Off the Walls: Gifts from Professor John A. Robertson

CHAPTER 3: Jonathan Bober, “Tribute to a Friend-Collector”

Chapters

“Tribute to a Friend-Collector”

Jonathan Bober

Andrew W. Mellon Senior Curator of Prints and Drawings

National Gallery of Art, Washington

John Robertson was curious, about everything it seemed. His range was striking, his knowledge extraordinary and often dauntingly precise in a host of areas. There was of course the law and his internationally recognized expertise in reproductive rights and ethics, which began to extend to genetic engineering. But his grasp of politics, from local to national, seemed just as great. Talking basketball, college and professional, he could have held his own in the most fanatical sports bar. His dedication to many forms of culture was just as genuine and deep. An avid reader of all forms and genres, John could parse new novels and quote lines from favorite poems. His appetite for film of almost every kind, classic Hollywood to smallest independent foray and documentary, was voracious. He listened to music constantly, enjoying the local scene, but following jazz seriously—from the major names to the outer fringes––live whenever possible and through stacks of compact discs. And of course, the visual arts. John missed few gallery openings of any kind in Austin. He would accept professional invitations to see exhibitions and attend contemporary fairs in other cities. He would acquire whatever initially intrigued him and, more importantly, seemed likely to sustain his interest.

John’s pursuits were even more striking in character. His energy was boyish. His openness to new experience, a striking unguardedness, and an essential modesty were that of an adolescent. His critical awareness and especially his instinct for authenticity in expression of any kind was that of an unusually textured mind and naturally refined sensibility. These meant that John would choose, assess, and embrace fundamentally on his own terms. He might canvas the opinions of others, but out of the same curiosity, never as guide or determination. He would read the pertinent critical literature and reviews, but after the fact of his own reckoning. In all matters, his judgment seemed world-wise, acute but balanced, moral but generous. Exercising that judgment, wrestling with the challenges of ambiguity and uncertainty, was evidently its own source of great satisfaction and pleasure. His gravitation to subjects and forms of least definition or prescription, from the creation of human life to the representation of the modern condition, was inevitable.

Curious above all about other persons, their personalities, and the exchanges he might have with them, John was drawn first to the works of artists in his own settings. While in his first position, at the University of Wisconsin–Madison, his contact with its noted art faculty and their accomplished printmaking prompted his first acquisitions. His interest in the medium––the fascination of its processes but especially the collectivity of its production and the implied community of its reception––remained paramount. The transition to Austin’s culture was in this sense effortless. The printmaking program at The University was at its most vital, with masters of the major techniques on faculty, often brilliant students, and an ancillary program that invited artists unfamiliar with the medium to participate. John delighted in the richness of a source so close to home. This was the origin of a good number of the works––Bob Levers, Bill Lundberg, Peter Saul, Lance Letscher, Michael Ray Charles––that have come to the Blanton. By extension, he was enthusiastic about contemporary Texas artists like Randy Twaddle and Vernon Fisher, but no less about a major figure of an earlier generation, Dorothy Hood.

Conspicuous in a number of these regionally based (if hardly limited) works is the kind of subject that most engaged John. Imagery of social commentary, caricature, and overt satire represented a common ground for his range of interests and an expression of his progressive political concerns. John found the vulnerability and gravity of Glenn Ligon’s untitled 1992 etching irresistible and acquired it upon release, just as the artist was coming to prominence. He was enthusiastic about Sue Coe’s dark critiques of unjust order and destructive habit. But more often he was drawn to figurative social imagery with a humorous or playful dimension. He delighted in Peter Saul’s deliberate, boisterous offenses against good taste. For several years he sought a Cindy Sherman that would resonate for a lower middle-class boy from South Jersey (a readily admitted self-description). Not all works of this kind did. John bought Vito Acconci’s Wav(er)ing Flag only to decide its size was too cumbersome and its conceit too obvious. Philip Guston was John’s absolute favorite among major names for the gentler irony and unassuming hand in his heaped detritus. Throughout such imagery, John took special delight in language and its own ironic quotient. He would repeat certain works’ titles—Levers’s Doin’ the Terrorist Strut Again, or Charles’s BLACK CATS GO OFF—with a smile at the disturbing made cadent and witty.

The greatest proof of John’s intellectual range and refined sensibility was his equal fascination with works of pure abstraction. In its vague reference to natural processes and vigorous hand, Terry Winters’s Clocks and Clouds is probably easiest to reconcile with other interests and the style of some of the Texas works. Arnulf Rainer’s drypoint, with its obliterated drawing, liminal shape, and shrill color, suggests game and irreverence that enthralled John apart from its striking visual appeal. But what of the pure geometry, subtle manipulation, and delicate inscription of Robert Mangold’s series of screenprints? Or the meditative evolution and fluid circulation in what was perhaps John’s proudest acquisition, Brice Marden’s Suzhou series? Or an unrelieved field of ink imparting kinesthetic sensation in Richard Serra’s Hreppholar V? In each of these cases, John had looked and deliberated—about Rainer for months, Mangold and Marden for years—before concluding the right stage of development and edition. The choice of work was then equally careful. Rainer’s Grünes Kreuz IV was one of a good half-dozen possibilities of different shapes and dramatically different inks. With the Mangold and Marden series, the question was whether a single sheet, a pair to imply extension, or the complete set. Only after days of looking, discussing, and reflecting was John satisfied that he understood enough of the artist’s intention to decide what best fulfilled it. (Sugimoto’s photographs, bequeathed to the Harry Ransom Center, were another such case.) If human affairs and social conscience anchor John’s collection at one end, pure form and aesthetic pleasure do at the other.

I met John in late 1987, in my third or fourth month at what was then the Archer M.

Huntington Art Gallery. It was tense. John had invited Hiram Butler, preeminent contemporary dealer in Houston and a brilliant impresario, to show him recent works in the print room. I had had no previous contact with either and felt it an imposition. They both became my dear friends. Hiram would be instrumental in some of the museum’s most important contemporary acquisitions over the next two decades, including James Turrell’s First Light, Carroll Dunham’s Red Shift, and Vik Muniz’s Jorge, and would encourage any number of gifts and contributions to other projects. John sought my opinion about nearly every acquisition he made, but as part of a continuous and confidential exchange about all of our shared interests. His direct support of the museum and its collections was modest. Seldom in the same twenty years did we talk about the destination of his collection. The possibilities were clear: his alma mater, Dartmouth, Wisconsin, and the Blanton. Only after John’s illness had advanced, and I had come to Washington, did the matter press. We had several conversations by phone and, after John’s recovery from lung transplant, one long lunch at the National Gallery––the last time I would see him. The Gallery had become another possibility. We agreed, however, that he had made his career and life in Austin. Our friendship had unfolded there. He had already given several works to the Blanton and arranged the acquisition of Lundberg’s Swimmer in memory of his beloved wife, Carlota. The rest of the collection belonged on campus, where it could help inspire and shape as surely as his teaching had. For me, it properly concludes a significant personal relationship to know that it is there and, with this exhibition, John is being recognized.

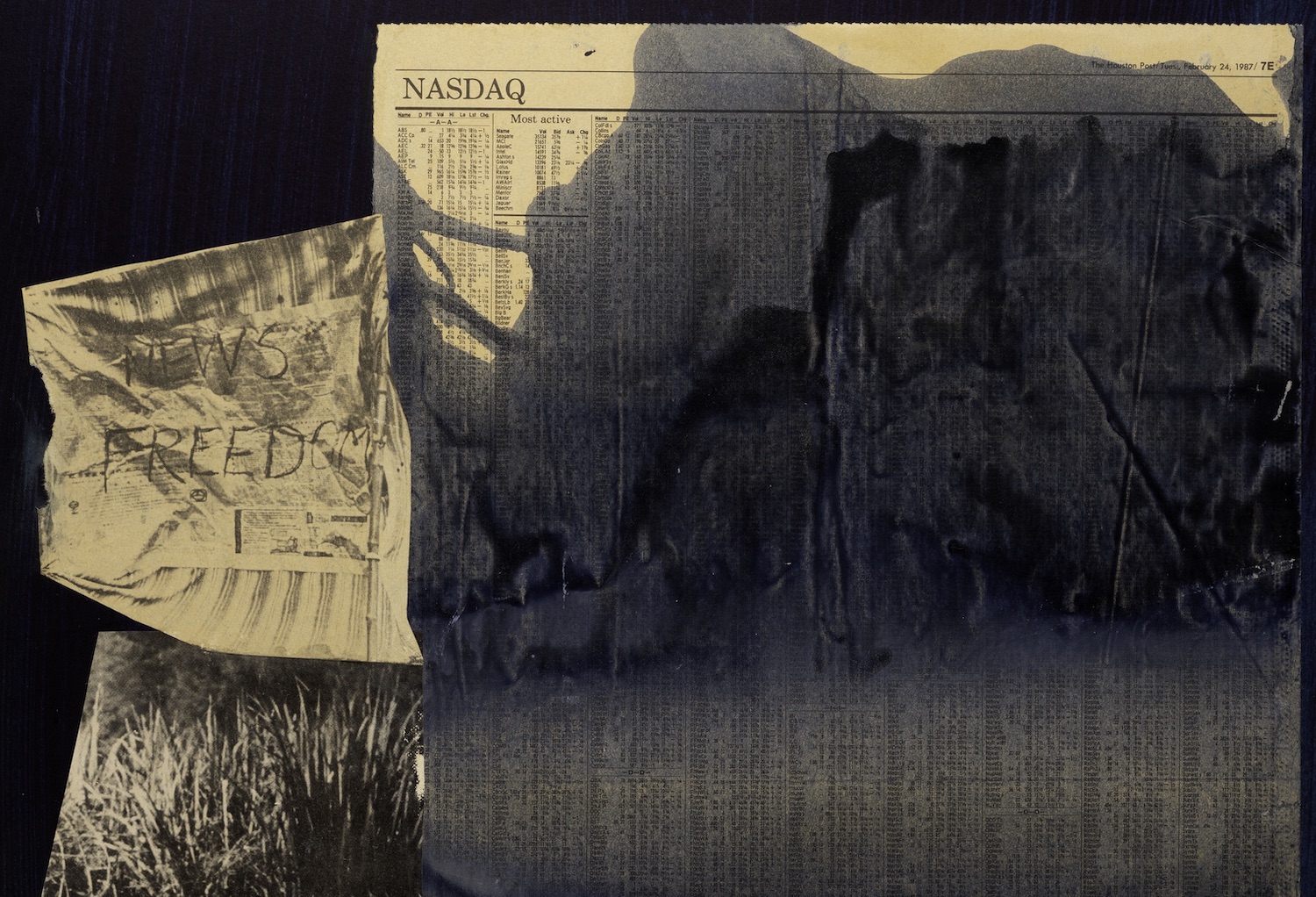

Image Credit: Dorothy Hood, Blade Skeins, 1987, collage, 30 x 20 in., Blanton Museum of Art, The University of Texas at Austin, Bequest of John A. Robertson, 2018