Austin In Depth

CHAPTER 4: Conceiving Austin: 1986–2015

Chapters

First conception: Cramer pavilion, 1986–89

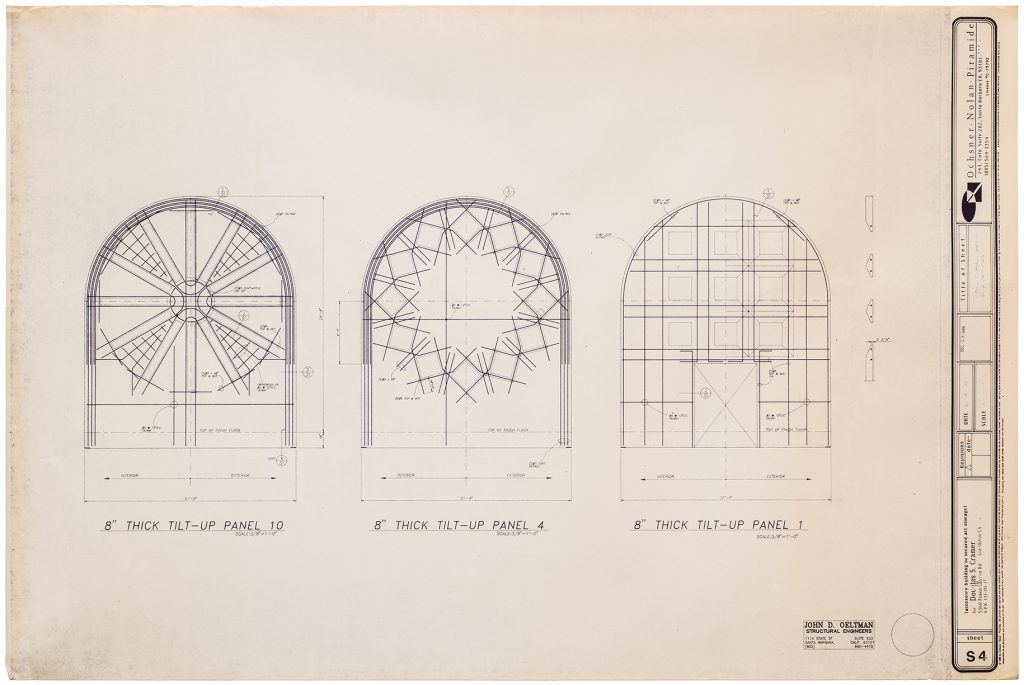

If the conceptual origin and artistic lineage of Austin belongs to the artist’s time in France and his love of Romanesque, Gothic, and Judeo-Christian artistic traditions, the start of its actual realization happened in California and Spencertown, New York, in the mid- to late 1980s. The prominent television producer and distinguished art collector Douglas S. Cramer had a vineyard in Santa Ynez, California, north of Santa Barbara, where the “Cramer chapel,” as Austin’s first iteration was labeled in blueprints, was to stand.[3] Cramer was an avid collector of Kelly’s work; his foundation, which helped to move the project along, was then based in North Hollywood. Cramer proposed the idea of an architectural pavilion in his vineyard to the artist, who readily took on the challenge. The original site was a sloping one overlooking vineyards, and would have been leveled off in the place where the building was to stand, as shown in a blueprint site study created at the time (figure 26). Between 1987 and 1989, the project was brought to a high level of design completion. The architect Tom Ochsner of Ochsner Nolan Piramide in Santa Barbara was engaged to translate Kelly’s vision into architectural plans.

Before that step, however, Kelly himself made a series of drawings and plans which carefully articulated his concepts. The first study, a small, simple graphite drawing, clearly shows all the basic elements in place (figure 27). But to convey his ideas precisely for the architect, he made a series of carefully measured technical drawings (click below to see slideshow):

In clear, diagrammatic fashion Kelly shows the scale he had in mind in an early hand-drawn study (figure 28). He numbered the walls of this simple plan, which, paired with a drawn section of the central arm, conveys the sizes of all of the walls and arches. Each facade is 20 feet wide; both transept arms and the half-dome arm are 20 feet in length and width; the central arm is slightly longer than the three others at 25 feet; the walls up to the spring of the arches are 14 feet, and each arch creates a 10-foot radius; the total height is 24 feet. All of these measurements are recorded in a series of sections and plans Kelly made with ruler and compass, coded with letters to show each facade, with the sizes of all the building’s segments and features indicated with measurements and arrows. While not an architect, Kelly knew precision and clarity was needed to translate his idea into a real building. For each of the stained-glass compositions, for example, he photocopied his graphite drawings and made detailed notations about measurements and color schemes (click below to see slideshow).

They reflect a fully fleshed out idea and contain all of the building’s defining features: a simple plan of two intersecting barrel vaults, forming a groin vault at the transept; an eastern-oriented half-dome terminating that end; and flat facades facing west, north, and south, each featuring striking stained-glass compositions under their arches.

These designs date to 1987 and closely reflect what the project was to become. The building’s form and stained-glass windows seem to have been there from the start. Other drawings show various concepts for the interior art. The Totem sculpture for the apse evolved, for example, (figure 29) from a bronze form with concave circle-segment sides to a soaring, wooden piece with concave sides forming a flare at the top; both are formal types of the Totem series explored and created by the artist in multiple works over time. Kelly also apparently considered a different configuration of the stained-glass windows as well: he tried the “starburst” spectrum on the entrance facade (figure 30). This particular design has a less harmonious relationship between the windows and the arch, filling the latter less fully than the final design; in the end, each of the circular window compositions is bisected by the spring point of each arch, its upper half fully filling its arch. The rectilinear grid in front is indeed better suited to the entryway because of the rectangle of the door and the need for more height to accommodate it. Such refinements are reflected in the blueprints that were drawn up by Ochsner Nolan Piramide design as the next step in the process (click below to see slideshow):

Other drawings from the same year reflect an evolution in the overall concept for the artworks inside. At first, the interior was to be simple and unadorned, save for the Totem sculpture. However, Kelly did not wish for the building to become a gallery for the work of other artists [4], so he starting thinking about what pieces of his might work in the space. Preliminary studies show two ideas for relief sculptures on the building’s walls, (figure 31, figure 32), as well as a concept for a painting conceived specifically for the structure (figure 33, figure 34). However, at some point that same year, Kelly had the idea to create fourteen sculptural relief panels in black and white, conceived as abstract versions of the Catholic iconography known as the Stations of the Cross. The artist had focused on a reductive black-and-white language in numerous works over the years, exploring in them nuances of visual weight and balance. [5] Though not religious, Kelly’s love of art history meant he was long familiar with Christian subject matter; years before he had made two drawings of scenes from the life of Christ, some of which overlap with traditional Stations of the Cross iconography, probably while visiting a church, during his time in France (figure 35). As he was looking to fill a building with a series of related works, adopting this subject made perfect sense because it would fill up the space with a holistic series. And there were two important, celebrated precedents of this subject in modern art: Henri Matisse’s chapel in Vence, France, and Barnett Newman’s iconic series of paintings now at the National Gallery, Washington, DC, both of which also used reductive black and white. Kelly’s original idea for the panels was to embed them into the walls of the building so that they were fully integrated into the structure, though he changed them into relief panels for Austin.

We can see the first complete representation of the final concept of the Cramer pavilion in two models made in the artist’s studio; these may predate the artist’s series of drawings. The first, which flattened out for mailing (figure 36), was sent to the architects, as one of their letters to Kelly suggests. [6] For the first time, a model allowed the artist to pull together all of the diverse elements he had so painstakingly measured and drawn individually into a cohesive, three-dimensional whole. Photographs taken of it set up at the time give a sense of scale using a human figure (figure 37). The windows were all rendered in watercolor, the relief panels represented by small versions in paper adhered to the walls in groups of twos (for the shorter transept arms) and threes (the longer walls of the nave). Kelly was now able to show how he conceived their placement and relationship to real, albeit miniature, space for the first time. A simple paper arch suggests the vaulted ceiling and frames the Totem, in this model still the earlier, convex form. A second model was created by Kelly and his studio out of foam board, with lighting gels used to achieve the effect of the stained-glass windows (figure 38). It is charmingly handmade but conveys the main design concepts beautifully.

This model, along with other designs and documentation, shows how far along this project was; the decision not to move forward came late and after the final design was largely complete. For example, in 1989, Kelly sent a letter to his fabricator Peter Carlson with a quick sketch of a square panel and an explanation of what he wanted: “Enclosed are the drawings for 14 pieces; the black should be granite or slate + the white should be ‘Thassos white’ – or whatever is the best white without streaks. The marble + granite/slate should be 3/4” thick.”[7] A large sketchbook dated 1989 records the designs for each of the panels with precise measurements and clear indications of how the blacks and whites were to be divided (click below to see slideshow):

Kelly held onto the foam board model and many who visited his studio saw it over the next twenty-five years or so. The artist kept hope that the project might find the right circumstances in which to be realized, his little model and all his drawings ready to be used when the time was right.

Sources and Inspiration

Austin has a chapel-like form but is meant to inspire through its art—Kelly conceived it specifically as non-denominational. Yet its architectural language and artwork stem directly from the artist’s experiences of churches, chapels, and cathedrals in Europe, particularly France, and especially those in the Romanesque style. It consists of two barrel vaults intersecting at right angles to create a groin vault, transept arms, with one arm terminating in a half-dome where the apse would normally be. Because the central space (which corresponds to a traditional nave), is the longest section, it makes what is known as a Latin cross plan. Though Austin is much simpler than the buildings that inspired it, with no divided interior spaces, the experience of visiting it is similar and intentionally like visiting a small Romanesque or Cistercian chapel. Romanesque architecture is partly characterized by its legible geometry, in which the interior spaces are readable in the exterior features. On the other hand, such buildings typically had pitched, trussed roofs covering interior vaulting, which is thus not visible on the outside. In that sense, Austin has more in common with certain modernist buildings, such as Louis Kahn’s Kimbell Art Museum in Fort Worth, Texas, which uses barrel vaults to such striking effect both inside and out. Two monuments of great inspiration to Kelly, the Abbey of Saint-Savin-sur-Gartempe in Poitou, France, and the Church of Notre-Dame la Grande in Poitiers, both feature massive barrel-vaulted naves and numerous groin-vaulted side chapels (figure 39, figure 40). They must have been at the forefront of his mind when he designed the Cramer pavilion.

What Kelly created in Austin is not an imitation of a Romanesque chapel, but rather his distilled version of the experience of visiting such a building. A visitor immediately feels the focus on the end of the main aisle on entering, dominated as it is by the wooden Totem. That work is itself a material and formal allusion to the cross normally placed at this spot in a church. The very nature of a longitudinal church nave imparts a sense of procession toward the opposite end, even on a relatively modest scale. In most churches, this is counteracted by interior richness, which encourages meandering along the perimeter into interior chapels and their attendant decorations. For Austin, Kelly’s fourteen relief panels distributed around the walls have a similar function and create an ordered, serial viewing experience.

Though they are totally abstract, the artist conceived his panels as Stations of the Cross, a common Catholic narrative of Christ’s last day on earth told in a set series of scenes. In 1949, Kelly had made two schematic drawings related to the life of Christ, around the time he’d been working on paintings of the subject (figure 41, figure 35). He returned to the idea for the Cramer pavilion in 1986, trying a version of the Stations with curved forms (figure 42) before settling on a different version with straight lines only. This version is reflected in a beautiful sheet showing all the forms in three rows, the connection to the iconography spelled out by the artist (figure 43). As reductive as they are, Kelly’s Stations are an astute adaptation of the subject through the purest of formal means.[8] The long line of the cross itself and its positioning in specific scenes as Christ carries it had a major role in the visual traditions of this subject. It plays out here in the verticals, horizontals, and diagonals that give the panels their flow across the space: a simple line formed by black and white is Kelly’s allusion to the cross’s longitudinal form. The artist also uses black and white symbolically, to represent death and resurrection, in the last three panels. A study in which he treated the totality of the panels on one sheet gives a powerful sense of the overall rhythm of the series and their specific order.

The one motif in Austin that Kelly did not invent himself is the composition of the east windows, one he described as “tumbling squares.” It was directly inspired by the rose window on the North facade of the Cathedral of Notre-Dame de Chartres in Chartres, France (figure 44). The artist first visited this celebrated Gothic monument during his spring 1949 tour around the country to see sites of interest. He described his impression of this window years later:

The north transept of Chartres, the stained glass, has twelve diamonds. When I first saw it in ’49, I said, “How can twelfth-century someone do that? To make it tumble? They look like they’re moving.” And so, I worked it out—how they had formed it. Because all the points all pointed toward the center . . . that was something that occupied my mind for a long time.[9]

In this iconic work of stained glass, the diamonds that caught Kelly’s eye are part of a much more complicated composition that fills a huge wall rich with biblical imagery. The north rose window represents the Glorification of the Virgin; its twelve diamonds depict the Old Testament Kings of Judah. The window’s complex geometry is supported by the stonework tracery holding it all in place, and this is in fact what creates the bold shapes noticed by Kelly. In Austin, their bold and dynamic geometry comes thrillingly to the fore, extracted and distilled to create a new form of stained glass.

_____________________________________________________

[3] Louise Berkinow, “La Quinta Norte Douglas S. Cramer’s Ranch in the Santa Ynez Valley,” Architectural Digest, April 1987, 136-47.

[4] Jack Shear, interview with author, September 5, 2017.

[5] “Black and White” was in fact the subject of a major Kelly exhibition in 2012, see Ellsworth Kelly: Black and White, ed. Ulrich Wilmes (Ostfildern: Hatje Cantz, 2012).

[6] Kelly Studio archive, Spencertown, New York.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Carter E. Foster, “Stations of the Cross: Black, White, Light” in Ellsworth Kelly: Black and White, ed. Ulrich Wilmes (Ostfildern: Hatje Cantz, 2012), 34-47.

[9] Ellsworth Kelly, Ellsworth Kelly: Fragments, directed by Edgar B. Howard, and Tom Piper (New York: Checkerboard Film Foundation, 2007), documentary film. Quote starts at 52:40; transcription here by author.

IMAGE CREDIT: Blueprint of “Cramer chapel,” by the architectural firm Oschner Nolan Piramide, 1989. Photo courtesy Blanton Museum of Art, The University of Texas at Austin.