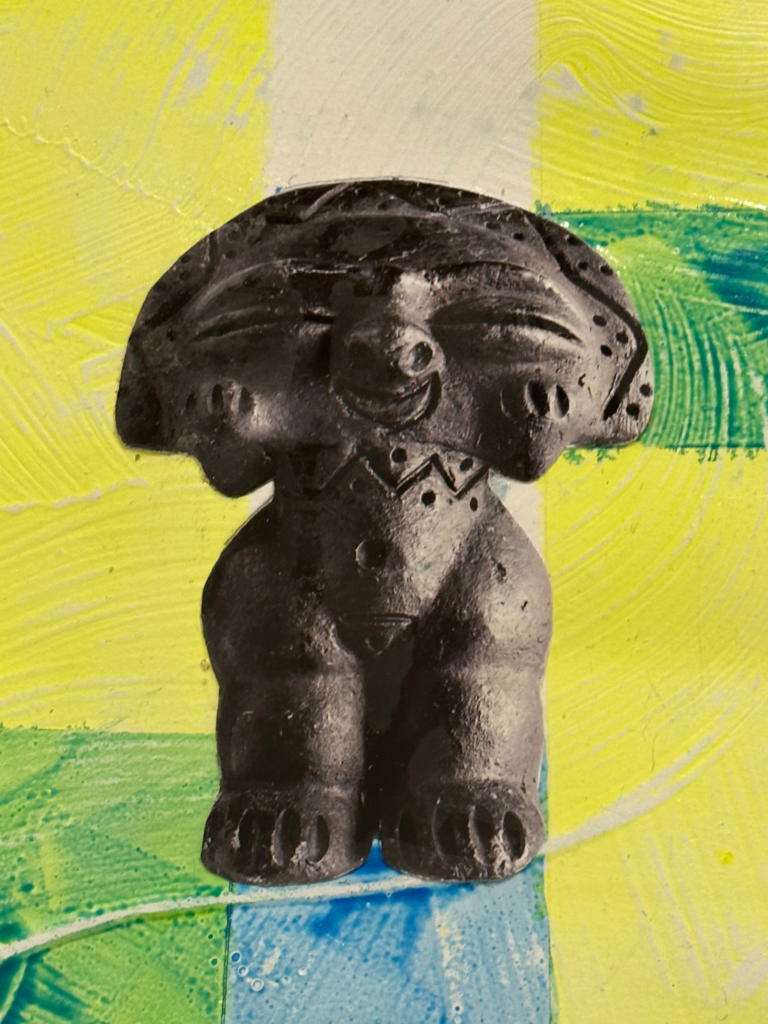

This goddess is portrayed with a largely humanistic form: it has two legs, two arms, and a torso. The head of the figure, however, is a half-circle that contains line work, dots, and formed features. The entity looks back at you with a smile so big that it closes the figure’s eyes. The creator may have given the sculpture a half-moon-shaped head to remind the viewer that they were worshipping the moon.

When researching, oral histories were central to understanding Taíno beliefs in the agency of this object. Diosa Luna, the Spanish name for the moon goddess, was understood to have the power to get women pregnant. One story proclaims that a woman became pregnant in her sleep after praying to the moon goddess. Thus, there is a close connection forged between fertility and the moon represented by this deity.

Double-headed eye goddess

The last figure that captivated me is the Double-Headed eye goddess from Cappadocia, Turkey, dating to the 3rd millennium BC. I find this deity interesting because when inspecting the object, it does not look like an ordinary sculpture of a goddess. However, this unusual shape is crucial to the spiritual power of the deity.

Within the Anatolian region, many sculptures were uncovered with this same imagery. However, none were identical; each object holds its own identity and imagery. Yet, scholars believe the figurines align with the Great Mother of the Gods. The Great Mother is an entity followed by Middle Eastern and Balkan Cultures, believed to grant fertility and prosperity. A woman who prayed to the Great Mother could be blessed with pregnancy and a healthy birth.

You may be asking, how do the Venus of Willendorf, Taíno goddess of the Moon, and the Double-Headed eye goddess represented in these collages connect to the rest of Las Hermanas Iglesias’ exhibition? The answer lies in one of the fundamental themes of the project: caregiving. Both of the artists experienced the journey of pregnancy and motherhood during the difficult times of the pandemic, when the connections between parenting and social issues such as labor, healthcare, childcare, and reproductive justice became increasingly clear. By connecting their personal experiences to the ancient cultural imagery represented in their artwork, Las Hermanas Iglesias place these contemporary conversations within a longer history of beliefs surrounding fertility and motherhood. These talismans represent not only fertility, but also the protective power of caregivers and their essential role within society.

Las Hermanas Iglesias is on view through July 9, 2023. Visit the exhibition page for more information about the show.