Off the Walls: Gifts from Professor John A. Robertson

CHAPTER 2: Richard Shiff, “Art and John Robertson”

Chapters

“Art and John Robertson”

Richard Shiff

Effie Marie Cain Regents Chair in Art

The University of Texas at Austin

Curiosity motivated John Robertson. Diverse forms of cultural achievement attracted his interest, and he never stopped learning. Professionally, Robertson explored the logic, practicality, and humanity of those parts of the American and international legal structure that pertain to rights associated with human reproduction. His scholarly work in the area of bioethics amounted to a public service, a source of guidance for legislators as well as for individuals facing difficult personal decisions. His publications continue to be widely read and cited.

Robertson’s academic involvement with the law demanded the most nuanced kind of reasoning. But the foundation of his legal work was human feeling—a sensitivity to human needs that guided the course of his logic. It’s not surprising that the type of legal scholar that Robertson became would have developed an interest in the arts, where the less rational but no less powerful areas of human achievement are found. The law and the arts as Robertson knew them were united by a sense of the ethical—by experience filtered through human emotion, acknowledging fundamental human needs. Art enriched Robertson’s intellectual and moral life as much as it enhanced his aesthetic life. His ability to perceive the connections made him a brilliant private collector of art, despite being a person of relatively modest means.

A collector with limited financial resources cannot afford mistakes in judgment. Robertson had a deep well of intuition, which he drew from and trusted. And he had prescience. He recognized artists of extraordinary quality who were either underestimated in the marketplace or at too early a stage of their career to have reached prices that could be afforded only by institutions with magnanimous donors or by individuals with extensive private resources. Many of the works that Robertson purchased decades ago would have been well beyond his means in his later years because they rose so much in value during his lifetime, as the artists who had caught his attention gained general recognition. In this respect, Robertson resembles the legendary early collectors of Minimalist art, Herbert and Dorothy Vogel, as well as Leo Steinberg, whose collections are now at the Blanton, along with Robertson’s. Beginning as a modest but avid collector and an engaged viewer of virtually every art exhibition on the UT campus, Robertson, by the end of his life, had become one of the Blanton’s significant donors. The collection he willed to the museum adds a remarkable range of objects to its holdings—a source of aesthetic experience to be savored by successive generations in the future.

* * *

I arrived in Austin in 1989 and soon became acquainted with John Robertson, who hardly ever failed to attend an art event in the city. He knew everyone. He was extremely affable, and we enjoyed long conversations about contemporary art. John liked to ask questions; perhaps this stemmed from his habits of mind as a law professor and supervisor of students. His questions were often challenging, even aggressively so, though always addressed with a wry smile. His inquiries concerned fine points of aesthetic appreciation, elusive matters of interpretation, and the mysteries of art market fluctuation. But I never had the impression that John needed any answers from me; I felt that he had all the answers he needed already. Wherever he did not, he was perfectly capable of figuring things out on his own. With all his questioning, I think he was assessing the general culture of art of which I was a part, and he was gaining an overview suited to his purposes. When he asked my opinion of this or that artist, I wasn’t acting as a consultant to him. He already had made intuitive judgments that he would rely on. In the spirit of broadening his understanding, he was looking for a counterargument or an interesting variation on what he believed to be the case. Talking about art, debating the value of various contemporary modes—for John, all this was informal research. Despite being knowledgeable, he was learning.

John introduced me to a number of local artists of great interest—he was my Austin mentor on the spot. He was well acquainted with everything happening in Austin’s art world as well as with activity across the state. He recognized the talents of Terry Allen, Vernon Fisher, Dorothy Hood, Luis Jiménez, Lance Letscher, and Randy Twaddle. John was especially involved with the work of the UT faculty in the programs in Fine Arts; he acquired art by Sarah Canright, Michael Ray Charles, Robert Levers, Bill Lundberg, Peter Saul, and Carolee Schneemann.

John Robertson was an eclectic collector. He avoided setting standards, rules, or principles in advance; his only inviolable guide to his activity as a collector was his interest. The work had to appeal to him. Usually, I think, the appeal was sensory and emotional, but it also had an intellectual edge to it; John extracted concepts and beliefs from the sensory array that visual art offered. He grasped the intelligence of art.

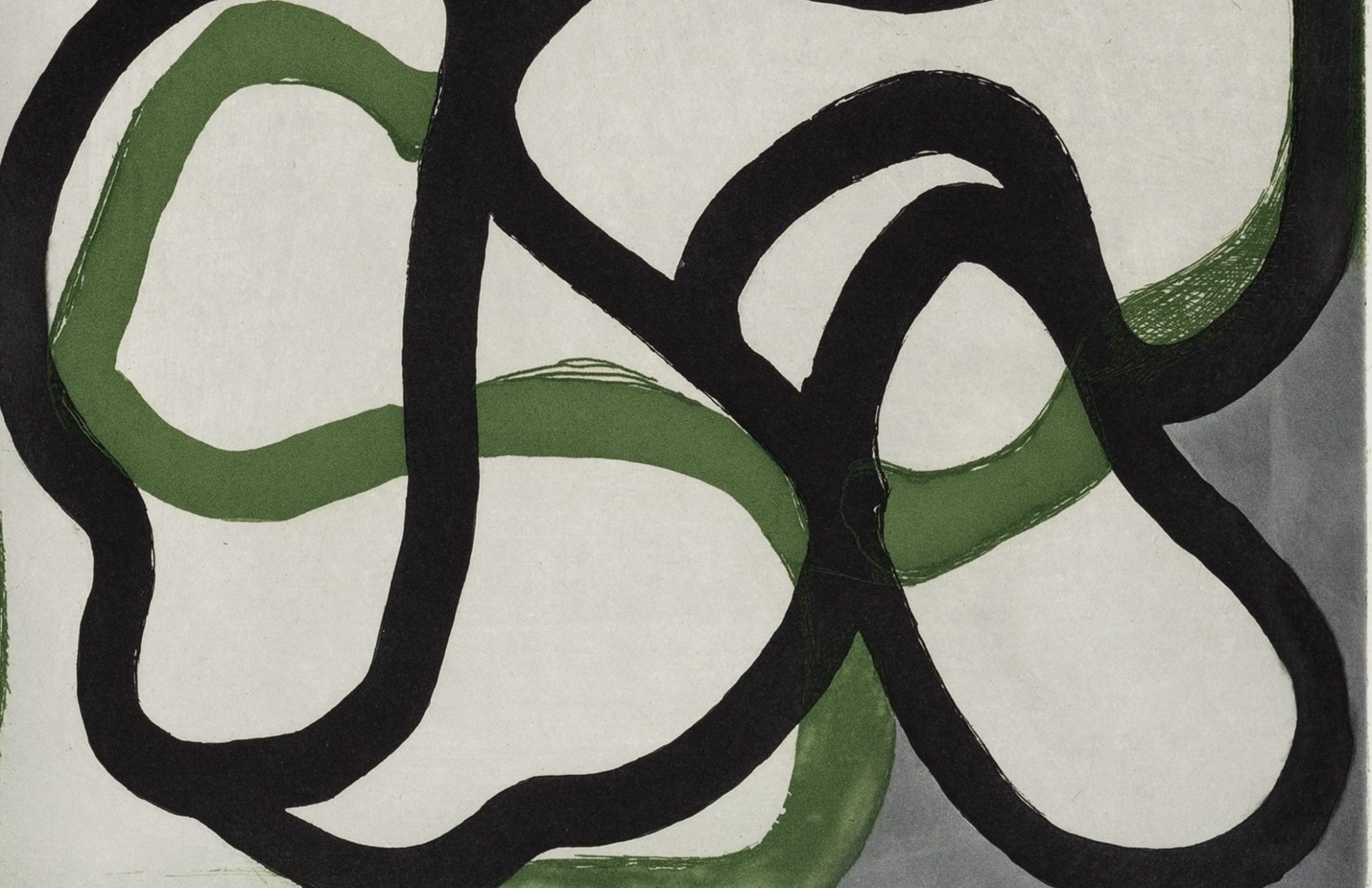

John had an instinctive attraction to the most challenging examples of abstract art (Robert Mangold, Brice Marden, Richard Serra, Terry Winters), yet he took delight in representational practices (Philip Guston, Peter Saul, Carolee Schneemann, Cindy Sherman). I doubt that John made much of a distinction between these two monstrous, often misleading categories, the abstract and the representational, any more than he would distinguish between works by male artists and those by female artists. He felt good about having a significant number of works by women and people of color in his collection, but this wasn’t what made the art good or appealing to him. The significance of a work—its sensory and moral strength—existed beyond the reach of our various categories and identities. John acquired examples of Sue Coe’s art of political activism, too strident for some viewers. And he acquired Vito Acconci’s Wav(er)ing Flag, a perceptual and conceptual puzzle with ambiguous political overtones—for some, not strident enough.

John’s examples of Guston’s representational art verges on abstraction, as if the “pile up” of the title were of tubular forms rather than animated limbs. His examples of abstraction from Marden verges on representation, for Marden’s lines recall the scholar’s rocks that inspired this period of his work. Just as John observed no strict division between the abstract and the representational, he was utterly flexible in his appreciation of media. Primarily a collector of graphic prints, photographic prints, and other works on paper, he also collected examples of film and video (photography as sculpture, so to speak). And when I visited him, along with the works on the walls, he enthusiastically guided me through the sculptural objects that punctuated the space of his living room. His beautifully simple, modernist house existed for the art within it.

I mentioned that John Robertson was prescient. He immediately perceived how Glenn Ligon’s art interwove the symbolic forces of literary text and graphic tone (blackness against a white ground). Ligon was still quite early in his career when he created the text-based print that John soon purchased—perhaps better considered as a pictorial representation of text, text rendered emphatically visual. This work quickly became celebrated as a powerful example of an African American artist exploring the implications of his identity within American culture. The text itself says a lot—“I feel most colored when I am thrown against a sharp white background”—but the presentation of the text, becoming indecipherable as it repeats within an increasing spread of blackness, says yet more. Perhaps it was his legal acumen that caused John to recognize the multifaceted brilliance of Ligon’s work, so rich in its conceptualization, and to bring it into his collection. I think there was more going on, that John responded emotionally to the array of thought and feeling that Ligon’s visualization presented. Here, as so often, art provided John Robertson, the distinguished scholar of law, with elements of emotional understanding that informed his professional work while subtly enriching every aspect of his daily life.

Image Credit: Brice Marden, Suzhou I, (detail) 1996–1998, color etching with aquatint, drypoint, and scraping, 25 3/4 x 18 3/4 in., Blanton Museum of Art, The University of Texas at Austin, Bequest of John A. Robertson and gift of Carlota S. Smith in honor of Professor Richard Shiff, Effie Marie Cain Regents Chair in Art, The University of Texas at Austin, 2018, Copyright Brice Marden.