Conserving Oliver Lee Jackson’s “Untitled (Sharpeville Series)”

Conserving Oliver Lee Jackson’s “Untitled (Sharpeville Series)”

December 8, 2020 by Christian Wurst

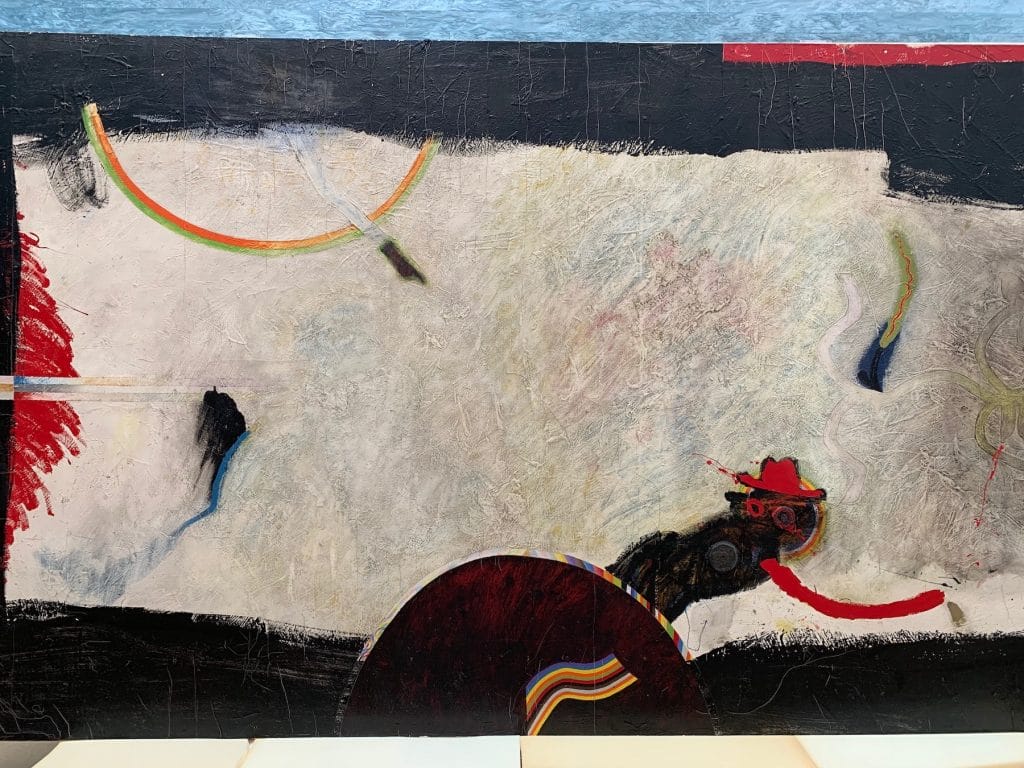

As you enter the first gallery of Expanding Abstraction: Pushing the Boundaries of Painting in the Americas, 1958–1983 titled “Emphatic Gestures,” the first painting you encounter across the room is the largest work in the show and one of the most striking. One of the newest additions to the museum’s collection and making its debut in the galleries, this work is also the latest to undergo conservation work.

In 2018, the Blanton Museum of Art received the gift offer from an art advisor representing the artist. The painting was owned by the late artist Joseph Wheelwright and his wife Susan and was housed in his former studio in Dorchester, Massachusetts. In June of that year, Carter E. Foster, Deputy Director for Curatorial Affairs, visited the studio at the invitation of Mrs. Wheelwright to assess the work. On the second floor of a very active workshop, the large painting was propped against a wall and a layer of grime and dust from years of being stored there covered the work. Despite the need of some conservation work, Carter believed it would be a major gain for the collection.

Oliver Lee Jackson was born in St. Louis, Missouri, and after studying art at Illinois Wesleyan University and the University of Iowa, he became active in his hometown as a community arts organizer. He was also involved with the Black Arts Group (BAG), a collective of musicians, dancers and theatre performers who favored a cross-disciplinary approach to their work. Since 1982, he has lived and worked in Oakland, California. In 2019, he had a solo exhibition of recent work at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C.

This painting belongs to a series that responded to the Sharpeville Massacre in South Africa, a brutal and deadly confrontation on March 21, 1960, between residents from Sharpeville township — south west of Johannesburg — and an apartheid police force using live ammunition. The community was peacefully protesting discriminatory and hated “pass laws,” ones used to restrict the movements of Black South Africans. The confrontation ended with apartheid police shooting and killing dozens of people. Sharpeville Day is now called Human Rights Day in South Africa and is acknowledged annually.

The artist had travelled to Africa in the 1960s and was influenced by the materiality of African art. As he himself describes these works:

[D]uring the late 1960s and 1970s, I was involved in a series of paintings, the “Sharpeville” series, that were very physical. They had a painted surface and an applied surface of materials that ranged in substance from cloth to glass beads to plastic to metal pieces. I needed a physicality that was palpable, very beautiful, but at the same time tough, apart from the kind of toughness that paint can give–an actual physical engagement with the same sense experience of touch.

By the time the painting arrived at the Blanton, the materiality and brushwork Jackson applied to this painting now required careful and extensive cleaning before being installed in the galleries—the artist confirmed cracks discovered in the painting were not intentional but could be addressed and repaired at a later time.

The cleaning effort occurred in two phases and was led by Anne Zanikos and Scott Jennings, of Anne Zanikos Art Conservation Studio, based in San Antonio, Texas. The first phase in September 2019 consisted of an attentive dusting using a handheld brush to remove loose dust particles. The following summer, after delays due to the pandemic and a couple of months before the opening of Expanding Abstraction, the second phase began and involved the more comprehensive process of removing built-up grime from the surface of the painting using mild, organic solvents. The cleaning took place in the Blanton’s painting storage and took two full days as the two conservators—following new Covid19 protocols—sat on opposite sides of the painting slowly removing grime using large cotton swabs.

By the end of the conservation, the painting was brought back to life. The large swaths of black and white were more dramatic and slight variations in color became more distinguishable. The beadwork and brushwork now shined under spotlight. Oliver Lee Jackson’s abstract painting addressing police brutality, racial tension, and the resilience of communities was ready for the public once again.