If the Sky Were Orange: Art in the Time of Climate Change

Part Two – Paper Vault

“The past throws light on the future, and the future throws light on the past.”

Edward Hallet Carr, from”What is History?”

The story of climate change is the story of our time. But it is not a story that started with us. It started, arguably, when our human ancestors discovered the usefulness of fire and began clearing land for agriculture, which began to have an impact on the chemistry of the Earth’s atmosphere. The story picked up momentum during the Industrial Revolution in the 18th and 19th centuries, which was powered by fossil fuels – oil, coal, and natural gas — which release heat-trapping carbon dioxide into the atmosphere when they are burned. And the narrative reached a dramatic crescendo in the late 20th century as fossil fuel emissions rose with the development of our modern world and the scale and complexity of maintaining a hospitable planet that is home to eight billion people became clear.

In Part Two of the show, I use works of art from the Blanton’s permanent collection to reflect on the story of climate change. Most of these works do not address climate change directly, but it’s there nevertheless–you can see it in the way these works define our relationship with nature, technology, energy, and political power. I invite you to read through these sections, exploring all the featured works, and think about what these artists are telling us about how we live and what kind of future we are creating for ourselves–as well as for every other living thing on Earth.

Idealized Nature

In art and mythology, the natural world has long been a place where gods roamed, where mystery and beauty lurk behind the thin sheen of everyday life. Most of all, it was a realm that, until the twentieth century, was a place that was beyond human touch or control. Chang Dai-Chien’s Cinnabar Lotus is a wonderful example of this, with its asymmetrical forms hinting at nature’s deeper beauty. But domination of nature has also been a subtext in Western art–the very impulse to create art is, in its way, a subjugation of nature. Claude Lorrain’s Pastoral Landscape is an idyllic vision of humans’ relationship with nature, both orderly and completely artificial. In the painting, the house seems to grow out of the rock itself, as if Lorrain were trying to fuse civilization with nature in what some critics have called “an ideal landscape.”

The Romance of Energy

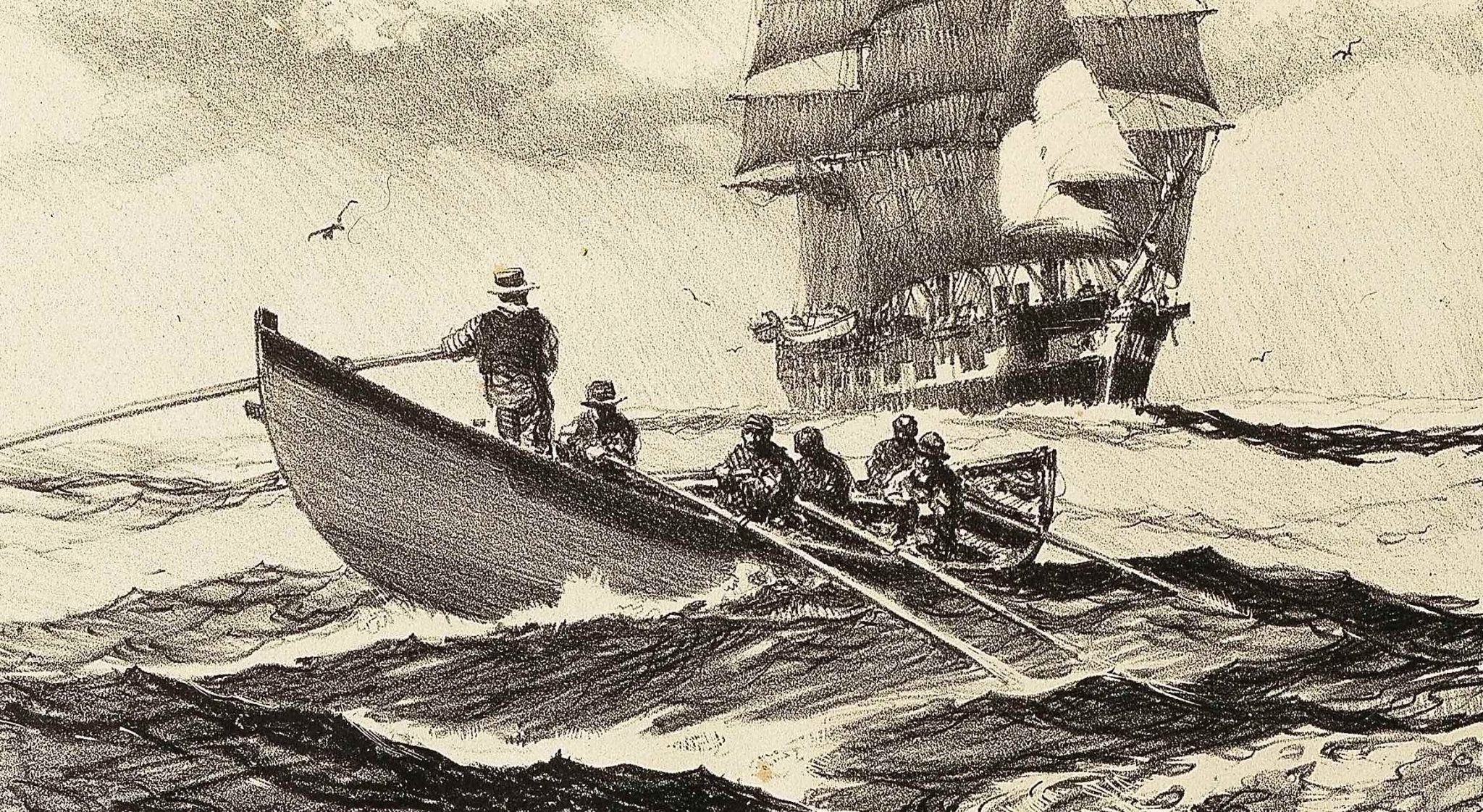

In the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, the quest for energy transformed our relationship with nature. Whether it was hunting for whales in the Atlantic (whale blubber was boiled to render oil for illumination and lubrication) or wildcatting for oil and gas in Texas, great fortunes piled up and new industries were born. Giuseppe Bernardino Bison’s Landscape with a Watermill offers a gentle perspective on industrialization, integrating technology with a pastoral vision of nature, as if to suggest the two could co-exist in easy harmony. In James Brooks Oil Well at Sunset, the orange glow of the setting sun gives the angular oil rig and nearby structures a romance that is somewhere between sublime and apocalyptic. Jerry Bywater’s Oil Field Girls contrasts the sensuality of the human form with a backdrop of oil rigs, piles of old car tires, and a sky filled with ominous black smoke.

The Age of Abundance

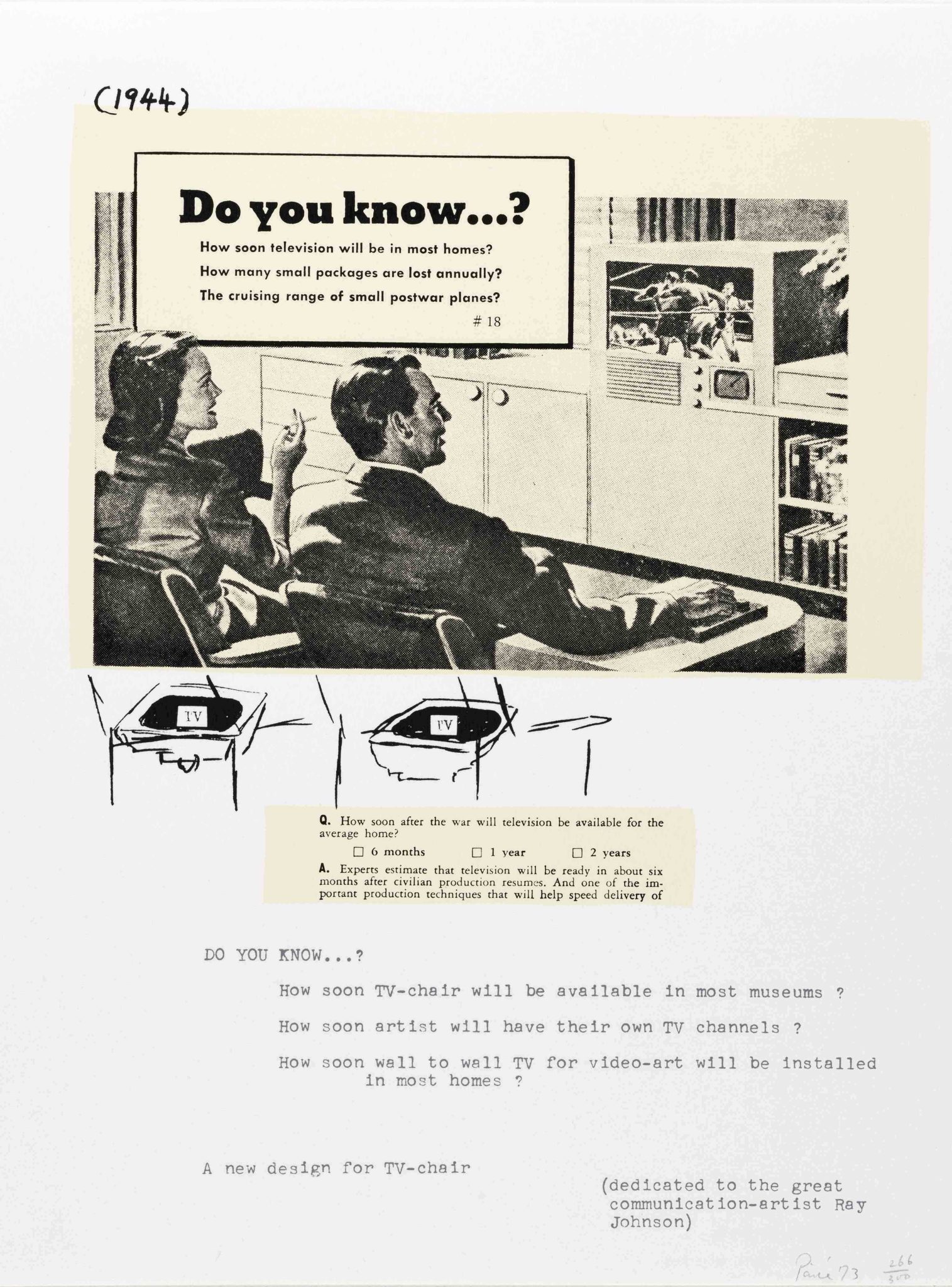

During the post-World War II boom, fossil fuels powered the rise of a new economy, and a new vision of the good life–suburbs, shopping malls, highways, inexpensive airline travel. In Vernon Fisher’s cartoonish Man Cutting Globe, a clean-cut man in a white shirt and tie–he looks like he just arrived home from his job at an advertising agency–cheerfully carves up the Earth while a young boy looks on. Nam June Paik’s Untitled, from the New York Collection for Stockholm captures a similar post-World War II exuberance and promise of technology that will make life better, more comfortable, and more entertaining. In Andy Warhol’s famous Onion Soup, the packaging and commoditization of a common vegetable has severed it from the natural world (it’s impossible to look at Warhol’s soup can and imagine an actual onion growing in the soil somewhere). In Jacques Callot’s Avaritia [Greed] and Gula [Gluttony], humans are corrupted by winged devils–an echo of the religious idea that the worst aspects of human nature are have empowered by forces beyond our control.

Power, Money, and Activism

In 1968, Apollo 8 astronaut Bill Anders snapped a photo of Earth from lunar orbit–the picture, known as “Earthrise,” was the first view of our planet from space, showing it as a pale blue dot in the vast blackness of the universe. The photo changed how many people see themselves in the universe, and is often cited as the beginning of the modern environmental movement. It was part of a broader social upheaval that artists responded to, driven by everything from protests against the Vietnam War in the 1970s to the AIDS epidemic in the 1980s. A powerful example: Donald Moffett’s He Kills Me, created during the AIDS epidemic when President Ronald Reagan was emblematic of indifference to the suffering of others unlike oneself, captures the distance between the powerful and the doomed.

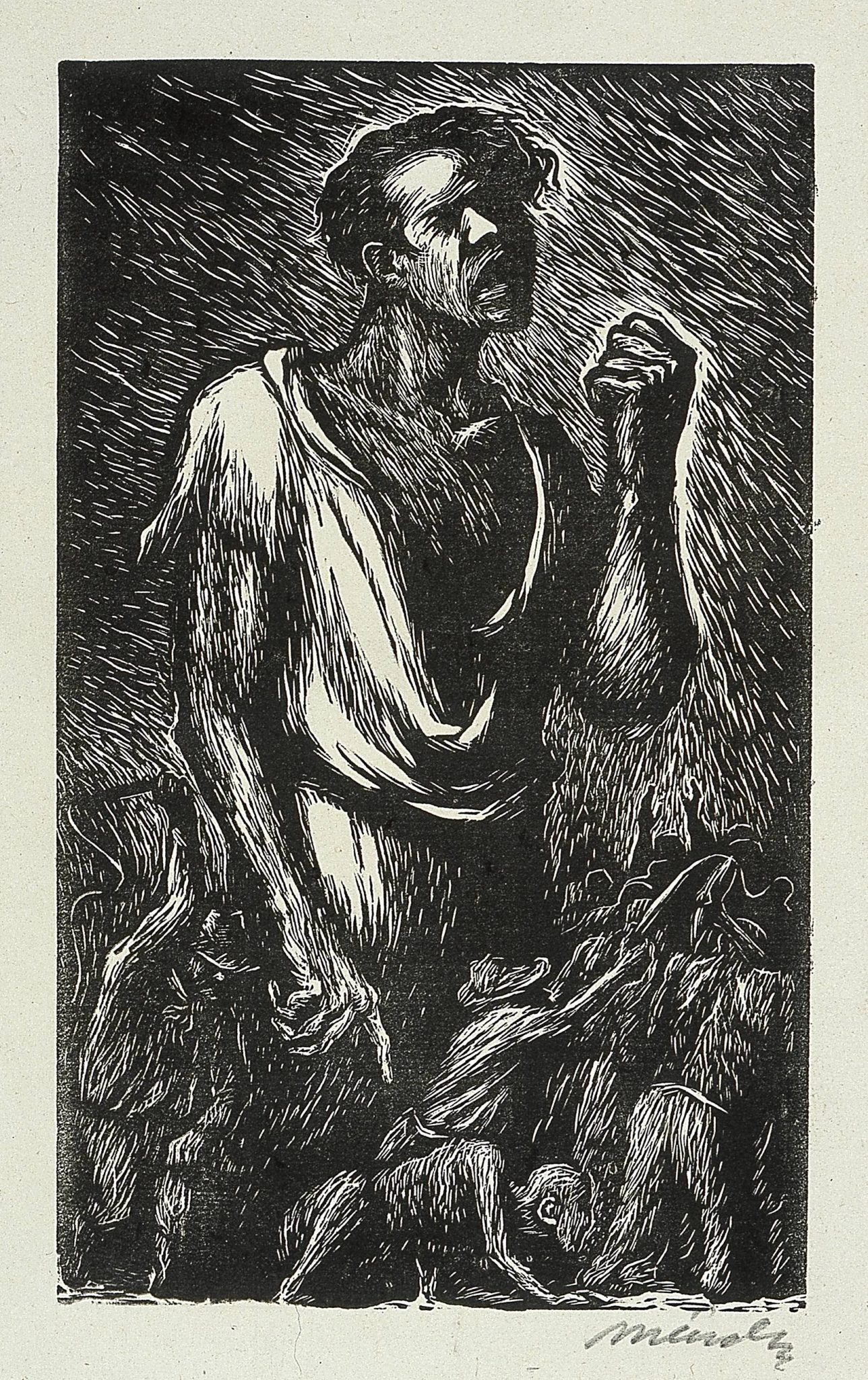

Other works in this section explore the tension between progress and profit. Peter Saul’s World of America Number One, features a giant red dollar sign that towers out of the Earth, surrounded by an electric yellow glow, as if the dollar sign were a plug that charges the world. Martin Phillip Duranzo’s General Electric, shows a bright, happy still life with tulips and dollar signs filling the air and the GE logo like the sun in the blue sky. Kim Jones’ Untitled, showcases a giant naked Shiva-like figure tangled in a mess of power lines, making the conflict between spiritual life and industrialism clear. Leopoldo Mendez’s Protesta, shows a worker with a fist raised high above others who are being beaten and whipped, holding an elemental grace that speaks for the exploitation of workers and the brutality of unfettered capitalism.

Consequences

One of the lessons of the twentieth century is that humans do have the power to change the world—and not always for the good. Rachel Carson’s book Silent Spring illustrated the damage caused by the indiscriminate use of pesticides by imagining a spring day without birds. In the 1970s, scientist James Lovelock introduced the Gaia hypothesis (named after Gaia, the goddess of the Earth in Greek mythology), which conceptualized Earth as a living organism, and one that human activity threatened to throw out of balance. By the 1980s, the basic facts of climate change—namely that the burning of fossil fuels was heating up the planet threatening to destabilize the familiar, hospitable climate on which all life is dependent—became well-established among scientists. The question then became, what are we going to do about it?

Nic Nicosia’s Near (modern) Disaster #8 brilliantly mocks our understanding of the power of nature with kids dressed like J. Crew catalog models pretending to be caught in a fierce storm. Robert Cottingham’s Hot takes the single word that best describes what the burning of fossil fuels is doing to our climate and shows you the available ambiguity—is it referring to “hot” food, a “hot” date, or a “hot” planet? Joel Sternfeld’s After a Flash Flood, Rancho Mirage California, a work from 1979, reads today like a visual parable of the climate crisis, with a sharp line between those whose lives are destroyed by it and those who carry on as if nothing were happening.

The Great Rearrangement

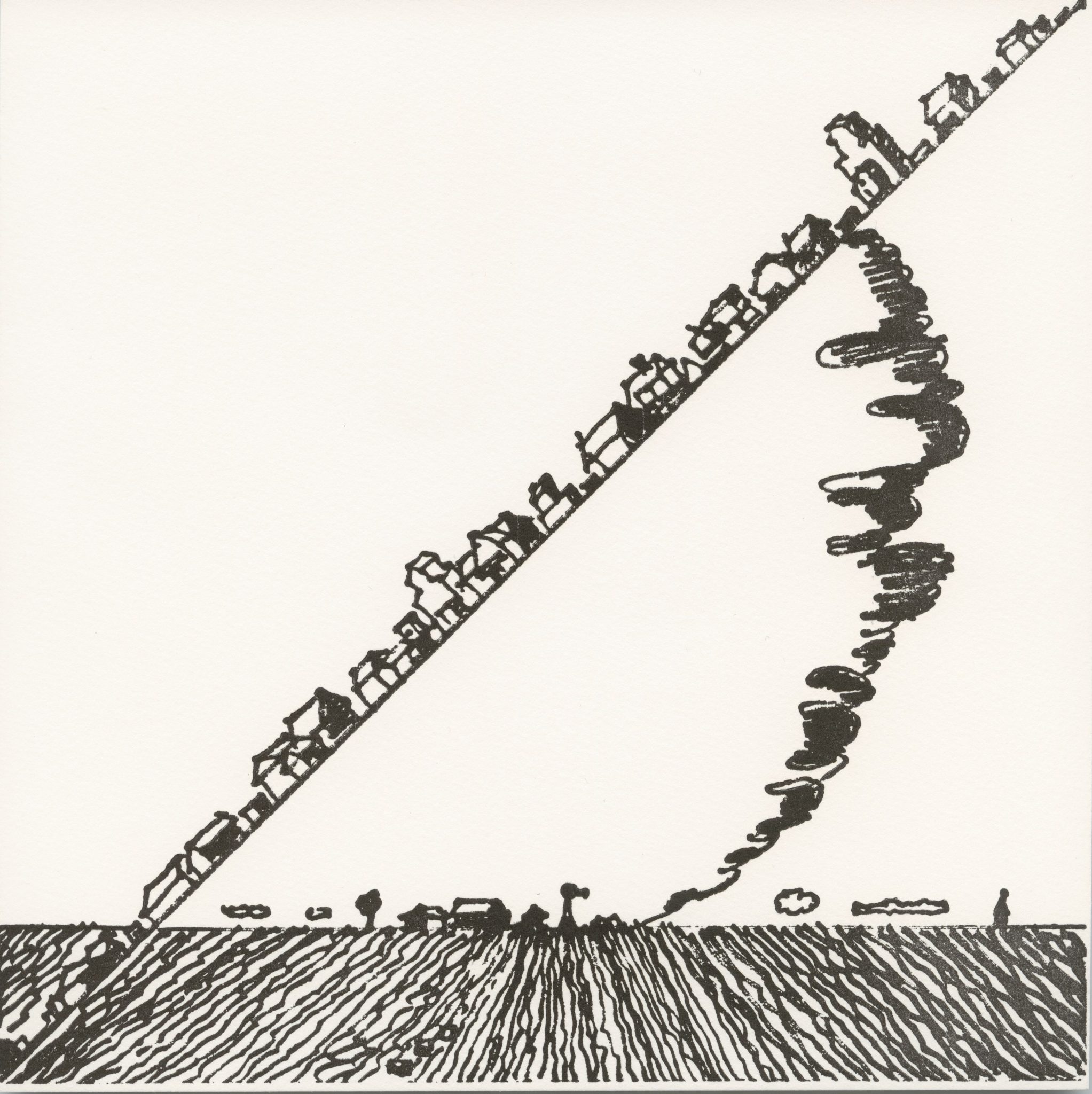

As the world heats up, boundaries change: glaciers melt, seas rise, droughts linger, plants and animals migrate, seeking out their ‘Goldilocks Zone’—where it is not too hot, not too cold, just right. Joe Zucker’s The Relocation of Property by Natural Forces may have been created with earthquakes or tornadoes in mind, but it captures something of the scale and suddenness of a world that is being rearranged by climate change. In Luis Jiménez Study for Border Crossing (Cruzando el Río Bravo), the ancient movement of people fleeing war or famine is given a glossy, modern sheen that is perfectly appropriate for the Climate Age, when increasingly intense droughts and heatwaves force people to move to more hospitable places.

Bounty of Nature

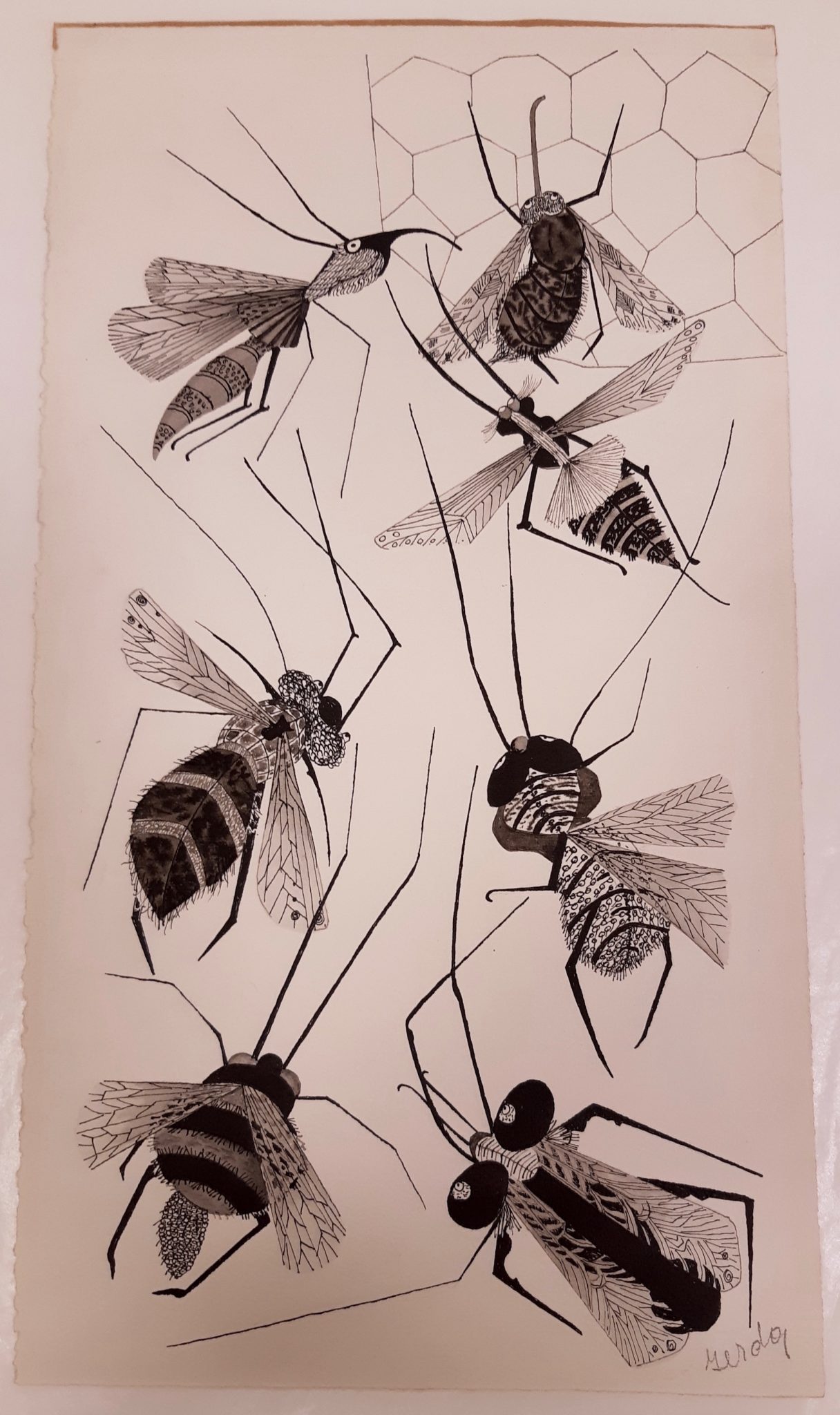

Save the planet, climate activists often say. In fact, the planet will be fine. It’s life as we know it, which is finely tuned to the stable, gentle climate that has existed for the past several hundred thousand years, that is at risk. In this context, awareness of climate change pushes us to think differently about our place in the natural world and about our relationships with other living creatures. In Tail Count, from Catfish Press Exchange, Cynthia Osborne imagines 15 whale tails waving to us, as if they were part of a secret dance that we are lucky enough to catch a glimpse. Gerda Brentani’s Insectos [Insects], arranges insects like costumed characters waiting to go onstage in a Broadway show—you can almost feel their excitement as they wait for the curtain to rise. Finally, Ben Shahn’s Adam and Eve, with its simple, child-like rendering of a naked man and woman holding hands, reminds us of the fundamental force of nature that has always been and will always be our best hope for a better world: love.

Feature Image Credit: Gordon Hope, The Whale Hunt (detail), not dated, lithograph, 8 15/16 x 9 13/16 in., Blanton Museum of Art, The University of Texas at Austin, Gift of R.D. Woods, 1984