Austin In Depth

CHAPTER 5: Building Austin: 2015–17

Chapters

While the designs for what would eventually become Austin were not something Kelly was necessarily looking to sell, he discussed the project with numerous potential partners over the years. Kelly wanted an accessible public setting for his structure, and for it to be cared for in perpetuity. In 2012, Houston gallerist Hiram Butler began promoting the idea of realizing Kelly’s pavilion to various institutions in Houston. The project did not gain the necessary traction there, and Butler next brought the project to his alma mater, The University of Texas at Austin. Butler first discussed it with philanthropists Jeanne and Michael Klein, and Mrs. Klein took the idea to Blanton Museum of Art director Simone Wicha. Wicha immediately understood the significance of the project but also realized that building a monumental work of art on a large university campus would present a unique set of challenges. She began in-depth, exploratory conversations with the university’s then-president Bill Powers and then-provost Steve Leslie in December 2012 to garner their support and make the project a priority at the university. Because of its scale, the project would also need to be reviewed and approved by The University of Texas System’s Board of Regents. The museum had to be sure that it could fulfill these conditions while, first and foremost, realizing the work of art as the artist envisioned it. Given that the construction of Austin would mean bringing together a large team of stakeholders—from the artist to the university to the design/build team and their many subcontractors—Wicha recognized that the museum would need to navigate the project through an intrinsically complex system while acting as the artist’s advocate from design through construction.

The Blanton and Kelly began to explore a partnership in earnest in January 2013. The museum had no connection to Kelly previously, beyond owning one major painting by him, High Yellow (1960). In order to bring Kelly’s project to UT’s campus, the university needed to retain an architect of record to take Kelly’s blueprints from the 1980s (which included drawings for the building’s architectural, structural, electrical, and mechanical systems) and embark on preliminary studies to determine scope, feasibility, and estimated cost. Wicha approached the Kleins and Austin art collectors Suzanne Deal Booth and David Booth to see if they would be willing to provide initial seed money to bring on the architect, and the university hired Overland Partners to do these studies.

Another important show of commitment toward the artist and project came from the president of the university at the time, Bill Powers, who at the outset of conversations about the project committed $1 million of university funds and subsequently allowed the museum to designate the funds toward launching an endowment for the care and conservation of the work, signaling a long-term commitment to Austin. In the summer of 2013, Wicha discussed the project with longtime Blanton supporters Judy and Charles Tate, who also became major advocates. Soon after, Wicha met with Jack S. Blanton, Jr., Eddy Blanton, Elizabeth Wareing (the children of Jack S. Blanton) and their spouses and children.The Blanton family, also key supporters of the museum, stepped forward to support the project, adding to the leading gifts from the Kleins, Tates, and Booths.

Jack Shear—Kelly’s partner and president of the Kelly Foundation—made his first visit to Austin in March 2014 to further explore the partnership and view the proposed site. Shear’s steadfast support was essential to building a relationship with Kelly, and ultimately to the project’s success at the Blanton. Over the coming months, the Blanton worked to produce a gift agreement with Kelly. This agreement outlined that the museum would accession the work into its collection, oversee its long-term care, ensure that it would remain true to its original design and intent, and that the Blanton would serve as a center for the study of Kelly’s work. The gift agreement was finalized in January 2015, enabling Powers and Wicha to take the project to the Board of Regents for formal approval, seeking their acceptance of the gift and consent to move forward. Shortly thereafter, the Blanton officially launched a $23 million campaign for Austin, having already secured half of the necessary funds to construct, fabricate, and build an endowment for the operation, care, and conservation of the work through a silent phase of fundraising. The campaign was completed in December 2017 and ultimately brought together Blanton and Kelly supporters from across Texas and the United States.

Since Kelly had long worked out the main design concepts and the art for Austin, moving forward now meant updating the structure for its new setting and role as a public building. In order to ensure that Austin’s realization accurately reflected the artist’s vision while meeting necessary building requirements, over a period of six months, from June until December 2015, the Blanton managed a systematic review and approval process with Kelly and Shear. As Kelly was unable to visit the proposed site during the design development phase, numerous mockups, models, material samples, drawings, and renderings were sent to his studio for his review and approval. Shear made regular visits to Austin to view on-site mockups during design development and later the construction phase. He and Wicha also traveled to Carlson Arts LLC in California, where the marble panels and redwood totem were being produced; Franz Mayer of Munich, where the colored glass was fabricated; and to Alicante, Spain, where the limestone for the façade was culled.

When designed for California, Kelly’s building was to have thinner walls of cast concrete and, at least in its earliest incarnations, no lighting or climate systems. In Texas, Austin would be in a prominent location with security, climate control, lighting, and building codes all a necessity. This produced some of the greatest design challenges: how to make the systems that normally support a building essentially “disappear” within the structure so that they were not seen. Working closely with their mechanical engineers, the architect and the builders, Linbeck Group, were able to hide the climate control system inside the walls and above the light raft, along with other necessary mechanical elements. While working through the engineering of this, Kelly worried at one point that the walls had grown too thick and feared that having the 24-inch-thick walls would limit the light transmitted through the windows. After some further engineering, the thickness of the window walls was ultimately reduced to 16 inches. Similarly, Kelly wished for the reveal at the base of the walls to be less visually prominent than what was initially proposed to meet airflow requirements; again, the design/build team was able to address the artist’s request through some clever redesign.

While updating the concept for Texas, Kelly realized that he wanted to make a few other adjustments: first, he wanted the “nave” to be slightly longer than originally conceived, to make more space for the art inside and to give the sense of a vestibule. It was thus lengthened from 25 to just over 33 feet. The height of the building also had to be adjusted to accommodate thicker walls; it was raised from 25 to just over 28 feet. This helped make an improvement on the front facade, whose grid of nine squares fit very differently into the arch than the other two windows. Because of their round shape, both circular stained-glass compositions on the west and east facades fit perfectly into the building’s arches, whose springing point bisected each window symmetrically. Raising the building’s height meant the front window would now similarly have this symmetry with the arch, as well as more space around the window at the top, which the artist considered an improvement. [figure 45]

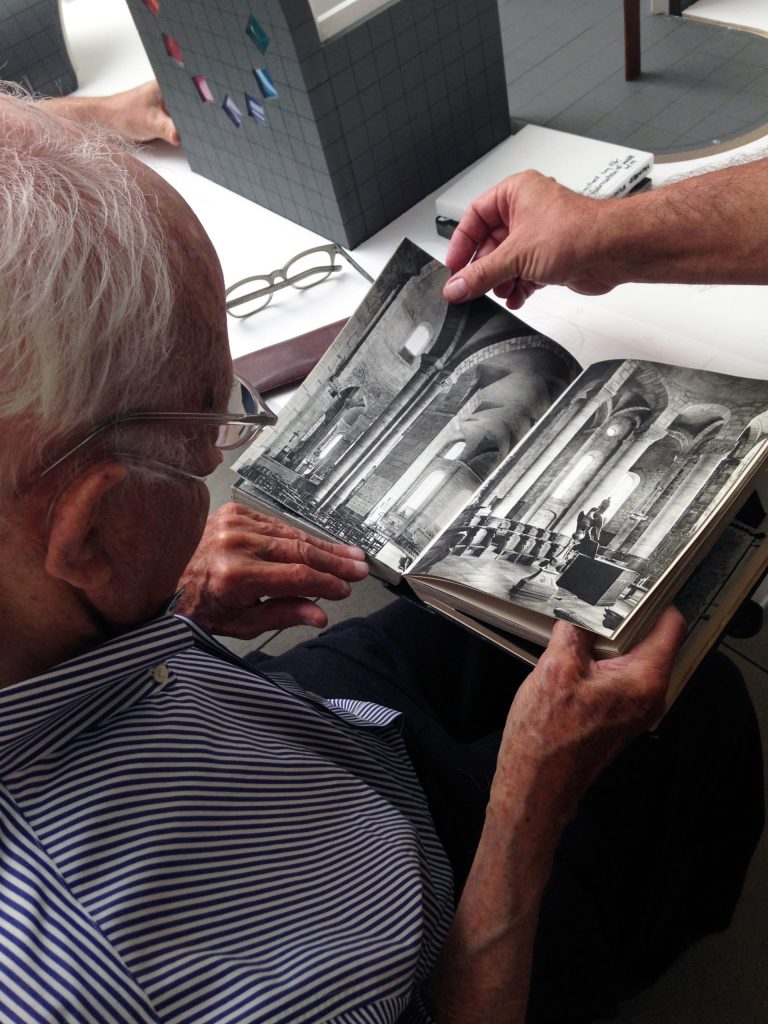

Perhaps the most dramatic change from the first incarnation of Austin as the Cramer pavilion to its executed design is the use of stone on the exterior. Kelly had originally wanted a Mediterranean-style, white-washed, possibly stuccoed, surface when the building was designed for California, but there were concerns that this would not hold up in the Texas climate. Kelly’s original vision for the stuccoed facade is reflected in the late model his studio assistant Nick Walters made in 2014 [figure 46]. In the early phases of conversation about Austin at the Blanton, a fairly dark stone with a regularized grid was proposed and a model was made of this as well [figure 47], but it was quite far from the aesthetic that had originally inspired Kelly—Romanesque architecture. So the artist then went back to his books, looking at photographs of some of the monuments he had seen in France [figure 48]. One of the qualities he admired in old stonework was its irregularity, its hand-laid and, to some degree, random quality based on the variety of individual stones available and laid by multiple masons over decades and even centuries. The material he eventually selected was a light gray limestone from the Bateig quarry in Alicante, Spain.

To achieve the look and feel Kelly wanted, the architects designed nine different widths of stone and three different heights. A computer program determined random sequencing for each stone so that every piece has a unique placement in the overall coursing. Each stone had to be individually cut and precisely finished in order to fit together and to the framework that holds the stones in place. The cutting was especially tricky for the curved surfaces of the barrel vaults. It was carried out at the quarry, with the hundreds of cut pieces shipped to Austin for exterior placement (there are 1,569 pieces altogether).

The Blanton broke ground on Austin and began excavation of the site on October 31, 2015. As the sitework progressed, design development continued. Wicha called Kelly in late December 2015, just weeks before he passed away, to confirm the final selections and let him know that the process was moving forward and that all of his decisions had been fully documented. His design decisions were recorded in a 150-page “Artist Approval” book that served as the foundation for realizing the building when construction began in earnest in early 2016. The final building remained very true to this document, save for some minor substitutions where there were supply issues. Austin opened to the public on February 18, 2018, unveiled in a public dedication ceremony delivered by Austin Mayor Steve Adler, UT President Greg Fenves, Shear, and Wicha.

IMAGE CREDIT: Ellsworth Kelly looking at architectural references, New York, July 2014. Photo courtesy Ellsworth Kelly Studio.